Particles Annihilation

Annihilation Processes in Spacetime Fields

In this chapter, we examine a scenario that involves the forces of spacetime and the wave–corpuscle duality described earlier. We will explore what happens when two regions of spacetime with opposite densities come into contact.

The nature of this interaction remains unknown at this stage, but we will attempt to associate it with a phenomenon familiar to physicists.

Creation of an e-– e+ Pair

We are going to examine a physical phenomenon triggered by an electromagnetic (EM) wave. The outcome is not yet known.

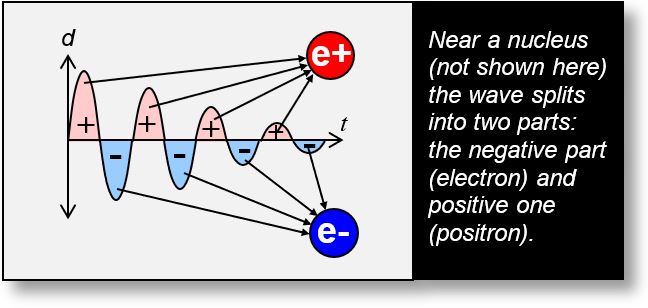

The figure below shows an electromagnetic wave composed of alternating positive and negative zones. In spacetime, the positive zones (shown in pink) correspond to regions of high density, while the negative zones (in blue) represent regions of low density.

Now, suppose this wave passes near the nucleus of an atom, which is positively charged.

The negative parts of the wave will be attracted to the nucleus, while the positive parts will be repelled. As a result, the wave splits into two distinct regions with opposite polarities, labeled e⁺ and e⁻ in the figure above. As noted earlier, we refer to the positive region as a positron (e⁺), and the negative region as an electron (e⁻). Thus, a positron–electron pair is formed.

Note: For this phenomenon to occur, the energy of the incident wave must be at least 1.022 MeV/c2. This places the wave produced in the category of gamma radiation.

Annihilation of an e-– e+ Pair

Let us now examine what happens when the positron created earlier encounters an electron. It is important to note that electrons and positrons may originate from different sources, such as β⁻ or β⁺ radioactivity.

These two entities — the positron (e⁺) and the electron (e⁻) — will annihilate each other due to their opposite polarities. This annihilation generates turbulence in the surrounding spacetime. Similar phenomena occur on Earth: when a mass of hot air meets a mass of cold air, winds and thunderstorms often result.

In spacetime, the behavior is analogous. When two regions of opposite polarity — such as a positron and an electron — collide, they annihilate each other, thereby disturbing the local environment.

Recapitulation of Annihilations

In the first phase below, a gamma ray produces an electron and a positron. In the second phase, the electron and positron meet and annihilate each other. Here is the complete process:

1/ Creation (see the preceding figure)

- A gamma ray passes near a charged element, such as the nucleus of an atom.

- The positively charged nucleus attracts the negative regions of the wave.

- The positive regions are repelled by the nucleus.

- As a result, the wave splits into two distinct parts: one negative and one positive.

- The negative part is called an electron (e⁻).

- The positive part is called a positron (e⁺).

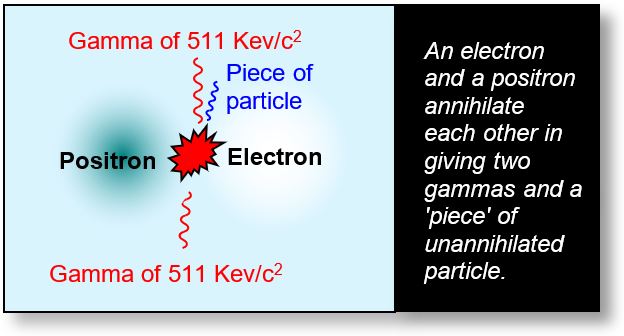

2/ Annihilation (see the figure below)

- From the negative and positive regions of the incident wave, we obtain an electron and a positron.

- When they come into contact, the electron and positron annihilate each other due to their opposite polarities.

- This annihilation causes intense disturbances in spacetime, resulting in high-energy electromagnetic waves known as gamma rays.

- The positron and electron disappear. This disappearance is also observed during experiments.

- Ultimately, the electron and positron are transformed back into gamma rays, consistent with the wave–corpuscle duality.

- We have also explained how a closed volume can be transformed into waves, and vice versa (see the webpage "Applications" of Part 1).

