Wave Model

What the Wave Model Really Means

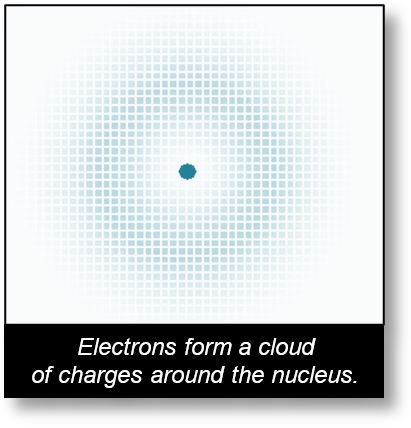

Contrary to conventional scientific models, within atoms, the electron does not orbit the nucleus as a discrete corpuscle. Instead, its charge is distributed across multiple sCells, forming a diffuse cloud of electric potential around the nucleus. Equipotential Coulomb forces maintain stability and prevent annihilation.

This revised framework sheds light on several longstanding enigmas, including the nature of the strong nuclear force, the structure of quarks, and the composition of protons and neutrons.

Electrons in Atoms

The figure below illustrates an atom in which the electron’s electric charge is distributed in a wave-like manner. Through the principle of duality, we have shown how the electron — traditionally viewed as a corpuscle — can be reinterpreted as a wave. Consequently, spacetime exhibits a distributed charge structure.

This interpretation is supported by several experimental observations, notably the scattering of electrons by neutrons, discussed further down the website. While this framework differs from the conventional models of Schrödinger, Heisenberg, and Dirac, it remains mathematically compatible with them.

Schrödinger Orbitals

In the 1930s, two physicists calculated atomic orbitals: Erwin Schrödinger, using wave functions, and Werner Heisenberg, using matrix mechanics. Ultimately, Schrödinger’s model became the accepted framework.

Schrödinger’s wave equation, which bears his name, is one of the cornerstones of quantum mechanics. The equation1 itself is brilliant, mathematically elegant and internally consistent. However, its probabilistic interpretation is not entirely accurate.

Einstein acknowledged the significance of Schrödinger’s equation but, being deeply rational, rejected the Max Born's probabilistic implications. On this topic, he famously declared: “God does not play dice,” meaning that probabilities should not govern the foundations of quantum mechanics.

The Spacetime Model aligns closely with Einstein’s philosophical stance, while also embracing the mathematical structure of Schrödinger’s equation.

1 - This equation is not operational per se. It functions through the insertion of arguments (such as the Hamiltonian) into operators like ∂/∂t. The orbitals are then defined based on the eigenvalues derived from these calculations.

What Is the Wave Model?

Max Born and Schrödinger’s Theory: Let us consider an electron orbiting a nucleus. Suppose this electron is in its corpuscular form and traverses a total of 50 spatial cells (sCells). According to Schrödinger’s equation, the probability of locating the electron in any one of these cells is 0.02 (i.e., 2%). In other words, there is a one-in-fifty chance of detecting the electron in a given sCell: 1/50 = 0.02.

Wave Model: In contrast, the wave model proposes that the electron does not revolve around the nucleus but instead forms a static wave. A kind of cloud of electric charge envelops the nucleus (see the concept of duality). In this framework, the electron in its wave form is distributed across the same 50 sCells. Rather than a single corpuscle with a charge of –1 moving around the nucleus, we now have 50 static sCells, each carrying a fractional charge of –0.02.

Spacetime Model Interpretation

We are thus presented with two distinct interpretations of Schrödinger’s equation, both of which yield identical results. These interpretations can be summarized as follows:

- Schrödinger’s Interpretation: The Schrödinger equation expresses the probability of locating the electron at a specific point in space and time.

- Spacetime Model Interpretation (this work): The Schrödinger's equation reflects the portion of the electron’s electric charge contained within a given sCell at a specific time. This is no longer a probabilistic view, but rather a charge-based interpretation, in which the electron is represented as a cloud of distributed charge enveloping the nucleus, as demonstrated by the principle of wave–particle duality.

Enigma of the Void in Atoms

It may seem surprising to claim that 99.999% of matter is actually vacuum — but this is a well-established fact. Our concept of sCells offers a logical and coherent explanation for this phenomenon.

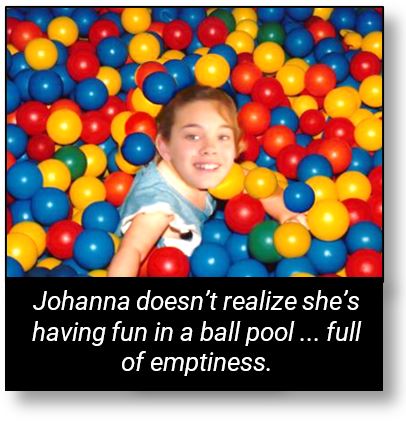

The figure below illustrates a ball pool. Each ball is composed of approximately 99% vacuum (or air), meaning the actual PVC content in each ball is minimal.

