The Paradox of Photons

What Is a Photon?

Understanding Light’s Quantum Nature

We previously examined the behavior of electromagnetic (EM) waves. In this webpage, we will delve deeper into the topic.

Max Planck, awarded the Nobel Prize in 1918, was the first to propose that nature is composed of quanta, discrete, non-continuous units. This revolutionary idea enabled Einstein to explain the photoelectric effect in 1905.

The spacetime model builds on the work of Max Planck and Einstein, thanks to the concept of wave–particle duality. Here, we aim to address a fundamental question: Is light a wave or a particle?

The Wave Packet

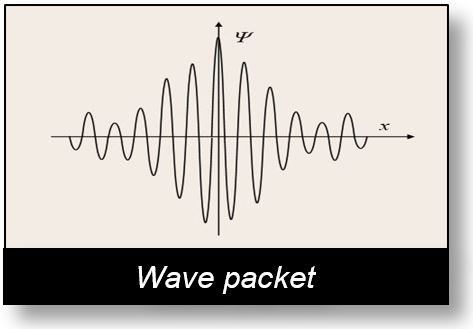

To date, the photon is often described as a "wave packet".

Among the various representations, one is illustrated in the figure below. The Spacetime Model arrives at nearly the same conclusions, though it does so with certain reservations.

The Photon as a Particle

Before we proceed, let’s highlight some of the inconsistencies associated with viewing the photon as a particle:

- Violation of causality: The photon raises a puzzling question — how can electromagnetic radiation seemingly “predict” future interactions?

- Constant speed: Why does the photon always travel at exactly 300,000 km/s, never faster or slower?

- Lack of mass: What explains the photon’s complete absence of mass?

- Inability to stop: Why is it impossible for a photon to come to rest?

- Unclear constitution: What is the photon actually made of?

These unresolved questions suggest that the particle-based concept of the photon contains several ambiguities and conceptual gaps.

The Photoelectric Effect

In 1905, when Einstein explained the photoelectric effect (PE effect) using Planck’s quantum theory, the structure of the atom was still unknown. As previously mentioned, Rutherford at the time envisioned the atom as a “plum pudding,” with electrons embedded like raisins in a diffuse positive charge.

Einstein attributed the low efficiency of the PE effect to the low probability of a photon encountering an electron. It was only later that physicists demonstrated that electrons are not only vastly smaller than atomic nuclei but also located at considerable distances from them.

This implies that the likelihood of a direct collision between a photon and an electron is virtually zero. Yet paradoxically, with the advent of nanotechnology, the efficiency of the photoelectric effect has now surpassed 99%. This remarkable increase remains puzzling if the photon is considered a particle, since such high efficiency would be unexpected given the near-zero cross-section for interaction.

The Photon as a Wave Packet

If we consider the photon not as a corpuscle but as a wave packet, many inconsistencies are reduced. However, several conceptual puzzles remain unresolved:

