Nucleons and Gluons

What’s Really Inside a Proton?

We have seen that protons and neutrons are each composed of three quarks: (u u d) for the proton and (u d d) for the neutron. If we approach this configuration with logic and common sense, several puzzling questions arise:

- What is the spatial arrangement of these quarks inside the nucleon?

- What is exactly the nature of the force that confines them?

- Why is the mass of the proton or neutron significantly greater than the combined mass of the three quarks?

- What is the origin of gluons?

- How can protons and neutrons be perfectly spherical if their three quarks are arranged in triangles or other geometric shapes?

- And so on...

To date, these questions have received answers that often seem irrational or unsatisfying. This chapter aims to explore these enigmas — not through mathematics, but through logic and common sense.

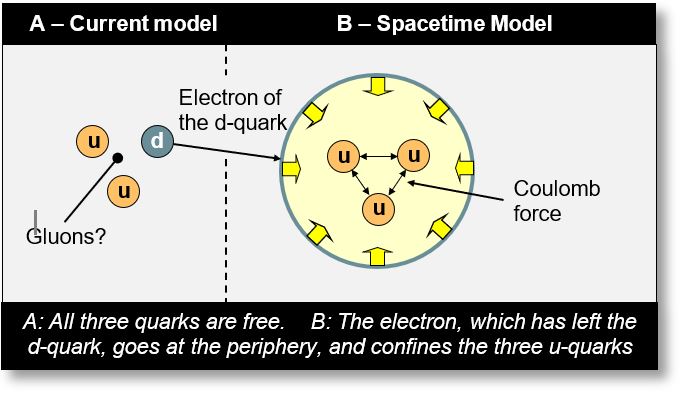

Protons

The Wave Model suggests that the commonly accepted quark structure of the proton — (u u d), as shown in figure A below — is incorrect. Instead, the configuration (u u u) + electron, illustrated in figure B, is considered more accurate. However, the actual arrangement of the quarks differs from what is depicted in that figure.

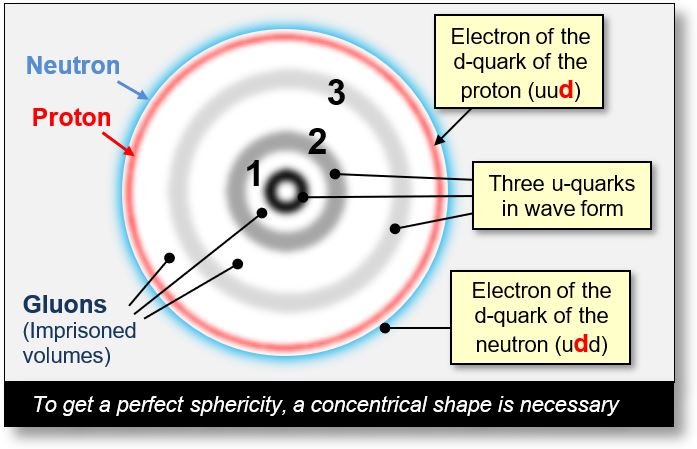

According to the Spacetime Model, the three quarks (u u d) are not bound by a hypothetical nuclear force known as "gluons," whose origin remains unexplained. Nature, it argues, is more straightforward. When a proton is formed, an electron surrounds the three u-quarks in the form of a charge cloud, effectively confining them (see figure B).

This electron behaves like a rubber band: the farther a quark moves from the center, the stronger the restoring force becomes. This description aligns perfectly with the concept of asymptotic freedom, discovered by H. David Politzer, David J. Gross, and Frank Wilczek — recipients of the 2004 Nobel Prize in Physics.