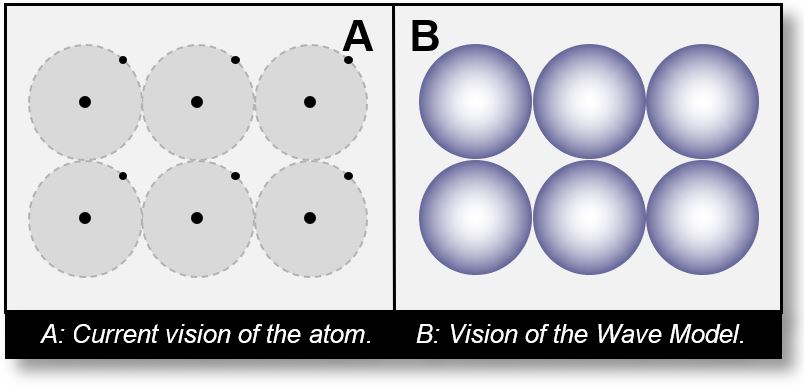

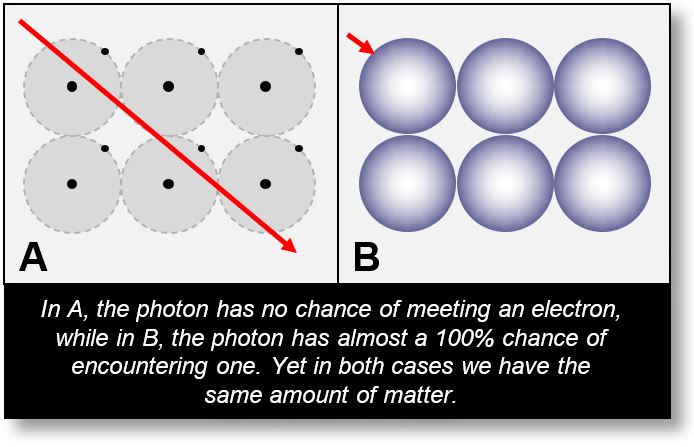

The same principle applies to atoms. Figures A and B below provide a visual comparison between two conceptual models:

- In Figure A, the electron is depicted as a particle orbiting the nucleus. In this view, the atom appears almost entirely empty, making it difficult to visualize any tangible structure.

- In Figure B, the electron is distributed across multiple sCells. Although the total amount of matter remains extremely small (less than 0.001%), we perceive its presence because it forms a kind of shell around the nucleus.

This is analogous to the ball pool: the volume seems substantial, yet it consists mostly of air. Even if the shell of each ball were only a few microns thick, the balls would still be visible.

Confirmation of the Wave Model

Let us first recall the experimental orders of magnitude:

- The diameter ratio between the nucleus and the atom is approximately 1:40,000.

- If the nucleus had a diameter of 1 meter,

- ... the atom would span 40 kilometers,

- ... and the electron’s diameter would be about 8 centimeters.

- In this scale model, the 8 cm electron would orbit the 1 m nucleus at a radius of 20 km.

The atomic image above supports the structure proposed by the Wave Model — namely, that the electron is not a localized corpuscle but is instead distributed around the nucleus as a cloud of electric charge. With such proportions (electron = 8 cm, nucleus = 1 m, orbital radius = 20 km), it becomes virtually impossible to visualize the entire atom. Only the nucleus is visible — if at all ! It is obvious that the electron remains undetectable as a discrete object.

This image therefore aligns far more closely with the Wave Model, in which the electron forms a diffuse shell of charge around the nucleus, than with the traditional corpuscular model of electrons revolving along fixed orbitals.

This image strongly suggests that electrons are distributed across sCells within atoms.

Photoelectric Effect (PE) Enigma

The photoelectric effect, or PE effect, refers to the emission of electrons from an atom under the influence of electromagnetic radiation—typically a beam of light. A photon collides with an electron within the atom and ejects it. These ejected electrons, now considered free, generate the electric current we observe in devices such as solar panels.

However, the PE effect presents a conceptual challenge, as illustrated by the red trajectory of the photon in Figure A below. In current atomic models, the electron is said to orbit the nucleus at a relatively vast distance. So vast, in fact, that the probability of a photon directly encountering the electron is virtually zero.

By contrast, if the electron is distributed across sCells around the nucleus in its wave form, as shown in Figure B, the photon has a 100% chance of encountering part of the electron’s charge cloud.

If the electron is treated as a particle revolving around the nucleus (as in Figure A), the photon has only one chance in billions of billions to interact with it.

Under such conditions,

The current explanation that electrons orbit

the nucleus is incorrect. If it were true, the

photoelectric effect’s efficiency wouldn’t be

as high as 95% but something like 0,00001%.

Note: The photoelectric effect (PE) should not be confused with a similar phenomenon, the Compton effect.

Summary of the Wave Model

Contrary to conventional scientific belief, the electron in an atom does not revolve around the nucleus. Instead, it is distributed throughout the surrounding space, within sCells, in the form of a static wave—a kind of charge cloud. This concept forms the core of our Wave Model, an alternative theory that operates as a subset of the broader Spacetime Model.

The Wave Model does not alter the Schrödinger equation, which remains fully applicable. The key difference lies in interpretation: within our framework, the output of Schrödinger’s equation reflects the actual distribution of electric charge, rather than mere probabilities.

This model is illustrated here through the photoelectric effect, and further evidence will be presented throughout the remainder of this book. As we will see later on, a graph produced by physicists themselves reinforces the credibility of the Wave Model beyond reasonable doubt.