Electromagnetic Fields

Rethinking Electromagnetism

Significant discoveries have been made in recent decades in the field of electromagnetism, particularly regarding coherent light sources such as lasers. Yet, the fundamental nature of a simple light ray — or electromagnetic (EM) wave — remains poorly understood.

One of the most persistent challenges in physics is the wave–particle duality. This paradox was addressed in Part 2. Building on that insight, we now propose a new interpretation of the photon and the underlying mechanisms of electromagnetism.

sCells

The closed volume (or "volume having mass") of the electron has been measured with remarkable precision: 510.998918 keV/c2. Its boundaries are therefore clearly defined. Such accuracy invites us to question the true origin of the electron.

Part 3 suggests that the Standard Model may have been constructed from fundamental units called sCells, which merged to form electrons and positrons. It appears that the entire universe could be composed of these sCells.

It is plausible that sCells represent open volumes with an energy equivalent of 510.998918 keV/c2. Indeed, Part 5 indicates that the boundaries of sCells are exceptionally well-defined. Yet, the propagation of the electron’s charge — interpreted here as a manifestation of spacetime density — remains an unresolved mystery. How can the electromagnetic field extend beyond the sharply defined boundaries of the electron? exceptionally well-defined.

Density of sCells: Electrons and Positrons

sCells possess a neutral spacetime density, a condition required by the overall neutrality of the universe, which is neither positively nor negatively charged.

However, sCells may exhibit densities slightly above or below the average spacetime level, provided that the universe as a whole remains neutral (see Part 5).

As previously stated, the three fundamental constituents of the universe are:

- Neutral sCells (referred to simply as "sCells")

- Positive sCells (positrons)

- Negative sCells (electrons)

The following example helps clarify the process.

Consider a neutral sCell with a charge of 100. If 5% of its charge is transferred to a neighboring sCell, the recipient sCell will now carry a charge of 105, while the original sCell will be reduced to 95. The total charge remains balanced (105 + 95 = 200), preserving neutrality. However, instead of two neutral sCells with equal charge, we now have a positively charged sCell (105), identified as a positron, and a negatively charged sCell (95), identified as an electron.

Inside the sCells

The spacetime density within an sCell is both neutral and uniform.

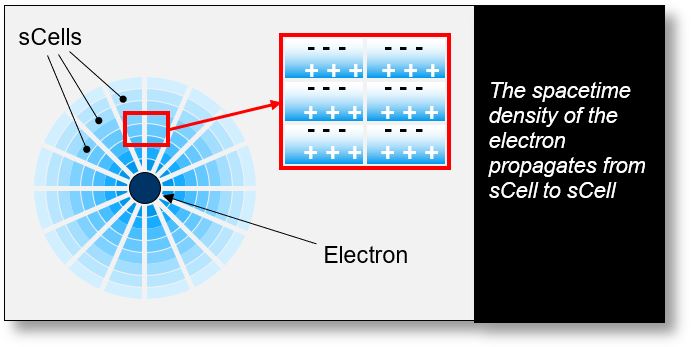

Let us imagine a neutral sCell positioned near a charged sCell — such as an electron or a positron. The figure below illustrates this scenario using the example of an electron. What occurs in this configuration?

The central electron attracts the positive part of spacetime from the adjacent sCell. As a result, one side of the neighboring sCell experiences spacetime compression, while the opposite side undergoes a form of depression, as depicted in the red inset. In essence, the positive region of an sCell is drawn toward the negative region of the adjacent sCell — and vice versa.

This attraction–repulsion dynamic continues to affect surrounding sCells, creating a chain reaction. Ultimately, the electric field propagates from sCell to sCell, with each acting as a miniature electric dipole.

This phenomenon can also be observed in everyday life. For instance, in the image below showing a small permanent magnet and five steel nuts, magnetization is transferred from nut to nut, atom to atom, and thus from sCell to sCell within each nut.

The 1/d2 Rule

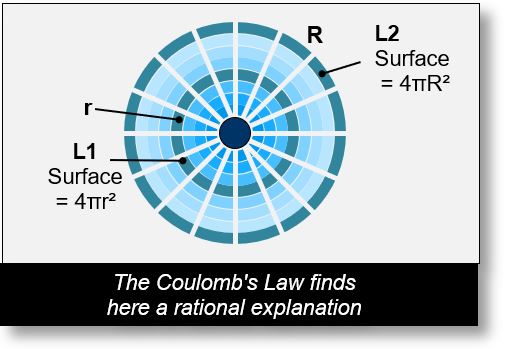

Let us consider the following example. On layer L1 in the figure below, we have 1000 sCells. On layer L2, located at a greater distance, the number of sCells, denoted by N, will be:

N = 1000 x 4πR2/4πr2 = 1000 R2/r2

This simple calculation shows that the number of sCells is proportional to the surface area of the layer — that is, to the square of the distance from the source. The farther the layer, the more sCells it contains, which in turn reduces the charge per sCell. This confirms the inverse-square law, or 1/d2 rule.

For example, if we have 1000 sCells on a given layer, then on a layer located twice as far, we will find 4000 sCells. Since the surface area increases by a factor of 4 when the distance doubles, the charge per sCell is divided by 4. Thus, the total charge remains constant: 4000 / 4 = 1000.

