Standard Model (of Physics)

What is the "Standard Model"?

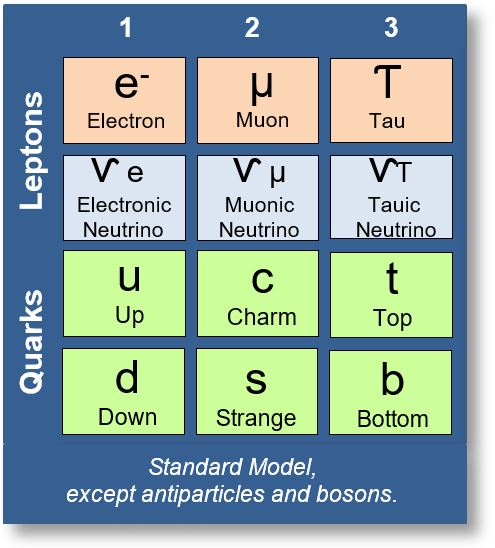

The Standard Model of particle physics is the most successful theory we have for describing the fundamental building blocks of the universe and their interactions, except gravity. It’s often compared to a periodic table for quantum physics, but focused on subatomic particles.

In this webpage, we’ve added a supplement on neutrinos, a topic that remains highly controversial within the framework of the Spacetime Model.

Additionally, the Standard Model is closely linked to the Big Bang theory. While we briefly mention this connection here, the topic will be explored in greater depth at the end of the site.

The Standard Model

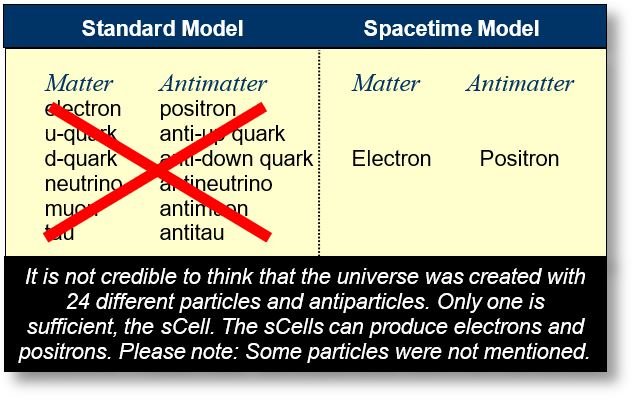

Grouping the main elementary particles into a "Standard Model" is a sound approach — except for neutrinos, which arguably do not belong here. However, it is not logical to assume that the entire universe was created solely through the Standard Model.

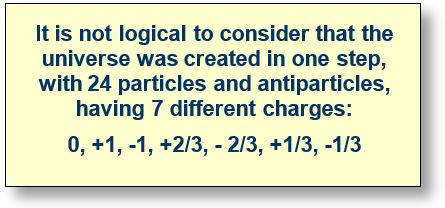

The particles and antiparticles of the first group are currently considered the "building blocks" of the universe. This classification yields seven distinct charges: –1, –2/3, –1/3, 0, +1/3, +2/3, and +1. This perspective is not shared by the Spacetime Model, which finds it implausible. Indeed, it seems highly unlikely that such a wide variety of particles with so many different charges could have given rise to the universe at the same time. In contrast, electrons and positrons — referred to as sCells — are more than sufficient to explain its creation.

Consider life on Earth: it likely began with cells of a single type1. Living cells emerged, and Darwinian evolution eventually led to the millions of species we know today. A similar reasoning may apply to the universe. It likely began with a single particle and its antiparticle — not 24 particles. This idea is explored further in Part 5.

1 It is widely believed, though not yet confirmed, that RNA was the first molecule capable of replication. This molecule is thought to have appeared on Earth around 3.5 billion years ago.

Neutrinos in the Current Standard Model

The Standard Model includes both neutrinos and antineutrinos. However, we do not share this perspective. That’s why we believe it’s important to revisit the origin of these two particles.

In reality, the neutrino does not exist independently — it is produced during specific interactions. There are three types of neutrinos:

- Electronic neutrinos, which originate from electrons.

- Muonic neutrinos, which stem from muons — a type of high-mass electron, approximately 207 times heavier than the electron.

- Tauic neutrinos, which derive from taus — an even more massive electron - like particle, about 2,288 times heavier than the electron.

Neutrinos in the Spacetime Model

In the Spacetime Model, the properties of neutrinos are not those of the Standard Model. The differences are:

- Origin: Neutrinos appear to be a residual wave emitted during an interaction. For example, during e+/e- annihilation, the antineutrino produced would be a piece of a positron or electron. Therefore, it is not appropriate to include them in the Standard Model.

