Interactions in Spacetime

How do interactions work in spacetime?

In Part 2, we examined a well-known interaction among physicists: electron–positron annihilation (e⁺e⁻). Since all particles are composed of spacetime, their interactions follow the same principles as those observed in e⁺e⁻ annihilation.

This chapter is not only relevant to physicists — it also offers valuable insights for anyone seeking a deeper understanding of composite particles.

Basic Principle

The first principle of duality states that any wave can be transformed into a particle — and vice versa. It is essential to remember that both particles and waves originate from spacetime.

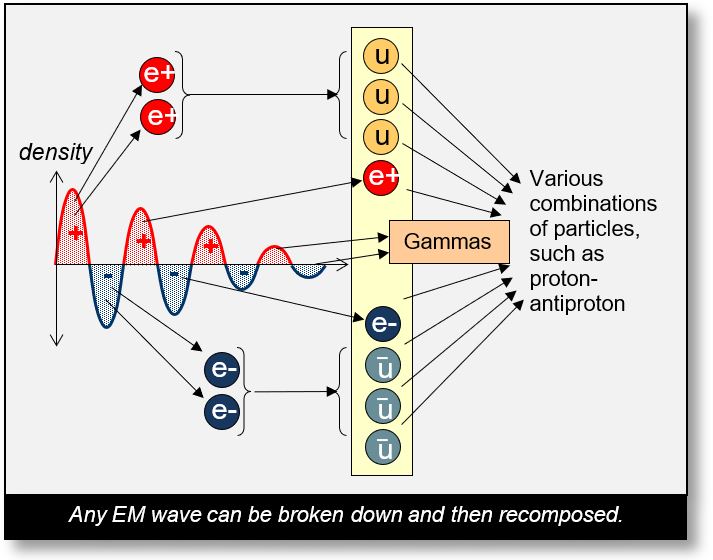

In the example on the next page, we observe the creation of three u-quarks, u-antiquarks, an electron–positron (e⁺e⁻) pair, and a residual gamma photon. All these components emerge from spacetime almost simultaneously, originating from a wave.

One possible outcome in this scenario is the formation of a proton–antiproton pair. However, other composite particles may also be produced. It is crucial to ensure that the number of electrons and positrons remains balanced before and after the interaction1.

Gamma rays from the initial wave serve as a source for multiple possible combinations. In high-energy interactions, the same principle applies: particle jets result from spatiotemporal dynamics triggered by particle collisions.

To generate quarks and antiquarks, two electron–positron pairs must be in close proximity, as illustrated in our example.

1This new perspective — that the universe consists solely of three components: electrons, positrons, and sCells — does not alter Feynman's existing formalism of quantum mechanics.

Spacetime (waves) is transformed into

Spacetime (particles) and vice versa.

---

This duality enables all types

of interactions to occur.

Note: Since all particles are composed of spacetime, it is conceivable that particles predicted by supersymmetry (SUSY) could exist and may be discovered in the future.

Proposed Formulation (for Physicists)

A particle can be defined using the following symbolic representation, designed to complement Feynman diagrams. The particles considered in this framework include electrons, positrons, up quarks (u), and anti-up quarks (/u).

Parentheses indicate that an electron or positron surrounds other fundamental particles. These parentheses must always appear in pairs to reflect confinement or binding. Below are examples previously discussed:

- (u)e⁻ A single u-quark surrounded by an electron — interpreted as a d-quark.

- (u, u, u)e⁻ Three u-quarks surrounded by an electron — representing a proton.

- ((u, u, u)e⁻)e⁻ A proton further surrounded by an electron — representing a neutron.

- (/u, /u, /u)e⁺ Three anti-up quarks surrounded by a positron — representing an antiproton.

- And so on...

In this model, the electron and positron serve as confining agents, analogous to the strong nuclear force. Since this force is essential for the stability of any composite particle, we propose the following rule:

All composite particles must include

at least one electron or positron to

generate the strong nuclear force.

... or, translated into nuclei, which leads to:

All nuclei — except 1H, 3Li, diproton ...— must contain at least one neutron to

generate the strong nuclear force.

Composite particles require confinement by electrons or positrons, which act as carriers of the strong interaction in this representation.

Notably, exceptions such as 1H, 3Li, 2He, the diproton, and Δ++ support this rule. Each exception yields a rational explanation within the framework, reinforcing the validity of the Wave Model as a more accurate and unified theory.

Furthermore, these anomalies suggest that traditional spin-based models are outdated and warrant revision.

Note: While many other particles — such as muons, taus, and others — are not explicitly discussed in this chapter, the core principle remains unaffected by their specific nature. The formulation presented here applies independently of these additional particle types.

Summary of Particles

Interactions in Spacetime

This page has demonstrated that particles are fundamentally manifestations of spacetime — appearing as localized entities when at rest and as waves when in motion. Within atomic nuclei, these particles behave as dynamic charge clouds.

Consequently, a single electromagnetic (EM) wave, provided it carries sufficient energy, can give rise to any particle or combination of particles. This principle, introduced in Part 2, is supported by experimental observations.

As an illustrative case, we examined the decomposition of an EM wave into a proton–antiproton pair. All other particle combinations follow the same underlying mechanism. It is essential to recall that three quarks can be formed from two electrons or positrons — and vice versa.

This page also introduces a compact representation of interactions. This new formalism offers a simplified yet insightful perspective on the strong nuclear force — one not explicitly depicted in traditional Feynman diagrams. Nonetheless, both the Feynman approach and the Spacetime Model can coexist and complement each other in describing particle interactions.