Antimatter in the Universe

Where is Antimatter in the Universe?

The prevailing view among physicists is that the universe’s birth produced equal amounts of particles and antiparticles, balancing positive and negative charges. Yet, this symmetry appears broken: antimatter is conspicuously absent.

For over a century, scientists have sought to understand where the missing antimatter went.

Our previous deductions about quarks and the wave model lead us to a rational explanation of the location of antimatter in the universe.

Starting Point

The positron, or positive electron, was discovered in 1932 by Carl Anderson, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1936.

As the antiparticle of the electron, the positron is a form of antimatter. Given that the universe is thought to be composed of electron–positron pairs — two fundamental particles — we can draw two key observations:

- Localization within atoms. If the Big Bang produced electron–positron pairs simultaneously and at the same location, then positrons should be extremely close to electrons. Electrons, as we know, occupy atomic orbitals. Consequently, positrons cannot be far away. The only plausible location for them within the atom is inside the nucleus — specifically, embedded within u- and d-quarks. It would be strange to assume that electrons and positrons were created together, yet ended up billions of light-years apart.

- β⁺ Radioactivity. Certain atomic nuclei emit positrons — antimatter — through a process known as β⁺ radioactivity. In these cases, positrons escape from the nucleus, implying they originate from known particles. Whether we refer to these particles as bosons, gluons, u-quarks, d-quarks, or even hypothetical entities like X, Y, or Z, it is reasonable to infer that antimatter resides within them. Indeed, β⁺ radioactivity serves as a powerful clue in identifying where antimatter exists in the universe. This strongly suggests that the search for antimatter should begin within the atomic nucleus—not in speculative ‘parallel universes’ linked by hypothetical wormholes.

There is greater chance of finding antimatter in nuclei rather than in these "parallel universes"

Searching for Positrons

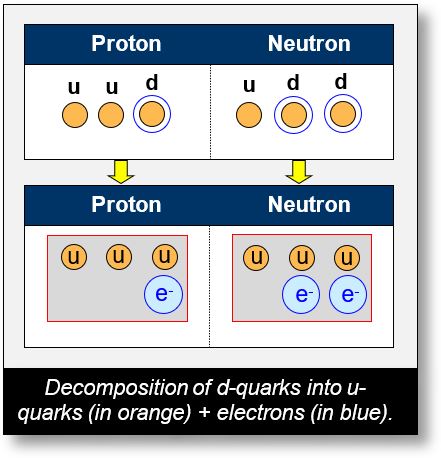

We’ve seen how quarks can be constructed from electrons and positrons. In this section, we’ll take it a step further by examining the internal structure of protons and neutrons — not from the perspective of quarks, but from the electrons and positrons that constitute them.

It’s important to remember that two positrons are needed to form three up quarks, and that adding an electron produces a down quark. Note: This hypothesis requires experimental validation.

The top part of the figure on the previous page shows protons and neutrons as they are typically detected. The bottom part illustrates the same quark composition, but with the electron separated. The three up quarks are shown in orange, and the electrons in blue.

- Proton: (u u d), equivalent to 3 up quarks + 1 electron,

- Neutron: (u d d), equivalent to 3 up quarks + 2 electrons.

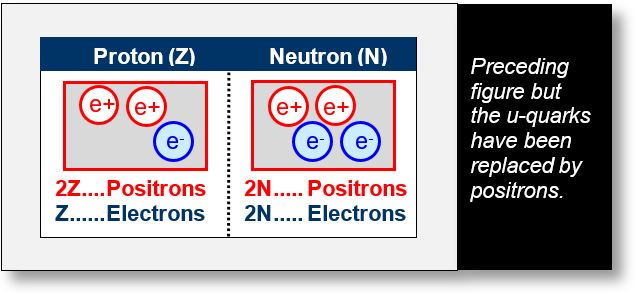

Since two positrons are sufficient to generate three up quarks, the three up quarks in each nucleon (highlighted in orange in the previous figure) can be replaced by two positrons. In the figure below, positrons are circled in red, and electrons in blue.

The figure below uses the same components as the one above, but includes the number of atomic electrons — that is, electrons in the orbitals — in the third column.

Recall that in any basic chemical element, there are Z protons, N neutrons, and Z electrons.