In this explanation, the starting point is an electromagnetic wave, and the end point is two electromagnetic waves emitted into spacetime. The cycle is complete: an EM wave becomes an EM wave once again.

Electron vs. Positron

Imagine that the electron (in region B) is 0.1% more higher than the positron in the corresponding region. What would happen?

It’s simple: the surplus 0.1% will not be annihilated.

A small portion of the incident wave will be emitted in a direction that conserves kinetic momentum. This residual particle will necessarily be a fragment of either the electron or the positron. Physicists refer to it using the terms neutrino and antineutrino.

Creation of the Neutrino–Antineutrino

Neutrinos and their antiparticles, antineutrinos, are extremely difficult to detect because they carry no electric charge. Only one neutrino out of ten billion passing through Earth will interact with matter. This is why they are often referred to as "ghost particles".

The e-– e+ annihilation scenario described above can lead to the creation of an antineutrino. Here's what happens:

- If the volumes of the positron and electron differ slightly, a small portion of the larger particle will remain unannihilated. This residual fragment is either a neutrino or an antineutrino.

- Keep in mind that the closed volumes of the electron and positron may not be perfectly identical. There are several reasons why they might differ slightly (less than 1 part per million).

- According to current estimates, neutrinos and antineutrinos have an infinitesimal mass and no electric charge. However, the Spacetime Model challenges this view. Logically, mass and charge are inseparable: zero mass implies zero charge, and non-zero mass implies non-zero charge.

- It is possible that a minimum threshold—or quantum—is not reached. This explanation is detailed in Part 4.

- Thus, we can conclude that:

It is highly probable that the neutrino and antineutrino originate from a difference of volume in closed volumes -i.e. mass- between the electron and the positron.

For physicists: In the Spacetime Model, neutrinos and antineutrinos must theoretically have a spin of ½, since they originate from either the electron or the positron. This perspective aligns with experimental observations of neutrino behavior.

The Physicists’ Point of View

Physicists will likely challenge this explanation of the neutrino’s role in e⁺e⁻ annihilation, particularly regarding spin. Two key questions arise during this interaction:

- Origin of the Neutrino: Academic physics generally does not consider neutrinos to originate from electrons, positrons, or any other particles involved in annihilation. Let us recall the foundational principle of physics: nothing is lost, nothing is created. Claiming that the neutrino “comes from nowhere” would be considered heretical. Therefore, before proceeding further, it is essential to investigate the neutrino’s origin.

- Spin Extrapolation. Spin has been used in physics for over a century, yet its true nature remains elusive. It is treated as a quantum value — meaning, in practical terms, "...we do not know...". In the 1920s, spin was applied with great interest to atomic phenomena such as the Zeeman effect and energy levels. At that time, the structure of the nucleus was still unknown: the proton was discovered in 1919, and the neutron in 1932. Later, spin was extended to nuclear physics. However, extrapolating spin behavior from atoms to nuclei is questionable. Just because spin works well in atomic models does not guarantee it behaves similarly within the nucleus.

Extending the poorly understood concept of spin from atomic orbitals to nuclear structure is highly risky.

For Physicists: The accuracy of neutrino measurements is: |me+ - me-|/me < 8.10-9, with a confidence of 90%. Until 1998, neutrinos were considered to have zero mass. The Super-Kamioka experiment (see photo) has put an end to this misconception. Their mass is now estimated to be less than 30 eV/mc2, which is very low. A more detailed explanation of the neutrino is given further.

Summary Concerning Annihilations

This webpage explores both the creation and annihilation of particles. The complete process is as follows:

- A high-energy electromagnetic (EM) wave passes near an atomic nucleus.

- The positively charged nucleus attracts the negative regions of the wave, while repelling the positive ones.

- As a result, the wave splits into two distinct parts: one positive and one negative.

- This leads to the formation of a positron (e⁺) and an electron (e⁻)

- When the positron encounters an electron, annihilation occurs.

- This interaction causes a disturbance in spacetime.

- These disturbances manifest as two high-energy EM waves — gamma rays.

- If the electron and positron differ slightly in volume, a small portion remains unannihilated.

- This residual fragment is referred to as a neutrino or antineutrino.

- Thus, spacetime returns to its original state.

This scenario is supported by experimental observations conducted routinely in physics laboratories.