Mass and Gravitation

Applications of Mass and Gravity

Many enigmas can be clarified by replacing the concept of "mass" with that of a "closed volume" — a volume that inherently contains mass.

In the previous chapters, we have shown that the curvature of spacetime is caused by closed volumes rather than mass itself. To illustrate this concept, we used a simple example: when a marble is dropped into a glass filled to the brim with water, it is the marble’s volume — not its mass — that causes the water to overflow. A similar phenomenon occurs with spacetime.

We have concluded that both mass and gravitation result from the pressure exerted by spacetime curvature on the surface of closed volumes of objects.

To conclude this first part, we will explore several enigmas involving spacetime, mass, and gravitation. These propositions, however, remain theoretical in nature and require experimental validation to be confirmed.

Mass of Relativistic Particles

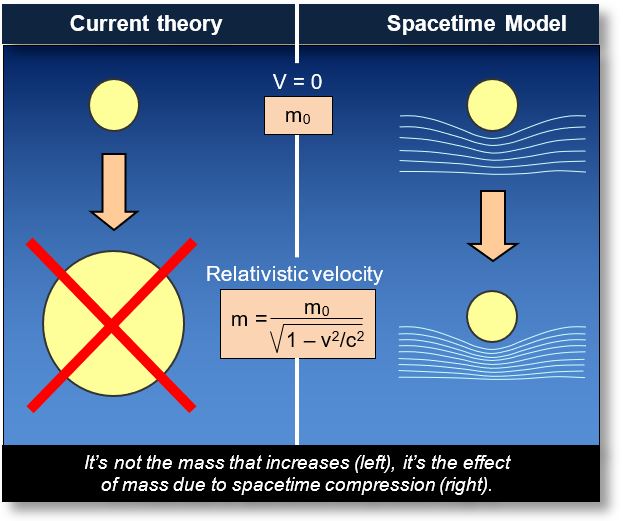

Relativistic particles are elementary particles — such as electrons or protons — that move at speeds close to the speed of light (approximately 300,000 km/s). At such velocities, their mass appears to increase.

For example, if a car has a mass of 800 kg at rest, its mass would be perceived as several thousand tons when moving at relativistic speed. This phenomenon was demonstrated by Einstein in his theory of special relativity.

At relativistic speeds, spacetime becomes compressed, as illustrated in the figure on the next page. This effect is somewhat analogous to the aerodynamic drag experienced by a vehicle at high speed, represented by the well-known formula kv2, which resists motion. Overcoming this resistance requires additional energy, creating the perception — by an external observer — of increased mass.

A similar phenomenon occurs in quantum mechanics: particles are slowed down by spacetime compression, which gives rise to the illusion of increased mass.

Note: It may be objected that the method described here pertains to the spacetime of General Relativity (GR), rather than that of Special Relativity (SR). This is a valid point; however, GR is an extension of SR. This relationship is evident in the Einstein Field Equations or "EFEs" (see Appendix A5). In GR, the Minkowski space of SR is first generalized to a Gaussian space, and ultimately to a Riemannian manifold. At relativistic speeds, geodesics become more constrained. The relativistic equation presented here can also be derived using the length contraction principle from SR. Note that a very simple explanation of Special Relativity (SR) is provided in our book published on Amazon (see the bottom of the page)

Contraction–Expansion of Spacetime

Einstein developed two theories of relativity:

- Special Relativity (SR) This theory describes the relationship between the four-dimensional spacetime coordinates (x, y, z, t) as experienced by an observer and those experienced internally by an object in motion.

- General Relativity (GR) GR explains the contraction and expansion of spacetime in the vicinity of a massive object — conceptualized here as a closed volume. Although GR and SR share foundational principles, the phenomena they describe differ significantly.

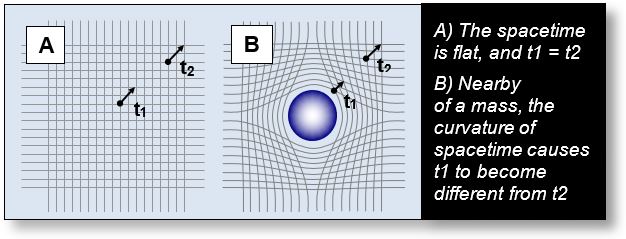

- Fig. A: Far from any closed volume (or "mass volume"), spacetime remains flat. Geodesics are straight lines, and both space and time are uniform: t1=t2.

- Fig. B: A closed volume induces curvature in spacetime. As a result, geodesics — and thus time intervals and spatial distances — are altered. Time t1 becomes different from time t2. The Schwarzschild solution, a specific case of the Einstein Field Equations (EFEs), allows us to quantify this distortion for objects with spherical symmetry.