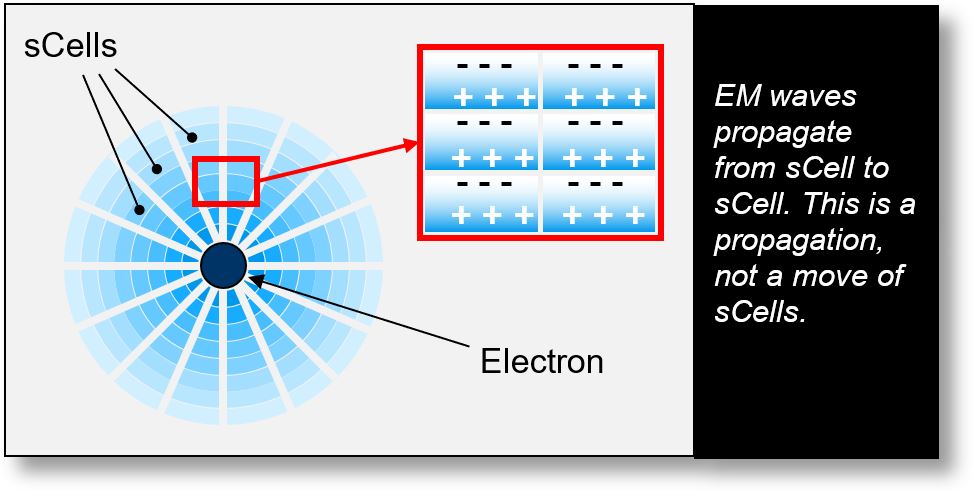

- Propagation Medium: Quantum mechanics currently does not specify the nature of the medium through which electromagnetic (EM) waves propagate. The standard response — "EM waves propagate in a vacuum” — while technically correct, remains vague. It fails to define the underlying structure that enables propagation. The Spacetime Model offers a resolution: EM waves propagate from sCell to sCell within an electromagnetic spacetime that coexists alongside gravitational spacetime.

- Emission of a Wave Packet: Experimental evidence shows that EM waves are emitted omnidirectionally — radio antennas being a prime example. This raises a key question: What mechanism transforms these 360° concentric waves into localized wave packets (photons)? Furthermore, at a given distance x from the emission point, what causes the emergence of a sharply focused angle, characteristic of a wave packet?

- Constant Speed: Why does the photon — or wave packet — always travel at a constant speed of 300,000 km/s in a vacuum? This question was already addressed in part 2.

In summary, conceptualizing the photon as a wave packet resolves several issues inherent in the particle model. Yet, some fundamental aspects still require clarification and deeper theoretical development.

Quantum Waves

The figure below illustrates how electromagnetic (EM) waves propagate from one sCell to another.

At large distances from the emission source, the electric charge contained within an sCell may become too weak to propagate into adjacent sCells. This threshold is, in fact, a quantum limit.

For example, on Earth, water behaves as a quantum medium, as discussed earlier. At first glance, water appears to be continuous. However, it is composed of H2O molecules — discrete units, or 'quanta'. If we disregard atoms, nucleons, and quarks, the quantum of water is the H2O molecule itself.

What happens when a wave encounters a situation where the electric charge is too low to be transmitted from one sCell to the next? What occurs when the sCell quantum threshold is reached? The wave faces only two possible outcomes:

- The electric charge vanishes entirely, and the wave ceases to exist. This scenario must be rejected, as in nature, nothing is created from nothing, and nothing disappears entirely.

- The electric charge remains grouped. The wave continues to propagate, maintaining its coherence as a 'wave packet'. This outcome is more plausible for a simple reason: it is the only viable alternative.

Example: Understanding the Quantum Wave

Nature, when left undisturbed, tends to repeat itself. The following example offers a rational and intuitive way to grasp what a quantum wave is.

Imagine a flat surface covered by a thin layer of water. Using a suitable technical device, we gradually reduce the thickness of this layer. Eventually, we reach a point where it can no longer be thinned — this limit corresponds to the size of an H2O molecule. At that stage, the layer stops spreading, but it does not vanish. Its persistence is certain.

The propagation of a wave follows a similar principle. At great distances from its point of emission, the wave ceases to spread uniformly in all directions (360°) because it reaches a quantum threshold. However, it does not disappear.

This phenomenon is what we refer to here as a "Quantum Wave".

The life cycle of a wave unfolds in three stages: emission, propagation, and reception. In quantum mechanics, the term wave packet — though technically precise — is typically reserved for the reception phase. That is why we propose a broader term: Quantum Wave, which encompasses all three stages of the process: transmitting, propagating, and receiving.