The 1/d² Distribution of sCell Charge:

A Coulombian Confirmation

Electrical Polarization of sCells

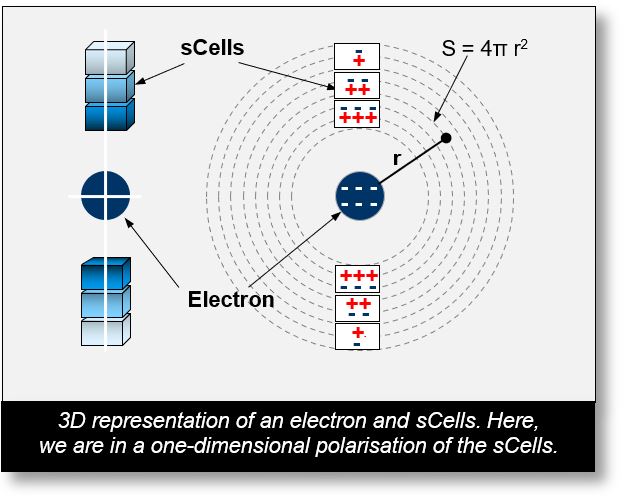

Let us adopt spherical symmetry coordinates, r, φ, and θ, instead of the Cartesian coordinates x, y, and z.

The electrical polarization described in the previous paragraphs depends solely on the radial distance r. At any given radius from the center, the sCells are polarized identically, regardless of the angular coordinates φ and θ. This behavior is expected due to the system’s spherical symmetry.

The figure on the left presents a 3D view of a static electron surrounded by six sCells. As previously noted, the spacetime density within each sCell decreases proportionally to 1/r² with increasing distance r.

The figure on the right shows a cross-sectional view of these cells. When the electron is at rest, only an electric field is generated. This results in a one-dimensional polarization along r.

The electric field represents a radial

(1D) polarization of the sCells,

depending solely on the radius r.

Magnetic Polarization of sCells

We know that:

- Electromagnetism manifests only when a charged particle is in motion.

- Maxwell demonstrated that the electric and magnetic fields are two distinct manifestations of the same underlying phenomenon, occurring in different contexts—namely, when the particle is at rest versus when it is moving.

Since the radial coordinate r is already associated with the electric field, we can conclude that the magnetic field must involve the remaining coordinates, i.e. the angular components φ and θ.

This interpretation aligns with experimental observations accumulated over the past two centuries. To describe magnetism, we require vector components that are mutually perpendicular, whereas the electric field can be defined using a single radial vector. This principle is commonly illustrated in schools using the "three-finger rule" (or right-hand rule), which visually represents the orthogonal relationship between electric field, magnetic field, and particle motion.

Beyond the radial electrical polarization denoted by r, magnetic polarization

occurs along the angular directions

φ and θ in space.

Principle of Electromagnetism

Why does this type of polarization only appear in specific situations where the electron is in motion? Here's the explanation.

The small square shown in the figure on the next page, which includes the point x, represents a region located at a certain distance from the electron. This region could, for example, correspond to a measuring device.

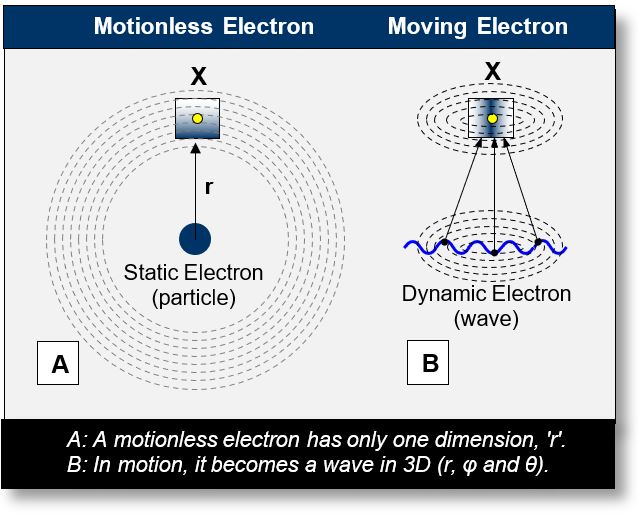

The figure above illustrates two scenarios:

- (A) Motionless Electron: A stationary electron corresponds to a negatively charged sCell — essentially a static negative zone of spacetime. As previously described, the electric field propagates from one sCell to another. In this configuration, each sCell is polarized along a single axis: the radial coordinate r. This one-dimensional (1D) polarization is consistent with experimental observations of electric fields. Consequently, the point x is influenced only along this radial direction, and its interaction is confined to a single dimension.

- (B) Moving Electron: When the electron transitions from a particle to a wave (see wave–particle duality in Part 2), the point x becomes immersed in fields originating from multiple sources, as illustrated by the blue wave in Figure B. The corpuscle X transforms into a wave due to its motion. This wave introduces an additional two-dimensional spatial structure, characterized by the angular coordinates φ and θ. The concentric ellipses in Figure B offer a perspective view of this newly generated 2D aspect of the wave.

To summarize, when the electron is in motion, external points such as x are influenced in three dimensions: r, φ, and θ.

Magnetic Monopoles

The existence of magnetic monopoles has never been confirmed experimentally. However, this does not mean they are impossible — we may not yet understand how they could exist, but we must never say “never.” Several laboratories are currently investigating this intriguing possibility.

Summary

The Basics of Electromagnetism

The electric field — also known as the Coulomb field — can be interpreted as a simple polarization of sCells along a single spatial dimension: the radial coordinate r. In contrast, the magnetic field represents a kind of “lateral” Coulomb field, emerging specifically in the angular dimensions φ and θ. These two dimensions complement the radial component r, transforming the magnetic field into a three-dimensional structure defined by r, φ, and θ.

To simplify:

- Motionless particle (corpuscle): When the particle is at rest, it behaves as a corpuscle. Its electric field is one-dimensional, depending solely on the radial distance r.

- Moving particle (wave): When the particle is in motion, it transitions from corpuscle to wave, as described by wave–particle duality. The electric field remains, but the motion introduces two additional spatial dimensions, φ and θ. As a result, magnetism emerges in three dimensions: r, φ, and θ.