Note: In Appendix A6, we present a reformulated version of the Schwarzschild metric, condensed into just two pages, compared to the original 33-page derivation of the EFEs. This constitutes further confirmation that the Spacetime Model is the theoretical framework to follow moving forward.

The Twin Paradox

The "twin paradox" is a well-known thought experiment in relativity. It involves sending one twin into space while the other remains on Earth.

This scenario reflects the same phenomenon illustrated in Figure B above. The twin who stays on Earth experiences a time interval 𝑡1, while the twin who travels through space experiences a different time interval 𝑡2. Upon returning to Earth, the traveling twin will have aged differently from his sibling who remained on Earth.

Note: It should be noted, however, that in most realistic cases, the time difference is only a few nanoseconds — barely perceptible.

Deflection of Light

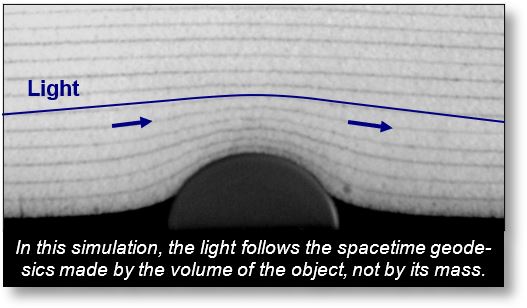

In 1919, Arthur Eddington confirmed Einstein’s theory of general relativity during a total solar eclipse. The results were conclusive: starlight passing near the Sun was deflected by approximately 2 arcseconds. Why does this happen?

As previously discussed, any closed volume naturally curves spacetime. Einstein proposed that spacetime possesses elastic properties, which can be visualized through analogies. In the experiment below, we simulate spacetime using foam to illustrate this concept. As shown, light follows the geodesics — curved paths — of spacetime, which are represented by the contours drawn on the foam.

Note 1: It should be emphasized that the curvature is convex relative to the closed volume, contrary to the concave representations often found in contemporary physics diagrams. Von Laue also supported this view in 1927 (see Appendix A4).

Note 2: In this experiment, as shown in the figure, it is the volume of the cylinder — not its mass — that curves the foam. This volume qualifies as a "closed volume" because the foam cannot penetrate the interior of the cylinder.

Note 3: The inter-geodetic space can be measured directly on the chart above. The measured distances match precisely — within the limits of experimental accuracy — the values predicted by the Schwarzschild metric. This is a real photograph, not a simulation, and therefore cannot be manipulated. It provides empirical support for the Spacetime Model, as the experiment was based on closed volumes rather than mass. The material of the central cylinder — whether wood or lead — is irrelevant. Full details of the experiment are provided in Appendix A6.

Note 4 (for physicists): The exact structure of spacetime remains unknown, but it is undoubtedly more complex than it appears. Some arguments support the idea of a "quantified continuum" (see Part 4), which falls within the domain of rheology. Clearly, spacetime is not a solid body, but it may exhibit rheological behavior. The magnitude of spacetime curvature is extremely small: Δr/R = 1.4166 x 10-39 for a proton. This minuscule value implies that, regardless of the function involved, we are operating within a linear regime of the overall process, consistent with the Schwarzschild metric.

Understanding E = mc2

How does matter become energy?

Einstein’s famous equation, E = mc², shows that mass can be converted into energy by multiplying it by the square of the speed of light (≈ 3x108m/s). This principle has been experimentally confirmed many times since 1905.

Yet the underlying mechanism remains conceptually obscure. It becomes clearer if we replace the notion of “mass” with that of a closed volume, as proposed in our formulation E = mc2 (see Appendix A2).

Imagine immersing a balloon in water (Fig. A). If it bursts (Fig. B), a depression and surface turbulence appear. Similarly, when a closed volume collapses or vanishes, it generates waves in spacetime.

This is the principle behind the atomic bomb: the excess mass of uranium-235 or plutonium-239 forms a closed volume. Its sudden disappearance creates a spacetime “tsunami” of radiation — X-rays, gamma rays, UV, etc.

This phenomenon is intuitive when viewed through closed volumes, but remains puzzling when framed in terms of mass. Einstein demonstrated the effect, but never fully explained its foundational cause.

Expansion of the Universe

How can we explain the expansion of the universe by Riess, Perlmut¬ter, and Schmidt (Nobel prize 2011) with a non-uniform expansion rate?

