Quarks

What Are Quarks Made Of

In the previous chapters, we assumed that spacetime is divided into discrete units called 'sCells'.

In this chapter, we explore the possibility of generating electrons, positrons, and quarks from sCells. A proposal is presented here to address the issue of quark charges of 2/3 and –1/3.

Quarks

The discovery of quarks was made in 1964 by Murray Gell-Mann (Nobel Prize, 1969) and George Zweig. Back in 1932, when James Chadwick (Nobel Prize, 1935) discovered the neutron, it was believed that this particle was a combination of a proton and an electron. This idea was later abandoned because it conflicted with spin theory.

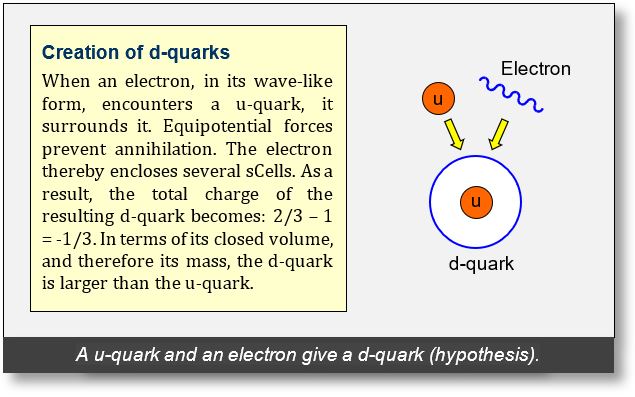

The Spacetime Model, however, maintains that the idea of “Neutron = Proton + Electron” should be preserved, regardless of what spin theory suggests. Similarly, the Spacetime Model considers the d-quark to be a u-quark combined with an electron1.

- Definition of Spin - In truth, no one really knows what spin is. In the 1920s, it was thought to represent the electron rotating around its own axis. Today, it is recognized as a “quantum value,” which essentially means: We don’t know.

- A Risky Extrapolation - Spin works well in the context of atomic orbitals, but it becomes problematic when applied to the nucleus. The fact that a physical law functions perfectly for atoms does not guarantee its validity for nuclei. There is a significant difference between atomic orbitals and the nucleus: orbitals are open volumes, while the nucleus is a closed or hermetic volume (see Part 1). What holds true for atoms does not necessarily apply to nuclei.

- The Proton Spin Crisis - Issues surrounding spin led to the emergence of the “Proton Spin Crisis” in 1987. As noted in the English Wikipedia: “The problem is considered one of the most important unsolved problems in physics.” This statement highlights how obscure and poorly understood the concept of spin truly is.

- Obsolete Laws - Spin was discovered in the 1920s and successfully integrated into quantum mechanics. Laws were then established, including Pauli’s exclusion principle (Nobel Prize, 1945). However, these laws are still applied today. This raises a fundamental question: Can the laws of 1925, developed for atoms, be indiscriminately applied to quarks, which were discovered 40 years later? Clearly, the answer is no. In fact, the first step is to ask the right question:

What exactly is spin?

1. The fact that spin is well defined for fermions and bosons does not imply that spin-statistical theorems (Fermi–Dirac or Bose–Einstein) can be universally applied to all particles. These theorems work well in the context of atoms, but their relevance to quarks remains unverified.

U and d-Quarks

It is for all these reasons that the Spacetime Model does not follow the current view regarding the spin. By applying the principles of the 'Wave Model' to the u and d-quarks, we obtain the figure below.

The outer envelope of the d-quark is composed of an electron that has a dual function:

- It passes the charge of the u-quark from +2/3 to -1/3.

- It increases the closed volume of the assembly, i.e. of the mass (Part 1). This is the cause of the d-quark's mass increase.

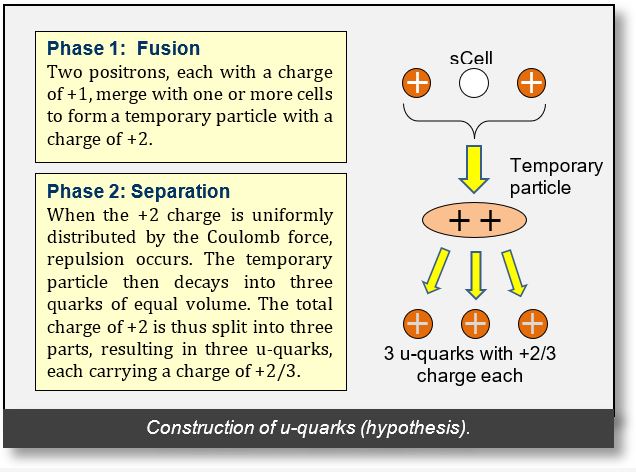

Construction of Quarks - Hypothesis

The figures below present a proposed model for the construction of u and d-quarks. In these diagrams, we assume that sCells, electrons, and positrons share the same closed volume, or “mass” — namely 511 keV/mc2. This is a speculative assumption; the value has not been experimentally verified.