Neutrons

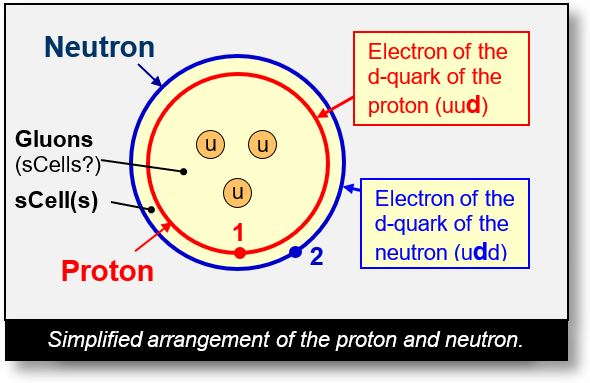

The figure on the next page illustrates a proton and a neutron. The proton consists of two up quarks (u) and one down quark (d). Let us focus on the down quark. The electron associated with the d-quark separates from it and relocates to the periphery (red circle), forming a charge cloud that encompasses the three up quarks.

The neutron, by contrast, can be viewed as a proton with an additional electron on its periphery (blue circle). This electron originates from the second down quark of the neutron and has two key effects:

- It neutralizes the positive charge of the proton, rendering the neutron electrically neutral.

- It expands the enclosed volume of the proton, thereby increasing its mass — transforming it into a neutron.

The following paragraph offers supporting evidence for the validity of this model.

In one of his diagrams (further down the page), Richard Feynman — recipient of the 1965 Nobel Prize — provides a particularly compelling indication. This figure, widely acknowledged by physicists, depicts the neutron as being composed of a proton and an electron, interacting via a W⁻ boson.

Confirmation by Experimentation

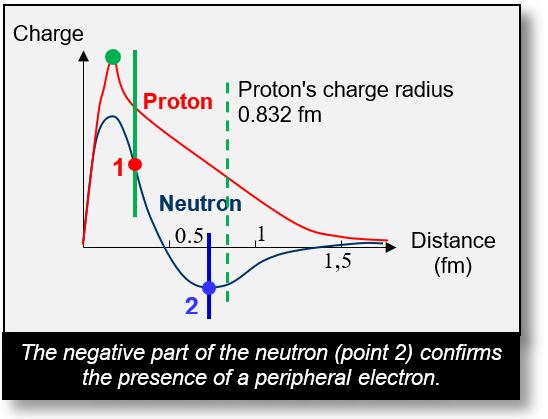

The figure on the next page represents a proton and a neutron. A negative charge in the neutron (marked by blue dot '2') appears at approximately 0.5 femtometers (fm), or 10-15 meters. The origin of this phenomenon remains unexplained by physicists, especially considering that the neutron is traditionally understood to contain no internal negative charge.

However, the figure below — along with the one above — offers a rational explanation. Red and blue reference dots have been added to both figures for clarity.

- Charge Radius: To establish a scale, a vertical dotted line has been drawn at 0.832 fm, representing the proton’s charge radius. The neutron, being electrically neutral, does not possess a defined charge radius.

- Red Dot '1': This dot marks the approximate location of the neutron’s first electron — specifically, the electron originating from the d-quark of the proton. Around 0.2 fm (green dot), the positive charge from the remaining three u-quarks reaches its maximum. Beyond 0.2 fm, this charge gradually diminishes due to the influence of the peripheral electron (red dot '1').

- Blue Dot '2': The blue dot indicates the position of the neutron’s second electron, located on its periphery.

In summary, blue dot '2' marks the location of the peripheral electron that surrounds all internal components of the neutron, including the proton. This electron contributes to the generation of the strong nuclear force. However, it is important to note that this force is already present due to the first electron (red dot '1'), which confines the u-quarks within the proton. The second electron (blue dot '2') therefore serves to reinforce the proton’s nuclear binding.

The neutron's negative charge at point 2 is due to the second electron, that one which was previously present in one of the neutron's d-quarks.

This graph provides evidence that:

- The neutron consists of an electron encircling a proton, which calls for a reassessment of current spin theories.

- The Wave Model, as supported by this data, offers a coherent framework for understanding the structure of elementary particles.

This graph proves that the neutron is composed of a proton and an electron.

