Spin

The Enigma of Spin:

Real, Useful… But What Is It?

Before discussing the photon, we chose to begin with spin, as it is a fundamental concept in quantum mechanics.

Spin is one of the intrinsic properties of elementary particles, composite particles, and atomic nuclei. The challenge with spin lies in the fact that no one truly knows what it is. We know it exists and behaves consistently in 99% of cases, yet its nature remains elusive.

Spin is incorporated into several major theoretical frameworks: Dirac’s Relativistic Quantum Mechanics, Quantum Field Theory (QFT), the Standard Model of Particle Physics, and Supersymmetry (SUSY)... but none of these offer a fully rational or intuitive explanation.

This page proposes a plausible interpretation of spin, though non-specialists may overlook its significance on a first reading.

History of Spin

In 1925, Kronig, Uhlenbeck, and Goudsmit proposed that particles rotate around their own axis—hence the term spin. A mathematical framework was developed by Wolfgang Pauli in 1927 (Nobel Prize, 1945). In 1928, Paul Dirac (Nobel Prize, 1933) formulated relativistic quantum mechanics, which naturally incorporated the electron’s spin. Spin also appears in the formalism of Schrödinger’s equation, although not explicitly.

In quantum mechanics, two types of angular momentum are distinguished: orbital angular momentum, which derives from classical mechanics, and spin, which has no classical analogue.

Spin has the same physical dimensions as angular momentum. However, in practice, physicists do not express spin using SI units. Instead, it is quantified in multiples of the reduced Planck constant, ħ (see definition in the next paragraph).

Over time, the factor ħ was often omitted in notation. As a result, spin values came to be expressed as dimensionless quantities such as 0, 1/2, or 1 — though the presence of ħ remains implicitly understood.

Planck Constant: h or ħ

Planck’s constant h is a fundamental quantity widely used in quantum mechanics. Its value is approximately 6.626 × 10-34 J·s (joules-seconds), and its dimensional formula is [ML2/T].

In quantum mechanics, a more convenient variant of h is often used: the reduced Planck constant, denoted ħ (pronounced “h-bar”). It is defined by the relation: ħ = h/2π. Both h and ħ share the same dimensional quantity [ML2/T].

In many quantum formulations, ħ is preferred over h. When this substitution occurs, the frequency ν (Greek "nu") is replaced by the angular frequency ω, defined as: ω = 2πν (or equivalently, ω = 2πf, where f is the frequency in hertz, just like ν).

Angular frequency ω is commonly used not only in quantum mechanics but also in electronics and electrical engineering.

As discussed earlier, Planck’s constant plays a central role in the quantification of electromagnetic radiation energy, expressed by the equation: E = hν where ν is the frequency of the radiation. Planck’s constant (h or ħ) also appears in other domains, such as the calculation of atomic orbitals in quantum mechanics, notably in Schrödinger’s equation.

Possible Explanation of Spin

Since spin is not proportional to either charge or mass, it may be linked to another intrinsic property. One candidate, based on current understanding, is the waveform of the particle in motion.

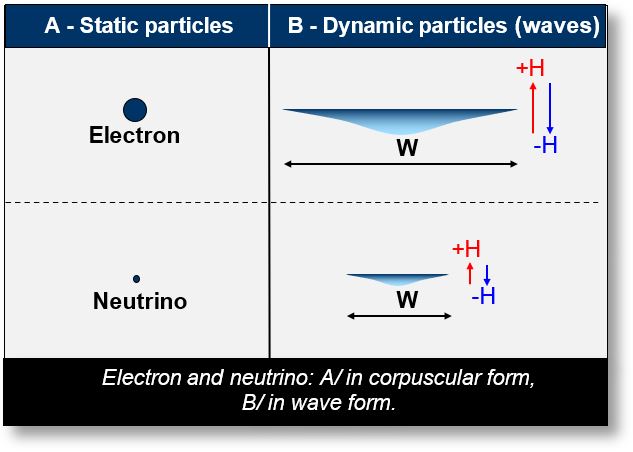

In the figure below, two particles — an electron and a neutrino — are shown moving toward the observer.

- Left side (A): The two particles are at rest. If spin is indeed a parameter associated with motion, it should not manifest when the particle is stationary. Accordingly, the particles are depicted in their corpuscular (particle-like) form.

- Right side (B): The same particles are now in motion and represented as matter waves.

Interestingly, both the electron and the neutrino — despite their differences — share the same spin value: 1/2.

Examining their waveforms (side B of the figure), we notice a common geometric feature: the aspect ratio, expressed as H/W (Height over Width). This ratio is noteworthy because, like spin, it is a dimensionless quantity (aside from the implicit presence of ħ in spin quantization).

One immediate idea is that spin could correspond to a simple H/W ratio (height over width), implicitly scaled by Planck’s constant ħ.