Steps of a Quantum Wave

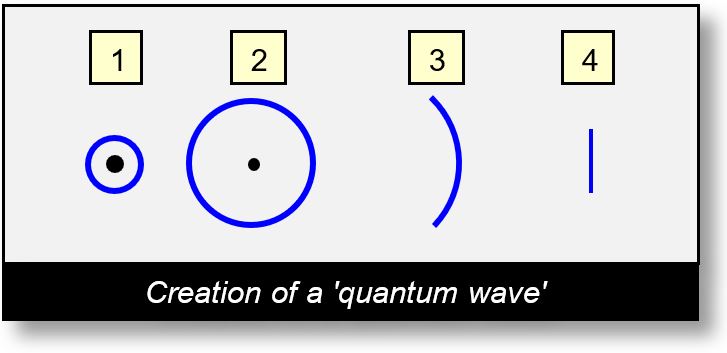

Over long distances, the evolution of an electromagnetic (EM) wave unfolds in distinct stages:

- Step 1 - Emission: The wave is initially emitted in all directions, forming a 360-degree spatial cone. The angle may vary depending on the source and medium. This emission is omnidirectional or broadly distributed.

- Step 2 - Propagation: The wave continues to propagate outward, spreading across space. Its intensity decreases with distance, following the classical 1/r2 law of EM radiation.

- Step 3 - Quantum Threshold: At a certain distance from the source, the energy density of the wave becomes too low to propagate from one sCell to the next. This threshold corresponds to the quantum limit — analogous to the minimal thickness of water in the earlier analogy. At this point, the wave can no longer spread uniformly. It exits the full 360° propagation cone and remains grouped, forming a large arc segment rather than a full circle.

- Step 4 - Quantum Wave Formation: As the distance increases further, the total charge remains constant, but the arc length shortens. The wave becomes increasingly collimated, approaching a straight-line segment. This is the Quantum Wave — a coherent group of sCells that no longer disperses but remains bundled together. It resembles what quantum mechanics calls a wave packet.

Example : Suppose a wave is emitted with 1000 charged sCells distributed over 360°. After traveling x light-years, these 1000 charges are still present, but they are no longer spread over a full sphere. Instead, they remain grouped in a narrow arc or segment. The wave persists, but its dispersion halts at the quantum threshold. It becomes a wave packet — a stable, coherent structure.

Thus, when we observe a distant galaxy, we are not detecting a single photon, but rather a packet of waves that has propagated across billions of years while remaining grouped.

We will now outline the distinct phases of a quantum wave:

- Emission,

- Propagation,

- Reception

Emission

EM radiations are always

emitted as waves*

* Keep in mind that, because of wave–particle duality, a particle inherently propagates always as a wave.

Propagation

The waveform of the radiation remains unchanged at the moment of emission. It appears to be a continuous wave, but in reality, it consists of discrete charges propagating from sCell to sCell in all directions.

At a certain distance, the quantum threshold may be reached. When this occurs, the wave can no longer continue to diminish. An 'ordinary wave' is then transformed into a 'quantum wave'. Distance is the determining factor: beyond a specific range, the wave no longer spreads over 360°, but instead propagates within a very narrow angle — this is what we refer to as a wave packet.