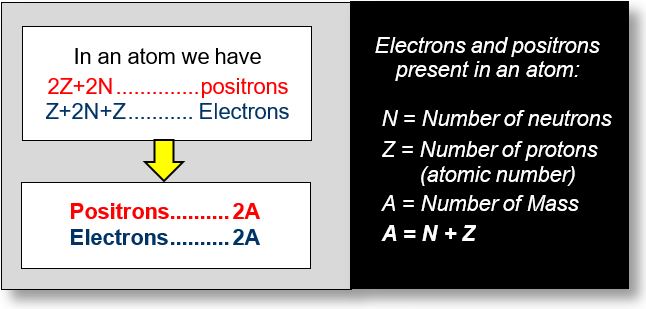

Finally, the electrons and positrons are arranged as shown in the figure on the following figure.

Finally, the electrons and positrons are arranged as shown in the figure on the following figure.

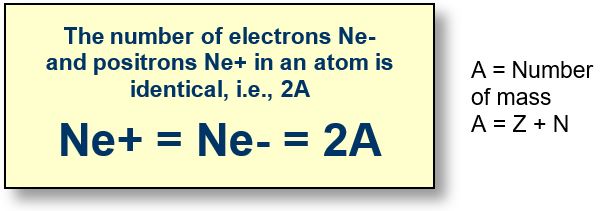

Thus, regardless of the chemical element considered, this calculation suggests that every atom contains the same number of positions as electrons — namely, 2A, where A is the mass number. Consequently, all the antimatter in the universe may be embedded within atoms themselves.

This conclusion aligns with the formalism of Richard Feynman (Nobel Prize, 1965) and with Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD), in which the electron and positron play perfectly symmetric roles within quantum mechanics.

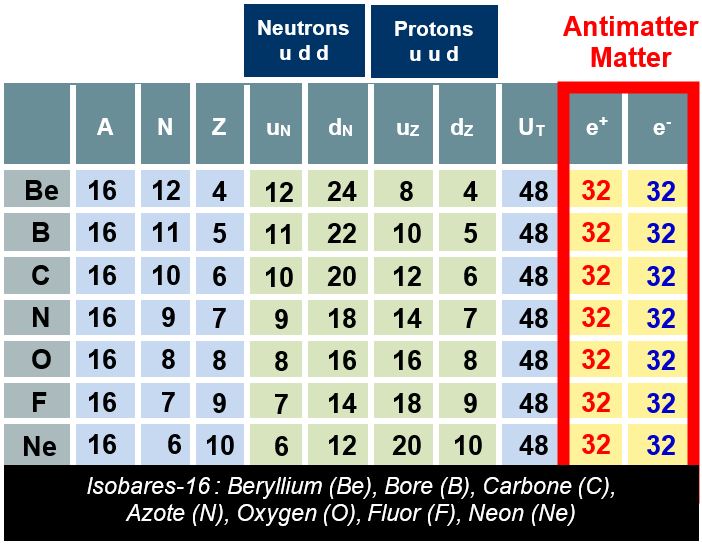

Example with Isobaric Nuclei

The table below displays some A=16 isobars. The first three columns indicate the characteristics of the chemical element in question. The other columns are interpreted as follows. Please refer to the table below.

Neutrons (u d d) → N:

- uN = Number of u-quarks in neutrons, i.e., N,

- dN = Number of d-quarks in neutrons, i.e., 2N.

Protons (u u d) → Z:

- uN = Number of u-quarks in protons, i.e., 2Z,

- dN = Number of d-quarks in protons, i.e., Z.

Total u-quarks in the nucleus:

- The subtotal of u-quarks is: uN + uN,

- The subtotal of the u-quarks contained in the d-quarks is : dN + dN. Just a reminder that a d-quark is a u-quark with a peripheral electron.

- uN = uN + uN + dN + dN

Total number of positrons e+ in the nucleus:

To create three u-quarks, two positrons are required, i.e.

e+ = 2/3 uN

Total number of electrons e- in the atom:

Each d-quark contains an electron. In addition, there are Z atomic electrons present in the atom. Thus, the total number of electrons in the atom is

e- = dN + dN + Z

Here, we demonstrate that the number of positrons equals the number of electrons, regardless of the atom considered. Matter and antimatter are thus perfectly balanced.

In all cases and for all atoms, the total number of electrons and positrons is equal to twice the mass number A. In other words, this suggests that the antimatter humanity has been searching for over the past century is, in fact, embedded within nucleon quarks.

What is remarkable is that this result holds true for all known atoms. There is only one exception among the 2,930 atomic configurations: lithium-3 (³Li).