This interpretation suggests that a particle at rest cannot possess spin, since the H/W ratio would be undefined in the absence of motion. According to the Spacetime Model,

Spin would only emerge

when the particle is in motion.

If this perspective holds, spin would not be an intrinsic property of the particle itself, but rather a dynamic feature associated with its movement

Another intriguing possibility is that spin represents a polarization direction of sCells. Under this assumption, the spin projection along any axis would yield two possible values: +H/W and –H/W.

Spin Values

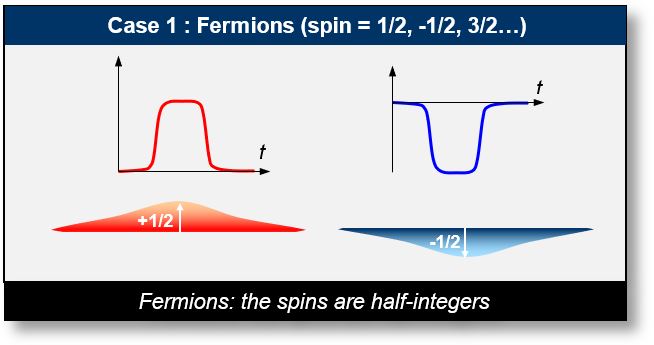

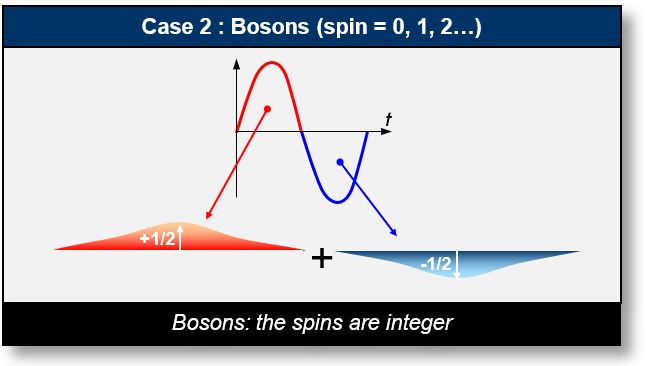

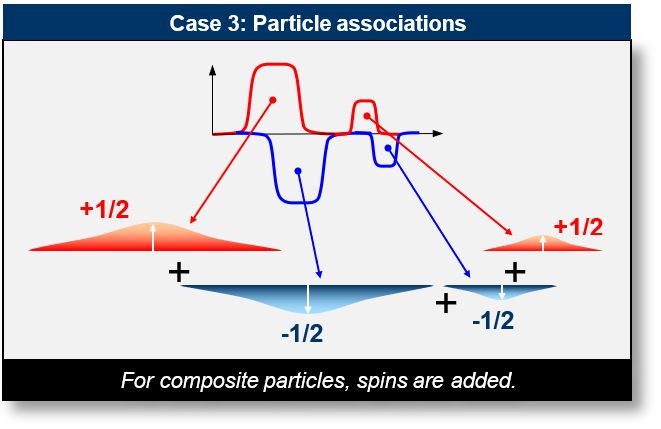

The three figures below — Figures 1, 2, and 3 — illustrate the different cases to consider:

- Case 1: Basic Particles (Fermions): These particles, often described as "matter waves," include electrons, neutrinos, and quarks. Their spin values are always half-integer multiples of ħ (the reduced Planck constant). The projection of spin along a given axis depends on the polarization of the sCells, which can be either positive or negative.

- Case 2: Electromagnetic Bipolar Waves (Bosons): In this case, the waveform consists of half-periods that cancel each other out, depending on the wave structure. Particles with integer spin values — such as photons or gluons — are classified as bosons.

- Case 3: Composite Systems: This scenario involves a set of half-periods originating from multiple particles. For example, a nucleus behaves as a complex superposition of waves, resulting in a collective spin pattern.

A Word of Caution It’s important to remember that this information is purely hypothetical. Experimental validation is essential before any firm conclusions can be drawn.

As with any emerging theory, exceptions may arise. If so, the hypothesis should not be dismissed outright, but rather examined and refined accordingly.

In any case, this approach offers a starting point — arguably no worse than the current situation, where the true nature of spin remains fundamentally unknown.

The Spin Crisis

An enduring enigma in quantum mechanics is the so-called spin crisis.

Prior to the 1980s, it was widely believed that quarks accounted for the entire spin of the nucleon. However, experimental results failed to confirm this assumption. In the late 1980s, the European Muon Collaboration (EMC) conducted experiments that revealed quarks contribute only a fraction of the nucleon's total spin.

This unexpected finding stunned particle physicists and gave rise to the challenge now known as the spin crisis: the quest to identify the source of the missing spin. The mystery persists, and progress remains stalled until we gain a clearer understanding of what spin truly is. It is evident that further research must focus not merely on resolving the crisis, but on fundamentally grasping the nature of spin itself.