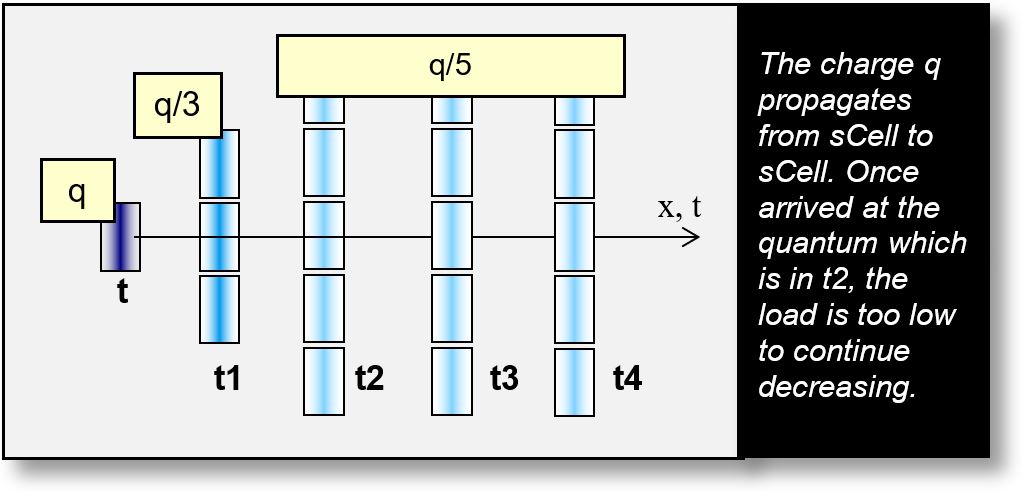

The figure above illustrates an EM wave propagating progressively from sCell to sCell. The initial charge, q, is first divided into three parts, then into five. The quantum threshold q/5 is reached at time t2 in the diagram.

Beyond t2, the EM wave no longer decreases — not because it chooses to, but because it physically cannot. This is analogous to our earlier example: once the water layer reaches the thickness of a single H2O molecule, it cannot become thinner. The sCells reach their quantum limit at t2, t3, and t4. Initially spreading over 360°, the wave stops decreasing and continues to propagate as a wave packet across multiple sCells.

Reception

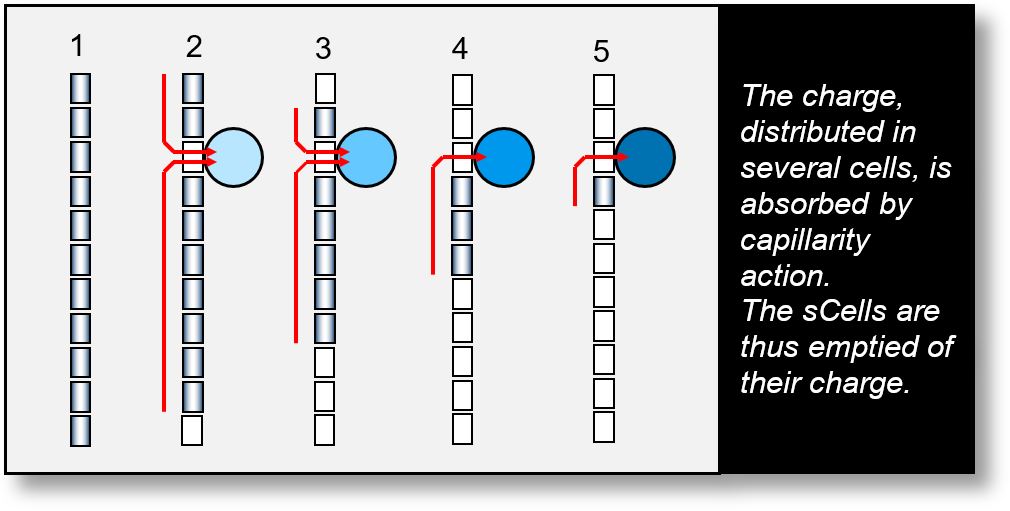

An interaction occurs when an sCell containing part of the total wave encounters an atom or a molecule. Following this contact, the sCell loses its charge and progressively drains adjacent sCells that also carry the wave. This process resembles a well-known phenomenon on Earth: capillarity.

- Phase 1: The EM wave propagates across multiple sCells.

- Phase 2: It encounters an element capable of absorbing its energy. The sCell in contact is discharged. This interaction can occur at any location.

- Phases 3 and 4: The wave continues to be absorbed. The surrounding sCells lose their charge one after another.

- Phase 5: The EM wave is nearly fully absorbed by the interacting element.

Although the EM wave retains its wave-like configuration throughout this process, the receiving element (represented by the blue circle in the figure above) behaves as if it has absorbed a photon. From the experimenter's perspective, it appears that a photon has been captured.

The electromagnetic wave is absorbed at

the point of measurement, creating the

illusion that it consists of discrete photons.