This exception possesses a unique characteristic that reinforces our 'Wave Model' theory rather than contradicting it. The explanation is provided below.

The Li-3 Exception

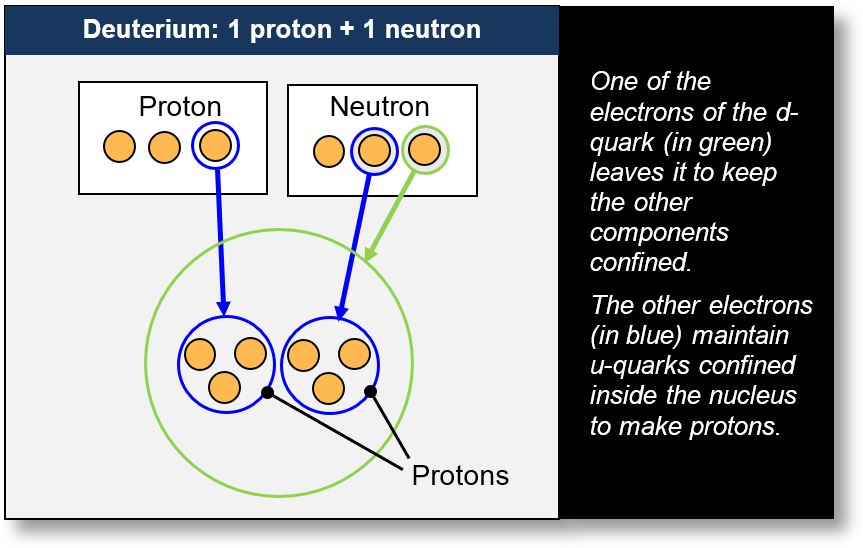

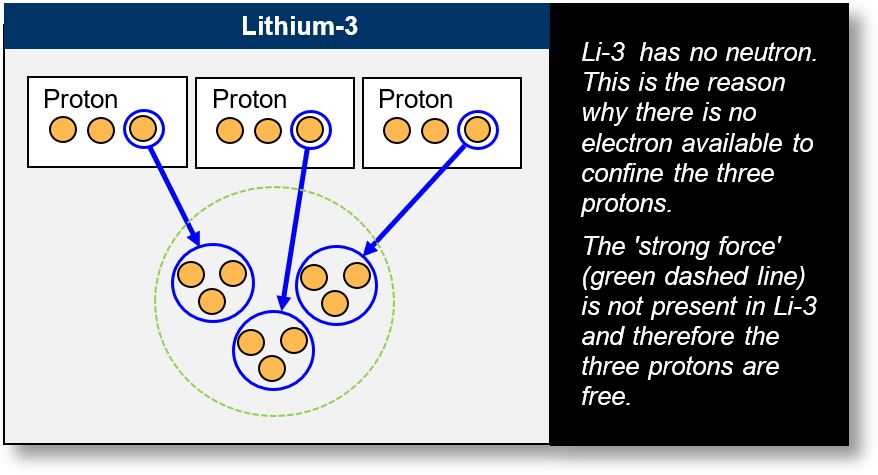

The only nucleus that does not follow this rule is lithium-3 (Li-3). This nucleus has a unique characteristic: it contains no neutrons. To understand this peculiarity, we can refer to a simple example — deuterium (see the figure below). Deuterium is an isotope of hydrogen composed of one proton and one neutron.

- Proton: The proton in deuterium, like any proton, consists of two up quarks (u) and one down quark (d). According to the model, a down quark is formed by a combination of an up quark and an electron (shown in blue in the figure). This electron, in its wave-like form, captures and confines the three up quarks. This confinement is what we refer to as the strong nuclear force, which will be explained in more detail later.

- Neutron: The neutron in deuterium, like any neutron, is composed of one up quark and two down quarks (the up quarks are circled in blue and green in the figure). Since each down quark is made of an up quark and an electron, the neutron contains a total of three up quarks and two electrons. One of these electrons (in blue) is used to confine the three up quarks into a proton-like structure.

As a result, the nucleus effectively contains two protons (blue) and one electron (green). This electron acts as a binding agent, trapping the other components of the nucleus and functioning as a manifestation of the strong nuclear force.

Lithium-3: A Unique Case

The figure below illustrates lithium-3. Its nucleus consists of three protons. Since each proton contains one down quark (d-quark), we have a total of three electrons (shown in blue) — and no more.