Experimental research on this topic has been carried out in various laboratories, including the Spin Muon Collaboration (SMC), CERN, SLAC, DESY, and Jefferson Lab (JLab). Comprehensive analysis of the data from these experiments confirmed the original findings of the European Muon Collaboration (EMC), demonstrating that quark spin accounts for only about 30% of the total nucleon spin.

Suggested Explanation of Spin

In Part 2, the wave–particle duality suggests that when a particle moves at low velocity, its form lies between a corpuscle and a wave. These intermediate states may offer insight into unresolved phenomena in quantum mechanics, including the spin crisis.

Indeed, such transitional configurations could correspond to non-standard spin values—for example, a spin of 1/4 instead of the conventional 1/2. This hypothesis is further developed, where the relationship between waveform geometry and spin quantization is explored.

Spin Problems

The proton was discovered in 1919 by Ernest Rutherford (Nobel Prize, 1908), and the neutron followed in 1932, identified by James Chadwick (Nobel Prize, 1935). The concept of spin emerged between 1925 and 1935, during a formative period in quantum theory.

And yet, after a century of advances in particle physics, the true nature of spin remains a profound mystery. This prompts a fundamental question: Is it still reasonable to apply theoretical rules from 1925 to a phenomenon we scarcely comprehend today?

Quarks, discovered in 1964 — nearly 30 years after spin was first theorized — have reshaped our understanding of matter. Wouldn’t it be more reasonable to revisit and revise the foundational assumptions about spin in light of modern discoveries?

Extrapolating the spin rules formulated

in 1925 to quarks — particles only discovered in 1964 — is a hazardous endeavor.

Bose–Einstein Condensate

This section is primarily intended for physicists and is presented as a theoretical suggestion.

The perspective offered by both the Spacetime Model and the Wave Model appears to find support in an experimental phenomenon: the Bose–Einstein Condensate (BEC).

Helium atoms, for instance, become superfluid at temperatures approaching absolute zero (−273.15° K). Physicists typically interpret this behavior as a manifestation of quantum state superposition, although the precise mechanisms remain unclear. The Spacetime Model proposes a simpler and potentially more intuitive explanation.

If we accept the premise that spin arises only when a particle is in motion (see the wave-particle duality explanation in Part 2), then at −273° K — where particles are effectively motionless — spin should theoretically vanish. In such conditions, the wave-like nature of particles collapses into a corpuscular form, rendering the Pauli exclusion principle inapplicable.

As previously discussed, atomic orbitals are organized into shells. At absolute zero, these orbitals may either vanish or become entirely disordered, consistent with the transition from electron-waves to electron-particles.

Take neon as an example: it has two electrons in the first shell and eight in the second. If the orbital structure collapses, all ten electrons may exist in particle form, potentially occupying a single shell. In this state, the Wave Model ceases to apply, and Pauli’s principle no longer constrains electron configuration. The result is a single orbital accommodating all electrons.

These intermediate states near absolute zero challenge conventional atomic models and invite a reconsideration of quantum behavior under extreme conditions.

Research Approaches to Spin

The spin theory presented in this chapter leads to four key consequences, which can be inferred from the preceding figures:

Neutrinos must possess a non-zero electric charge, given that they exhibit a spin of 1/2. This challenges the conventional assumption of neutrino neutrality and invites further experimental scrutiny.

Spin vanishes when a particle is at rest. If spin is intrinsically linked to motion — as proposed by the Spacetime Model — then a motionless particle cannot exhibit spin, redefining its role as a dynamic rather than intrinsic property.

The Spacetime Model may offer deeper insight into atomic behavior near absolute zero. This could open pathways to novel applications such as ambient-temperature superconductivity, universal nuclear fusion across all nuclei types, and other quantum phenomena.

At −273° K, a compelling experiment would be to induce a photoelectric (PE) effect while all electrons occupy the first shell. In this state, the collapse of orbital structure and wave behavior may allow for exceptionally high efficiency in electron emission.

Spin Explained:

Beyond the Classical Intuition

Spin is a fundamental property of elementary and composite particles, as well as atomic nuclei. Although it resembles angular momentum, spin is not a classical kinetic moment. The absence of a classical analogue in terrestrial physics makes it difficult to define spin precisely.

One possible explanation is proposed here: spin may correspond to the aspect ratio (Height/Width) of a matter wave or electromagnetic bipolar wave. This idea remains speculative and requires experimental validation.

Key points:

- The rules for spin addition apply reliably to atoms.

- A particle at rest does not possess spin.

- At absolute zero, electron orbitals vanish, and the Pauli exclusion principle ceases to apply.

- A particle moving at very low speeds may exhibit a spin value different from 0 or the usual half-integer multiples (to be verified).

- The neutrino may carry a non-zero electric charge, inferred from its spin of 1/2. This spin value could serve as indirect evidence of its charged nature.

Potential applications include:

- Superconductivity at ambient temperatures

- Universal nuclear fusion across all types of nuclei

- Highly efficient photoelectric effects