Spacetime

Interactions and Fields in Spacetime

Electromagnetic radiation (EM) is described with remarkable mathematical precision, yet no one can truly explain why the speed of light, denoted by c, remains constant at 299,792 km/s — or, more simply, 300,000 km/s.

The invariance of "c" is a fascinating phenomenon. More importantly, it opens a pathway toward solving the deeper mystery of particle structure.

This section therefore pursues two main objectives:

- To understand the nature of electromagnetic waves

- And, through the principle of duality, to deduce the nature of particles

In other words, grasping the concept of wave–particle duality will naturally guide us toward uncovering the internal structure of particles.

EM Waves in Spacetime

Electromagnetic waves (EM) are movements within spacetime. Their propagation is analogous to the ripples created when a stone falls into water.

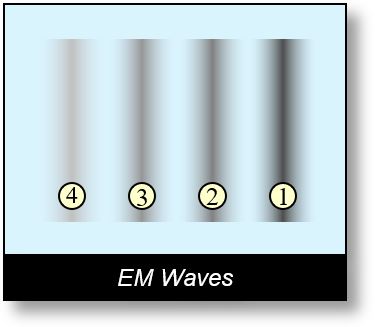

The figure below illustrates a simplified sine wave traveling from left to right. Period 1 represents the primary cycle, while periods 2, 3, 4… are secondary cycles.

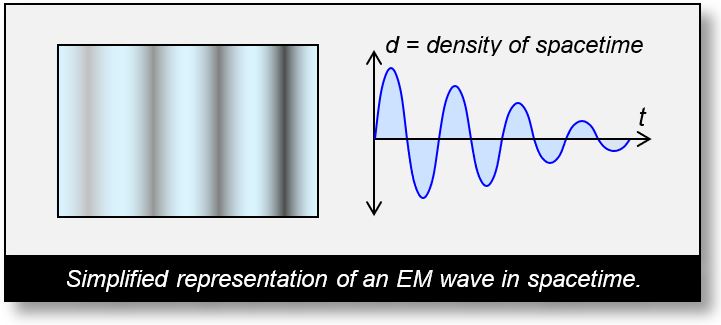

The figure below presents a mathematical representation of a sine wave. Such a curve can model any physical phenomenon. In this context, it describes variations in the density of spacetime.

Mathematical Formalization

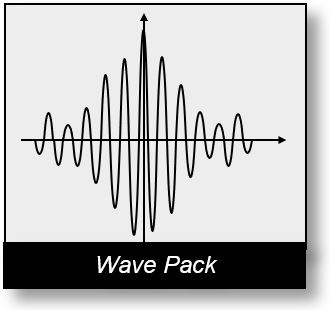

From a mathematical perspective, a set of elementary waves is referred to as a wave packet. In quantum mechanics, a wave packet represents the probability of a particle being in a specific state, as introduced by Max Born. We will revisit this concept later.

Einstein opposed this probabilistic interpretation of the universe. He believed that the universe was entirely rational and deterministic, not governed by chance.

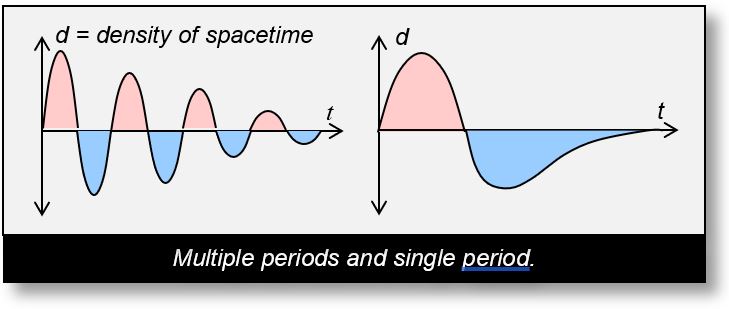

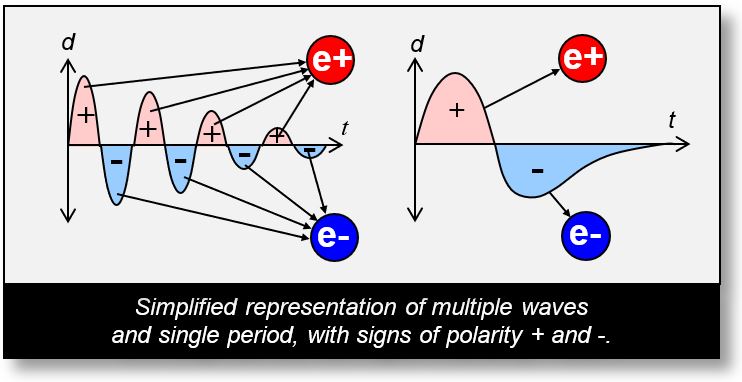

The figure below illustrates a simple sinusoidal curve: multiple periods are shown on the left, while a single period is displayed on the right.

Polarities in Spacetime

To illustrate, consider acoustic waves: sound arises from alternating pressure zones in the air, caused by speaker vibrations. A tiny air volume (e.g., 1 cm³) may be denser or less dense than average due to these oscillations.

Electromagnetic (EM) waves create similar variations in spacetime. Its density fluctuates—sometimes higher, sometimes lower—and is not uniform across the universe. This prediction, namely the density of spacetime is not uniform at each point of the universe, has been validated by Physicists. See Appendix A11 of the book.

In the figure below, '+' marks regions of high spacetime density, '-' marks low-density zones, and the neutral line (t-axis with ordinate 0) represents areas without wave influence.

In the end, we will assign the name ‘Electron’ (e⁻) to the negative parts of the wave, and ‘Positron’ (e⁺) to the positive parts. Although this allocation may seem arbitrary at first, we will later see that it is fully justified by experimental evidence.

Note: For now, this topic has been deliberately simplified for educational purposes. The following chapters will provide a more complete explanation.

Limits of Einstein’s Spacetime

The spacetime described in Part 1 has helped us understand mass, gravity, and solve many physical problems. It corresponds to the global spacetime of the universe, formulated by Einstein in his field equations (EFEs) in 1916.

According to academic physics, light travels at 300,000 km/s in a vacuum. While this is accurate, the explanation remains incomplete: Einstein’s spacetime is currently the only framework used to describe the vacuum, yet it does not account for the polarity (‘+’ and ‘–’) of physical entities. This is problematic, as waves and particles often exhibit polarity.

So, could there be a second spacetime that incorporates polarity? If not, what medium supports the propagation of electromagnetic waves? Einstein’s gravitational spacetime cannot fulfill this role, since it ignores polarity altogether.

In summary, the EFEs do not include polarity. The appendix of the book provides a detailed overview of EFEs equations, allowing readers to verify this themselves. The key question now becomes:

What is the nature of this second spacetime that allows polarized components — such as particles — to propagate?