Asymptotic Freedom

Unlike other forces whose intensity diminishes with distance, the strong nuclear force becomes stronger as separation increases — a phenomenon known as asymptotic freedom. Physicists often illustrate this behavior using the analogy of a rubber band: the farther it is stretched from its center, the greater the restoring force.

This is precisely the role played by the electron in the Spacetime Model. Like a rubber band, the peripheral electron encircles the three up quarks (u-quarks), confining them and preventing them from drifting apart. In this view, the strong nuclear force does not exist as a distinct entity; rather, the electron exerts a simple elastic force — akin to Hooke’s law — that maintains the cohesion of the quarks.

The Wave Model provides a clear explanation for the origin of the strong nuclear force and the theory of asymptotic freedom.

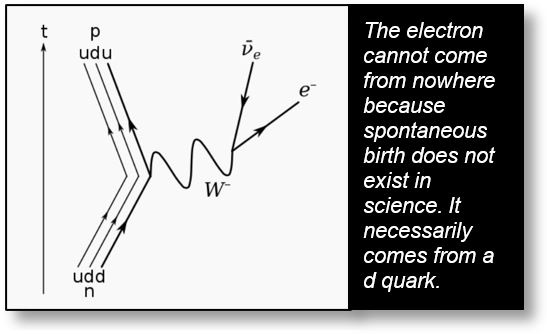

Feynman diagram

The "Feynman diagram" is commonly used to represent particle interactions. As an example, we will briefly examine the transformation of a neutron into a proton.

The following Feynman diagram illustrating this interaction is widely accepted within the physics community. It depicts the production of an electron. However, the origin of this electron remains unexplained. We are thus confronted with the following alternatives:

- The electron appeared from nowhere — an assumption that clearly contradicts the foundational principles of science.

- The electron originates from one of the neutron’s down quarks (d), which is transformed into an up quark (u). This is indicated in the Feynman diagram: (u u d) → (u d u). The diagram also includes an intermediate particle — the W⁻ boson. More precisely, this particle can be interpreted as a "matter wave" (see Part 4). Its identity is not essential, since all phenomena are manifestations of spacetime. Whether we label this intermediate particle W⁻ boson, X, Y, or Z is ultimately irrelevant (see Parts 2 and 4).

Furthermore, evidence supporting the idea that a neutron consists of a proton and an electron is provided by other experiments, including the graph shown above.

This Feynman diagram clearly and unambiguously shows that the emitted electron originates from one of the neutron’s d-quarks, which transforms into an u-quark.

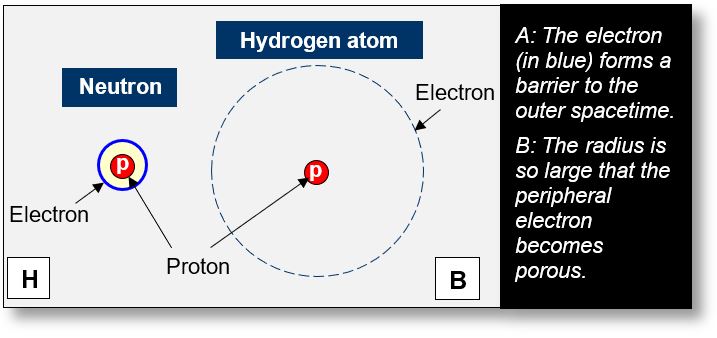

Neutron vs. Hydrogen Atom

As illustrated in the figure below, both the neutron and the hydrogen atom are described using the Wave Model. In both cases, the electron — represented as a cloud of charge — surrounds the proton.

However, a key difference exists between these two systems. In the neutron (A), the peripheral electron generates a hermetic volume, which is responsible for the emergence of mass. In contrast, in the hydrogen atom (B), the electron forms an open volume, which is non-massive due to the nature of Schrödinger’s orbitals.