- Mass: It would be logical to think that the mass of the neutrino or antineutrino is equal to the difference in the masses of the particles, which are at the origin of the interactions. However, the masses of electrons and positrons are known with good precision but not enough to be able to relate them to neutrinos. On the other hand, this mass must be calculated according to the methods given in Part 1. It is not a simple matter of subtraction.

- Charge: The neutrino charge is currently at zero. If the neutrino comes from charged particles, it should have a low charge of the same polarity as the larger particle. It means that the charge of the neutrino should not be zero.

- Spin: The spin will be seen later, in part 4.

- Neutrino oscillations: This is a phenomenon in which a neutrino changes category. It is normal to observe fluctuations in the signal (jitters) at different points along the route under certain conditions. Electronic engineers have known about this phenomenon for a long time.

Neutrino Charge

Physicists generally consider that particles carry either an integer electric charge, such as –1, 0, or +1, or fractional charges in multiples of 1/3, as observed in quarks.

To date, no electric charge has been detected in neutrinos. However, neutrino experiments are notoriously challenging and often require substantial resources. Therefore, the absence of observed charge does not definitively prove that neutrinos are electrically neutral.

According to the Spacetime Model, neutrinos are predicted to possess an infinitesimal electric charge.

In the case of an electron–positron (e⁺e⁻) annihilation, the possible charge of the resulting neutrino could be expressed as:

q = (Ma - Mb)/Ma 1.602 x 10-19 C

where:

- q is the neutrino’s electric charge, in coulombs,

- Ma, Mb represent the closed volumes (interpreted as mass) of the electron and positron, with Ma being the larger of the two.

: The mass calculation must be performed using the revised method based on volumes rather than conventional mass (see Appendix A2 for details).

Conclusions on Neutrinos

It is far more plausible to assume that the neutrino carries a charge — even a minimal one — than to suggest it emerges from nothing. In quantum mechanics, as elsewhere, spontaneous creation does not occur without cause.

Moreover, Feynman diagrams appear to support the perspective of the Spacetime Model. As mentioned earlier, these diagrams depict the neutrino as being generated from either the electron or the positron.

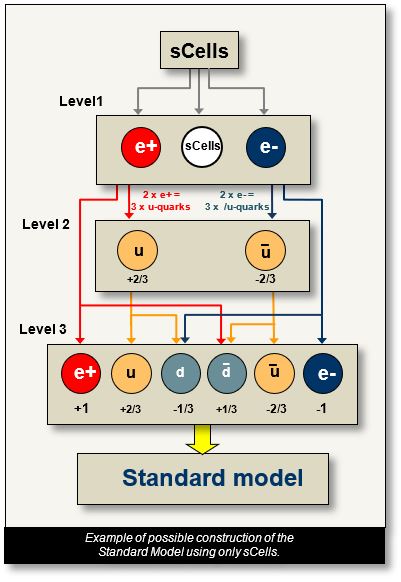

Construction of the Standard Model

This chart shows that it is possible to construct the Standard Model using only sCells. In this table, neutrinos and antineutrinos are not mentioned. There is no reason for neutrinos, which are fragments of electrons and positrons, to be part of the Standard Model.

Creation of the Universe

This topic will be explored in detail in Part 5. We briefly address it here because, in modern physics, many physicists consider the particles of the Standard Model to be at the origin of the Big Bang — that is, the creation of the universe. However, this idea cannot be upheld for several reasons:

- The Big Bang theory suggests that the entire universe emerged from a region of Planck length, no larger than the head of a pin. From the perspective of the Spacetime Model, such a claim lacks any scientific foundation and amounts to pure science fiction.

- In any creative process, complexity arises from simplicity. Physics must adhere to the same principle. It is illogical to assume that the universe was created in a single step from 24 particles (+ bosons); this number is far too large for an initial state.

- The genesis of the universe involves a mystery known as the “enigma of the electron” (see Part 5). This enigma cannot be resolved within the framework of the Standard Model.

Consequently, the Standard Model cannot be considered the origin of the universe.

Summary of the Standard Model

The Standard Model, as accepted by the physics community, is composed of four fundamental particles: the electron, the up quark (u), the down quark (d), and the neutrino (represented by the Greek letter ⱱ).

Each of these particles has a corresponding antiparticle: the positron, the anti-up quark, the anti-down quark, and the antineutrino.

These particles and antiparticles are organized into three groups: 1, 2, and 3. The few particles mentioned above belong to Group 1.

Although this classification is formally correct, two major reservations arise concerning neutrinos and the origin of the universe.

The organizational chart presented earlier offers a more credible framework. It demonstrates how, using sCells, one can generate the full range of fundamental particles and antiparticles required to construct the Standard Model.