Fields in Spacetime

Fields in Spacetime: A Reality?

Until now, for pedagogical reasons, we have deliberately maintained a certain vagueness in the definition of spacetime. In this chapter, we aim to clarify that ambiguity.

Field: A field is the set of values that a physical quantity assumes at every point in space. It is typically represented by a vector. A field cannot exist independently of the physical object that generates it. For example, an electron produces an electric field. If the electron disappears, the field vanishes as well.

Spacetime: Spacetime serves as the substrate for fields. Even in the absence of particles — such as the aforementioned electron — spacetime continues to exist. It is a physical entity. Spacetime constitutes the fundamental structure of the universe

History of Fields in Spacetime

In the 1920s, Einstein was captivated by Theodor Kaluza’s ideas about spacetime, and regarded him as a genius. Kaluza, who reportedly spoke 17 languages, had made a remarkable contribution by extending Maxwell’s equations — equations that Einstein himself once referred to as the “Equations of a God”.

However, Einstein did not fully embrace Kaluza’s approach. Instead, he aligned himself with Max Planck’s perspective, which proposed that spacetime was quantized into discrete units, or “quanta.” This topic will be explored further in a later section.

By the 1930s, Einstein found himself at odds with the emerging quantum mechanics movement, particularly the Copenhagen School. His theory of General Relativity (GR) was not widely accepted by the physics community at the time, and he had to abandon his pursuit of a unified spacetime theory. In the end, he stood alone.

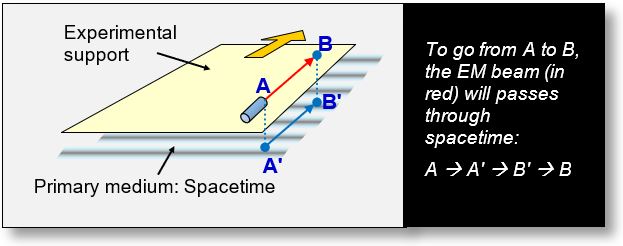

As discussed in Part 1, the gravitational field is supported by the global spacetime structure of the universe. Yet another fundamental field exists: the electromagnetic (EM) field, which is polarized. This chapter will explore its nature.

The Two Known Fields

To explain the laws of the universe, we do not need a multitude of fields, as proposed by string theory. Two fields are sufficient: the gravitational field and the electromagnetic (EM) field.

The gravitational field: Discovered by Einstein in the 1910s, this field has been confirmed by numerous experiments. For instance, GPS technology would not function accurately without corrections based on General Relativity (GR). Part 1 describes the nature and mechanism of this field. Unlike the EM field, gravity affects all particles, whether they are electrically charged or not.

The electromagnetic field (EM): This field governs the electromagnetic force and applies only to charged particles. Physicists have studied it since the 19th century. However, the precise mechanism by which EM waves propagate through spacetime remains unclear.

Both the gravitational and electromagnetic (EM) fields are supported by spacetime — but is this spacetime unique? Certainly not, because the spacetime described by the universe does not account for positive or negative polarities. In fact, polarity is never mentioned in the Einstein Field Equations. See Appendix A5 of the book for the full description of the EFEs.

The issue is that, in order to support EM fields, we require a spacetime framework in which polarities are either explicitly handled or at least acknowledged. This unknown spacetime cannot be the one described by General Relativity (GR) — Einstein’s well-known gravitational spacetime — because GR entirely overlooks the question of polarity.

Different Fields: Examples

1/ Air Mass: To better understand, let’s consider an air mass. We are dealing with two distinct structures that can be likened to two separate spacetimes:

- A 'macro' structure: This refers to the large-scale behavior of the air mass — phenomena such as anticyclones, winds, and storms.

- A 'micro' structure: This operates at the molecular level. Regardless of whether there is wind or a storm, sound waves propagate from molecule to molecule within this structure.

In this example, the two structures coexist and function simultaneously. For instance, one can be in the midst of a storm (macrostructure) while listening to music (microstructure). These two structures are independent of each other.

2/ Water: On Earth, other examples exist. For instance, water can be described as having two distinct structures:

- A macrostructure, formed by large bodies like lakes and rivers.

- A microstructure, at the molecular level. Sound propagates from one H2O molecule to another through this molecular arrangement, which constitutes the microstructure.

In this case, as with air, both structures coexist and operate independently, yet simultaneously.

Von Laue Graphs

Max von Laue (Nobel Prize in Physics, 1914) drew this graph in 1927, which he called the von Laue geodesics. This graph illustrates how light propagates around a mass and complements Einstein’s work.

We can observe that the geodesics bend around the sphere, in a manner similar to gravitational lensing.

The diagram also shows that spacetime is curved by the closed volume of the sphere. However, this curvature does not prevent light from following the geodesic A–A′. In other words, von Laue, without realizing it, depicted a double structure:

- A macrostructure, corresponding to the deformation of gravitational spacetime,

- A microstructure, which guides light along its geodesics. This microstructure corresponds to the electromagnetic (EM) spacetime.

Von Laue thus suggests that the gravitational spacetime of General Relativity contains a subset. This second spacetime, here referred to as EM spacetime, provides the medium through which electromagnetic waves propagate.

Such a double structure is common in everyday life — for instance in air, water, and other media. The existence of a similar dual structure in quantum physics is therefore a plausible hypothesis, and this possibility will be explored in the following pages.

In any case, the propagation of electromagnetic waves must necessarily occur within a structure different from Einstein’s gravitational field, since that field is insensitive to charged particles.

Summary: Fields in Spacetime

A single gravitational spacetime presents a limitation: it does not account for the polarities of charged particles. To address this, a dual structure is required:

Macrostructure: This corresponds to Einstein’s gravitational spacetime, as discussed in Part 1. It governs mass and gravitation but does not incorporate particle polarity (positive or negative). It forms the foundational framework of the universe.

Microstructure: This structure supports wave phenomena and corresponds to electromagnetic (EM) spacetime. It specifically concerns charged particles and electromagnetic waves. It provides the framework that explains, among other things, why the speed of light remains constant at 300,000 km/s.

Conclusion: For a complete and coherent physical model, two distinct structures of spacetime are necessary — the gravitational spacetime and the electromagnetic (EM) spacetime. Even though EM spacetime is invisible, it exists for at least one reason: Einstein's gravitational spacetime does not account for charged particles. The existence of EM spacetime is therefore a necessity.