Let us consider the following analogy:

Imagine a small island in Alaska, measuring 1 km in diameter and surrounded by floating ice. This ice acts as a protective barrier against storms, forming a 'closed volume'. Now imagine redistributing the same amount of ice along the circumference of a circle with a radius of 100 km. Instead of a protective barrier, we now have scattered ice fragments that offer no real defense against storms. The previously 'closed volume' has become an 'open volume'.

This analogy reflects the distinction between neutrons and hydrogen atoms, which are based on the same underlying principle:

- Neutron: The peripheral electron exhibits a high density of spacetime, forming a barrier that prevents external spacetime from penetrating the particle’s interior. This results in a hermetic volume. Since the neutron is composed of a proton and an electron, it induces a curvature in spacetime — producing a mass effect (see Part 1).

- Hydrogen Atom: In this case, the diameter of the peripheral electron’s orbital is so large relative to the nucleus that its spacetime density is highly diluted and porous. This diluted state allows spacetime to permeate the atom. Consequently, the curvature of spacetime — and thus the mass — is concentrated solely around the nucleus.

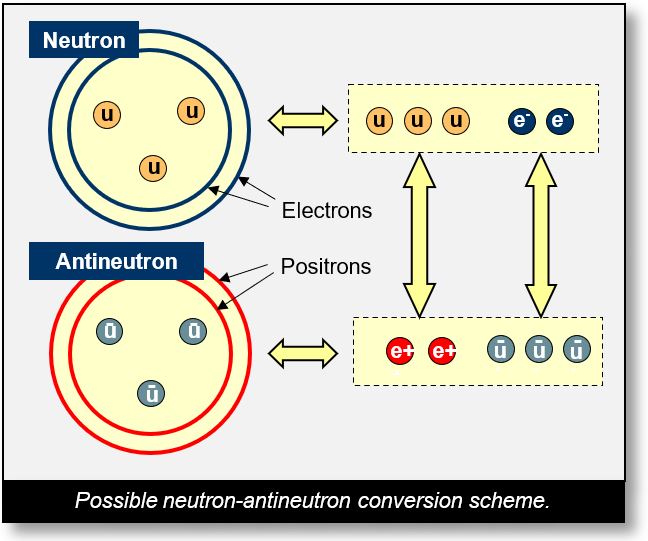

Antineutrons

The transformation of a neutron into an antineutron is a theoretical possibility, provided sufficient energy is available. The proposed sequence unfolds as follows:

- The neutron decays into three up quarks and two electrons.

- These three up quarks are recombined into two positrons.

- The two electrons bind with one or more sCell(s) to generate three anti-up quarks.

- The two positrons then surround the three anti-up quarks, forming an antineutron.

Equality of Proton and Electron Charge

The electric charge of the proton is exactly equal to that of the electron. High-precision measurements confirm this with an uncertainty margin as low as 10−21 C. This raises a fundamental question: How can we account for such perfect charge symmetry between two seemingly distinct particles?

Our Wave Model offers a remarkably simple explanation:

- The proton is traditionally described as being composed of three quarks: (u u d).

- However, in our model, the d-quark is actually a u-quark enveloped by an electron.

- As previously discussed, three quarks (u u u) are formed from two positrons.

- This configuration yields a total charge of +2 with extremely high precision.

- Subtracting the electron associated with the d-quark gives "+1", which matches the proton’s observed charge.

In essence, there is only one plausible mechanism to achieve this exact charge balance: the quarks within the proton must originate from combinations of electrons and positrons.

The figure below illustrates a complete construction of both the proton and the neutron according to this model.

The charge and mass of the positron may differ slightly from those of the electron, though only by infinitesimal amounts. For further discussion, refer to the paragraph on neutrinos.

Sphericity

As discussed in Part 1, mass arises from a closed volume. Regarding particle geometry, two possibilities emerge:

- Perfectly spherical particles yield consistent measurements regardless of the angle of observation. This applies to electrons, muons, taus, protons, neutrons, and possibly the top quark.