3 u-quarks.......created with 2 positrons

d-quark............u-quark + 1 electron

Gluons

Within atomic nuclei, the positron and the peripheral electron serve an additional role: they act as the agents of the Strong Nuclear Force (see Part 5).

In mainstream physics, it is currently believed that the strong force originates from a distinct particle within the nucleus known as the gluon. The theory describing gluons is called Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD).

In this respect, the Spacetime Model and QCD are aligned: both consider the gluon to be a closed volume contained within a hermetic volume, as described in Part 1. Refer later to the webpage 'Nucleons and Gluons', which provides a detailed description of what the strong force and quarks might be.

Quark Sphericity

If quarks possessed perfect sphericity like protons, their measurements would consistently yield identical values. However, quark measurements typically exhibit a margin of error — except in the case of the top quark (t-quark). This raises an important question: why does such variability exist for quarks, but not for nucleons or electrons?

The Spacetime Model proposes that quarks could have an elongated, “bean-like” shape, which offers a plausible explanation. If this hypothesis is correct, the margin of error would depend on the quark’s orientation during measurement. In a vertical position, the quark might yield one value, while in a horizontal position, it could produce a different one.

This idea appears to be supported by the t-quark (see Part 5), whose mass is precisely measured at 173.34 GeV/c2. You’ll find more details in the later sections of this site.

According to the model, the t-quark is actually a b-quark (mass ≈ 4.2 GeV/c2) enveloped by a positron. The substantial space between the b-quark and its positronic shell tends to regularize the overall shape, resulting in a near-perfect sphere.

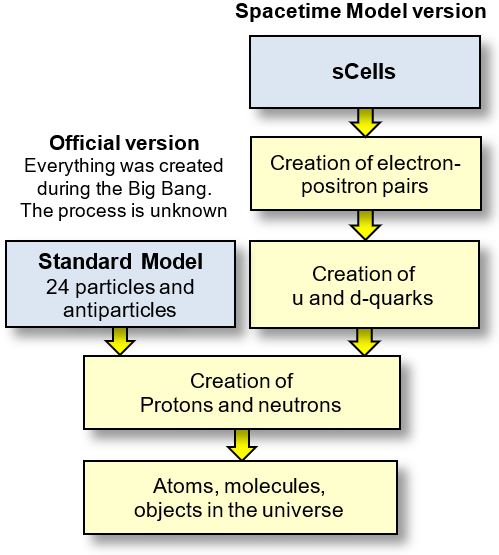

Origin of Quarks (hypothesis)

Understanding Quarks:

A Simplified Summary

- Starting Point. Polarity Gravitational spacetime does not account for polarity. Therefore, a second spacetime is required to manage polarized components. This second spacetime must coexist with the gravitational spacetime described by General Relativity.

- Dual Structure. Everyday elements such as air, water, and others exhibit a dual structure—just like the two spacetimes. For example, air masses can generate depressions while also enabling the propagation of acoustic waves. A dual spacetime structure — gravitational and electromagnetic — is not merely exceptional; it is essential to explain several unresolved phenomena in quantum mechanics.

- Universality in Nature. Nature tends to repeat itself when left undisturbed. Since this dual structure exists on Earth, it is highly probable that it exists throughout the universe.

- Quantization. In nature, everything is quantized: water (via H2O molecules), air, and so on. The electromagnetic spacetime would therefore also be quantized into cells—called sCells—likely comparable in size to electrons (to be verified), but without electric charge.

Electrons and Positrons. An sCell can transfer all or part of its charge to an adjacent sCell, thereby creating an electron–positron pair.

u and d Quarks. The electrons and positrons thus generated give rise to u and d quarks. Two positrons are required to create three u quarks.

Protons and Neutrons. The u and d quarks are captured by peripheral electrons. The space between the peripheral electron and the quarks forms a closed volume known as a gluon. This volume is hermetic (see Part 1).

Atoms, Molecules, and Beyond These u and d quarks, electrons, protons, and neutrons subsequently combine to form all known elementary particles, atoms, and molecules.