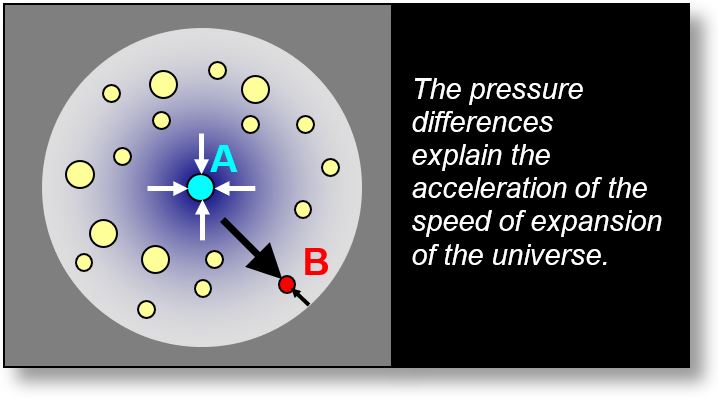

The figure below illustrates a distribution of galaxies. The blue galaxy (A), located at the center of the universe, experiences equipotential spacetime pressure from all directions (white arrows). In contrast, the red galaxy (B), positioned at the periphery, is subjected to strong inward pressure from the center (large black arrow), while the outward pressure is minimal due to the absence of surrounding galaxies (small black arrow).

As a result, central galaxies remain stationary, while peripheral galaxies are pushed outward. This pressure imbalance leads to an expansion of the universe, but one that is non-uniform and constantly evolving.

Note: This behavior was predicted by the Spacetime Model in 2006. As of 2025, researchers from Christchurch, New Zealand, have published findings that confirm this prediction (see Appendix A17).

Filaments of Galaxies

Why do galaxies cluster along filaments?

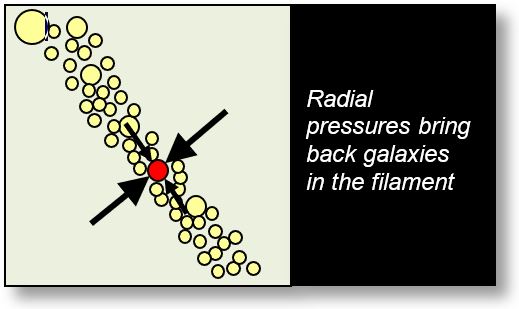

The red galaxy is subject to two distinct types of pressure:

- Axial pressure: exerted along the filament’s axis. Galaxies located within the axis (shown in beige) absorb part of the global spacetime pressure of the universe.

- Radial pressure: stronger and originating from all surrounding galaxies across the universe.

If a galaxy attempts to move away from the filament, the external radial pressure naturally redirects it back toward the filament.

Note: This is a proposed interpretation — not a definitive explanation.

Mass Excess – Nuclear Fission

Mass excess refers to the difference between an atom’s actual mass and its mass number A, which corresponds to the total number of nucleons (protons + neutrons) in the nucleus.

For example, consider a chemical element X with a mass number of 19, composed of 10 protons and 9 neutrons. If its actual atomic mass is 19.3 atomic mass units (u), the mass excess is: 19.3 − 19 = 0.3 u.

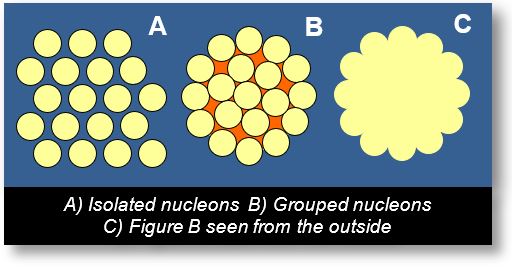

The figure below illustrates how individual nucleons, when grouped into a nucleus, can result in a measurable mass excess.

- Fig. A: The nucleons are isolated. Their total mass is calculated by multiplying the mass of a single nucleon by 19, since there are 19 nucleons.

- Fig. B: The 19 nucleons are grouped into a nucleus. A portion of spacetime — represented in orange — is trapped within the nucleus.

- Fig. C: From the outside, the nucleus appears compact and sealed. The orange region becomes invisible, having been confined. The nucleus thus behaves as a hermetic volume, and its mass effect is greater than in Fig. A due to the imprisoned spacetime.

This excess mass corresponds to the trapped orange region. If the nucleus is broken apart, this confined spacetime is released and converted into energy.

Notes:

1 - The nucleus shown here is imaginary and not the K-19.

2 - Significant mass excess is primarily found in heavy nuclei.

3 - For further details, refer to the Bethe–Weizsäcker formula (see further on this site)

4 - Certain halo nuclei, such as lithium-11 (Li-11), may present anomalies, but these light nuclei are not relevant to nuclear fission.

5 - Mass excess is more typical in heavy nuclei like uranium-235.

6 - This 2D diagram should be interpreted in four dimensions for full conceptual accuracy.