- Aspherical particles, on the other hand, may produce inconsistent measurements due to the uneven distribution of mass and/or charge in three-dimensional space. For example, up quarks (u-quarks) exhibit significant measurement dispersion, ranging from 1.9 MeV/c2 to 2.2 MeV/c2. This suggests that the u-quark is not spherical. Consequently, the down quark (d-quark) — which is modeled as a u-quark surrounded by an electron — is also not spherical. This interpretation is supported by experimental data, reinforcing the idea that the d-quark is essentially a composite of a u-quark and an electron.

The greater the sphericity of a particle, the lower the dispersion in its measurements — potentially reaching zero for perfectly spherical particles.

From these observations on sphericity, we can infer the spatial arrangement of elementary particles within composite particles.

In particular, for protons and neutrons to exhibit perfect sphericity, their constituent quarks must exist in wave form. This configuration is illustrated in the figure below1.

1The d-quarks are not shown in the figure below because they do not exist as distinct entities within the particles. During interactions, a u-quark can instantly transform into a d-quark by capturing an electron. From an external perspective, this may give the impression that the nucleus contains d-quarks. However, it actually contains only u-quarks — composed of positrons and electrons in various configurations.

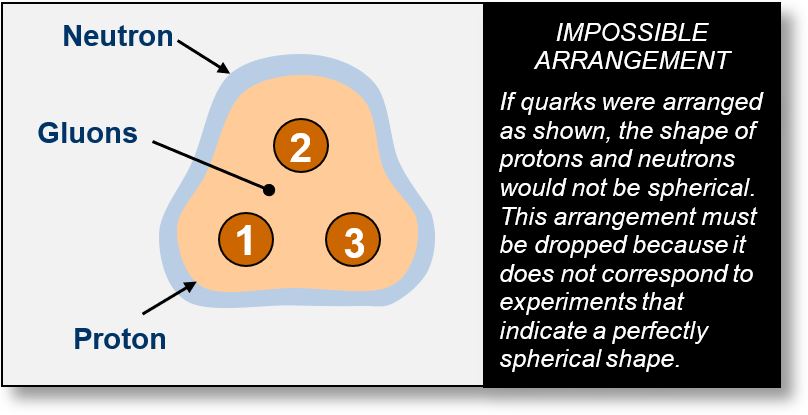

Possible Scheme for Gluons

Experiments show that protons and neutrons are perfectly spherical. However, achieving a spherical geometry with only three discrete particles is theoretically impossible. The figure below illustrates a possible spatial arrangement of the three quarks treated as individual particles.

To achieve perfect sphericity, a concentric configuration is required, as shown in the figure below. No other arrangement can produce such symmetry.

Perfect Sphericity of the Proton Requires:

- Quarks must exist in wave form rather than as discrete point particles.

- Their wave distributions must be concentric, ensuring uniform symmetry around the center.

Overview of Quark and Gluon

d-quarks: Down quarks are not present in certain composite particles such as the proton or neutron. In these nucleons, the d-quarks have lost their associated electrons and consequently transformed into u-quarks. The released electron migrates to the periphery of the nucleus, forming a charge cloud that confines the three remaining u-quarks. This configuration offers a logical explanation for both the strong nuclear force and the phenomenon of asymptotic freedom.

Concentricity: The u-quarks within protons and neutrons — and likely within other composite particles — exist in wave form. This wave-like nature enables a concentric spatial arrangement, which is the only configuration capable of ensuring perfect sphericity.

Gluons: Because u-quarks carry a positive charge, they are subject to repulsive Coulomb forces. This repulsion generates spatial separation between the three u-quarks, creating enclosed volumes within the hermetic boundary of the proton or neutron (see Part 1). This structural feature accounts for the mass discrepancy between nucleons and their constituent quarks.

Sphericity: Investigating the sphericity of particles can yield valuable insights into the internal arrangement of quarks within nucleons and other composite systems.