These electrons are used to confine the up quarks (u-quarks)1 in order to form protons. However, unlike in the case of deuterium, there is no additional electron available to bind the three protons together within the Li-3 nucleus (indicated by the green dotted outline). As a result, the three protons remain unbound, making lithium-3 highly unstable.

This conclusion is precisely what experimental observations confirm.

Li-3 is highly unstable because it has no neutron,

a fact verified by experiments. This unique case helps confirm the Spacetime Model theory.

1. The hydrogen nucleus is a similar case, but the electron associated with the d-quark is sufficient to prevent the u-quarks from dispersing.

Antimatter in the Universe

Based on current knowledge, hydrogen, neutrons, and various atoms constitute the primary components of the universe. Black holes and dark matter are excluded from this analysis, as their exact composition remains unknown.

- Neutrons: We have demonstrated that the neutron exhibits a perfect equivalence between matter and antimatter.

- Hydrogen and other atoms: Hydrogen consists of a proton and an electron. The proton is composed of three quarks: two up quarks (u) and one down quark (d). If we decompose the down quark into an up quark and an electron, the proton becomes (u u u)e⁻. The triplet (u u u) corresponds to a configuration formed by two positrons. Thus, the total composition is equivalent to two positrons and one electron. Additionally, we must account for the atomic electrons present in the orbitals. For hydrogen, this leads to the relation: Ne+ = Ne- = 2A, where A is the mass number.

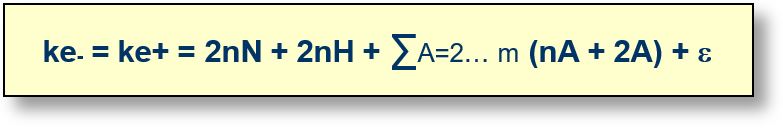

Definitions:

ke-, ke+: Total number of electrons and positrons in the universe.

nN: Number of neutrons present in various elements.

nH: Number of hydrogen atoms in the universe, excluding isotopes, which are accounted for in the following terms.

Index A: Atomic number of the various atoms in the universe. The upper limit m represents the maximum atomic number considered. The index A starts from 2, since hydrogen (A = 1) has already been treated separately.

nA: Number of atoms with atomic number A in the universe.

2A: Number of electrons or positrons associated with an atom of index A.

ε: Free particles in various forms (e.g., muons) present in the universe. This quantity is considered negligible (pending verification) compared to the other terms in the equation.

In the universe, matter (electrons) and antimatter (positrons) exist in equal amounts.

Bethe Cycle – CNO Cycle

Stars are initially composed of hydrogen. Under extreme pressure and temperature, hydrogen undergoes nuclear fusion (see Part 1), gradually transforming into heavier chemical elements such as carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen as the cycle progresses. Other fusion pathways also exist, such as the proton–proton chain.

The Bethe cycle — also known as the CNO cycle (Carbon–Nitrogen–Oxygen) — describes the transformation of specific isotopes, primarily C-12, C-13, N-13, N-14, N-15, and O-15, through a series of nuclear reactions that power stars. This mechanism was theorized by Hans Bethe, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1967.

Conclusions Concerning Antimatter

We have seen that antimatter is inevitably created in the immediate vicinity of matter. In other words: “Where there is an electron, there must be a positron.” It is not plausible that matter (electrons) exists on Earth while its antimatter counterpart (positrons) is located in distant galaxies. Their coexistence is local and intrinsic to atomic structure.

- Matter is necessarily very close to antimatter.

- This implies that electrons are near positrons.

- The only location where positrons can be found within the atom is inside the nucleus, embedded in the quarks.

- The deduction is therefore: antimatter necessarily resides within the quarks.

Summary of Antimatter

- Antimatter in the universe is not hidden in parallel worlds connected by hypothetical "wormholes," but is present before us—embedded within up quarks (u-quarks).

- The number of electrons in an atom is equal to the number of positrons.

- This number corresponds to twice the atom’s mass number. That is, if an atom has a mass number A, it contains 2A electrons and 2A positrons—representing 2A units of matter and 2A units of antimatter.

- The explanation provided in this webpage regarding lithium-3 (Li-3) supports the two theoretical frameworks proposed in this book: the Spacetime Model and the Wave Model.

- Positrons and up quarks are fundamentally identical. Although their configurations and charges differ, they share the same intrinsic nature. In both cases, they are charged sCells.