Nature of Particles

Understanding Particle

Behavior in Spacetime

We know of more than a hundred elementary particles. Among the most common are the electron and its antiparticle, the positron. Later, we will demonstrate that the electron and positron are the two fundamental particles of the universe.

For this reason, we will continue our investigation into the constitution of matter and particles by focusing on electrons and positrons. The aim of this chapter is to synthesize our previous deductions.

Particle Composition: Five Distinct Approaches

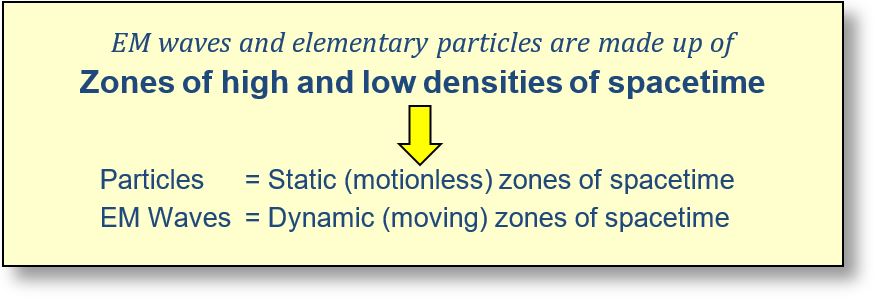

The following inferences, drawn through , consistently lead to the same conclusion. Although it may seem surprising, the elementary particles that constitute everyday objects are static zones of spacetime, whereas waves represent dynamic zones. Here’s why:

1 - First Principle of Duality

This principle offers a complete explanation of the wave–particle duality enigma. It asserts that particles and waves must share the same underlying constitution; otherwise, the duality remains an unsolvable paradox. We know that the primary medium enabling waves to propagate at a constant speed is spacetime — there is no alternative. By deduction, particles must also be composed of spacetime, since: primary medium (spacetime) → waves → corpuscles.

2 - Electron–Positron Production

When a gamma photon passes near a nucleus or a charged particle, it can split into an electron–positron pair, provided its energy is sufficient. The figure on the next page shows the electron (in blue) and the positron (in red). Both emerge from the wave — that is, from spacetime. Therefore, the electron and the positron are composed of spacetime.

3 - Electron–Positron Annihilation

In the previous chapter, we saw that electron–positron annihilation (e⁺e⁻) is a direct transformation of spacetime in its particle form into spacetime in its wave form. This experiment demonstrates that waves and particles are equivalent expressions of spacetime, thereby confirming the principles of wave–corpuscle duality.

4 - De Broglie’s Waves

In 1924, Louis de Broglie proposed that any particle could be associated with a wave similar to electromagnetic (EM) waves. This hypothesis was experimentally confirmed by Davisson and Germer in 1927. Therefore:

- Any particle can transform into a wave, like EM waves (de Broglie, Davisson and Germer).

- EM waves are vibrations of spacetime.

- Duality requires that particles share the same nature as waves.

By combining these three points, it becomes evident that EM waves, de Broglie waves, and particles are all composed of spacetime.

5 - The Coulomb Force

The electric force known as the Coulomb force was named after the physicist who discovered it. Let us revisit the annihilation scenario from the previous chapter.

What is the force that brings the two zones, e⁺ and e⁻, together until they annihilate? Given that only four fundamental forces exist in the universe, we are left with four possibilities:

- Gravitation? The scenario involves two zones polarized as '+' and '−'. However, gravity does not account for polarity. Therefore, this unknown force cannot be gravitational.

- Strong Nuclear Force? This force ensures the cohesion of quarks within the nucleus but does not involve polarity. Hence, it cannot be the strong nuclear force either.

- Electroweak Force? The electroweak interaction acts only on specific particles such as the Z⁰, W⁺, and W⁻ bosons. This force does not apply here.

- Electromagnetic Force? By elimination, we are left with the electromagnetic (EM) force. Indeed, the attractive force between two oppositely charged particles is the Coulomb force. Furthermore, this unknown force could be electromagnetic in nature, since both zones — e+ and e- — originate from EM waves.

Note: The electromagnetic force (EM) has two components, one electric, the Coulomb component that is discussed here, and the other magnetic. We will see this magnetic component in Part 4.

Since the Coulomb force acts only on charged particles, we can infer that both zones, e⁺ and e⁻, are composed of charged particles. And because these zones are fragments of an EM wave—or spacetime itself—we naturally deduce that the particles involved, the electron and the positron, are also made of spacetime.

Einstein’s View

Let us consider this remark by Einstein, which tends to support our conclusions: “Matter cannot exist without spacetime.” While this statement does not explicitly say “Matter is made of spacetime,” it nonetheless aligns with the same conceptual framework.

The Laws of the Universe

Einstein took interest in Kaluza’s theories on multidimensional universes, but ultimately returned to a model with four dimensions. For Einstein, the entire universe must be described using only four variables: x, y, z, and t. Consequently, the four fundamental forces must also be expressible within this 4D framework:

- Gravitation: Part 1 demonstrated that gravity can be expressed in four dimensions: x, y, z, and t.

- Strong Nuclear Force: As explained in Part 5, the strong nuclear force is essentially a classical Hooke’s force, known since the 1800s. It too operates within four dimensions.

- Electroweak Force: This force is examined later and, similarly, is expressed in four dimensions.

- Electromagnetic Force: The EM force is also defined using the four variables: x, y, z, t.

These forces are intrinsically linked to particles and waves. Therefore, a four-dimensional spacetime — consistent with Einstein’s framework — is entirely sufficient to explain particles, waves, and forces. This unified view accounts for all the laws of the universe.

Summary: Waves and Particles,

A Spacetime Perspective

All experiments conducted over the past century—by Davisson, Germer, and others—point in the same direction: waves and particles are both made of spacetime. In both cases, we are dealing with the same fundamental medium. The only distinction lies in the nature of their motion:

- Static spacetime (motionless) corresponds to particles.

- Dynamic spacetime (in motion) corresponds to waves.

It was shown on the “Wave–Corpuscle Duality” page that corpuscular water may be transformed into aquatic waves. The same principle applies to spacetime: waves can transform into elementary particles, which are corpuscular modules of spacetime—and vice versa.