Mass Defect – Nuclear Fusion

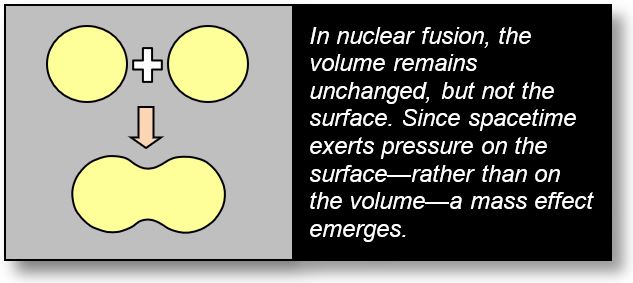

Nuclear fusion is the process of merging light atomic nuclei to form a heavier one. It’s the principle behind experimental reactors like ITER and NIF.

Fusion requires extremely high temperatures, achieved either through magnetic confinement (TOKAMAK) or, more recently, high-power lasers.

During fusion, protons and neutrons rearrange, altering the volume and surface of the resulting nucleus. As illustrated in the simplified figure, the resulting nucleus has a smaller surface area than the two initial nuclei. This reduction increases the mass effect, and the difference — linked to the surface of closed volumes — is released as energy.

Apparent Mass Increase of a Particle in a Crystal

Why does a particle’s mass seem to increase when moving through a crystal? The explanation is surprisingly simple.

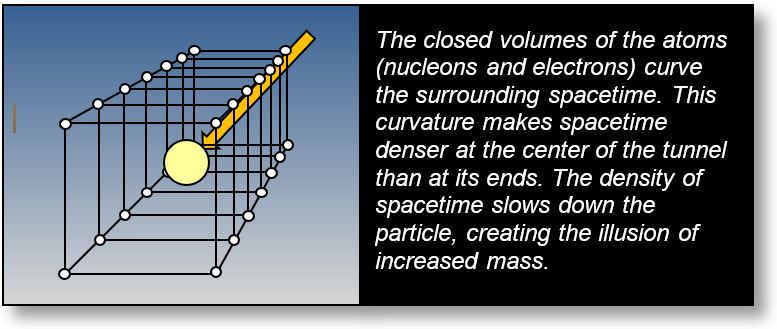

In crystals, atoms are arranged in a regular lattice, forming tunnel-like paths. As a particle travels through one of these tunnels, the closed volumes of the atoms (nucleons and electrons) curve the surrounding spacetime. This curvature makes spacetime denser at the center of the tunnel than at its ends.

To illustrate: imagine a high-speed train entering a tunnel. Air compresses inside, increasing resistance and slowing the train. From a distance, it may appear as if the train’s mass has increased — though it hasn’t. The denser medium is simply harder to move through.

Similarly, in a crystal, the particle’s rest mass remains unchanged, but the denser spacetime slows its motion, creating the illusion of increased mass.

Enigma of Black Hole Mass — Radius

We conclude this section with this final example that challenges the entire scientific community of astrophysicists. No physicist really understands what is going on. Yet, the solution to this enigma is surprisingly simple.

This example once again confirms that our explanation of mass and gravitation is the right path to follow.

Black holes remain one of astrophysics’ great mysteries. In everyday experience, mass is proportional to volume — double the mass, double the size, assuming constant density. But black holes defy this logic: their mass is not proportional to volume, but to radius, which seems counterintuitive.

Explanation:

- The mass effect is proportional to the volume V,

- ...since greater volume increases spacetime curvature and pressure.

- It is also inversely proportional to the surface area S,

- ...because spacetime pressure acts on the surface — smaller surface means stronger pressure (like a stiletto heel).

- The mass effect is therefore proportional to V/S.

- The volume V is expressed in R3, where R is the radius,

- ...and the surface S is expressed in R2.

- That gives V/S = R3/R2 = R.

Thus, the mass of a black hole scales with its radius, not its volume.

This result supports the Spacetime Model, offering a fresh perspective on mass and gravitation in astrophysic.

Summary of Part 1

By replacing the concept of "mass" with that of a "closed volume" (or "mass volume," which amounts to the same), the enigmas surrounding mass and gravitation can be resolved with remarkable simplicity. There is no need for pages upon pages of complex mathematics — just a bit of common sense suffices. The core principle can be summarized in a few concise lines:

- A closed volume curves spacetime.

- This curvature generates pressure on the surface of the volume.

- These pressures restrict the volume’s freedom of movement.

- This phenomenon is what we call "mass" (see Fig. A).

- Due to these pressures, closed volumes tend to move closer to one another.

- This interaction is what we call "gravitation" (see Fig. B).

- Ultimately, both mass and gravitation arise from the pressure exerted by spacetime on the surface of closed volumes.

Understanding such a phenomenon does not require advanced scientific training.

This first part of the Spacetime Model is now coming to a close.

As demonstrated, mass and gravitation can be unified within a single, coherent theory of surprising simplicity.