Quantum Waves: Blotting Paper Analogy

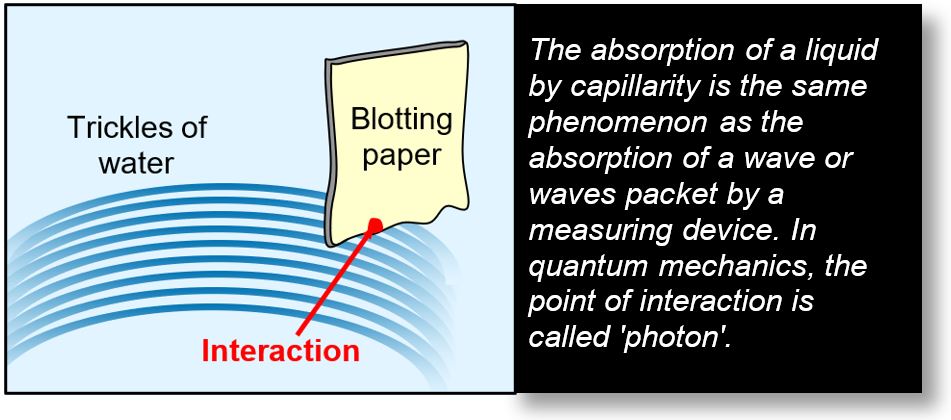

The following example illustrates the mechanism of electromagnetic (EM) wave absorption.

In this analogy, the EM wave is represented by a trickle of water absorbed by blotting paper. The point of interaction (marked by a red dot) corresponds to the location where absorption occurs — that is, where the water first contacts the paper.

In quantum mechanics, when an EM wave encounters a medium capable of absorbing it — such as an atom — an interaction takes place. From the experimenter's perspective, it may appear that a photon has been captured. However, this is merely the point at which the wave, or wave packet, is absorbed.

As soon as we try to measure a wave,

it disappears, because the measuring

device absorbs it on contact.

Mathematical Aspect of the Photon

As previously stated, the photon is a mathematical construct, analogous to a vector. There is therefore no objection to referring to the photon as the point of interaction between the wave and the receiver.

It is important to emphasize that the photon, understood as a particle, does not exist. What actually reaches the receiver are wave packets — quantum or otherwise — not the corpuscular entities traditionally labeled as photons.

Moreover, as discussed at the beginning of this chapter, the particle-based interpretation of the photon is riddled with inconsistencies. The quantum wave framework presented in this article offers coherent explanations for many of the enigmas in quantum mechanics. The resolution of multiple conceptual puzzles is unlikely to be mere coincidence.

Understanding the photon as a quantum wave interaction point is clearer and more accurate than the traditional view of it as a discrete particle.

The earlier phases, emission and propagation, are not encompassed by the standard wave packet model.

Note: While the term wave packet is technically accurate, it applies only to the third phase—reception.

The Experimenter

Imagine being aboard a boat in the middle of the sea. Suddenly, the vessel begins to shake. From inside, it's impossible to determine whether the disturbance was caused by a passing wave or a collision with a marine animal.

This scenario serves as an analogy for quantum mechanics: the electromagnetic (EM) wave corresponds to the sea wave, while the corpuscle represents the marine animal.

In quantum mechanics, the experimenter faces a similar uncertainty. Upon detecting an event, they cannot definitively say whether they have observed a photon, a wave packet, or merely the point of interaction of a quantum wave. What is perceived as a photon may, in fact, be nothing more than the localized absorption of a wave. The true nature of the interaction remains elusive.

The experimenter believes they have detected a photon. In reality, what has been measured

is the point at which the electromagnetic

wave interacts with the measuring device.

Summary of How Photons Work

Emission

EM radiation is emitted as a wave that propagates spherically outward from its source, forming a 360° emission pattern in three-dimensional space (with some exceptions, however).

- At short distances

- The wave propagates with an intensity that decreases proportionally to 1/r2.

- At long distances

- The intensity continues to decrease as 1/r2, but once the wave reaches a quantum threshold, its energy density becomes too low to sustain further dispersion.

- The wave cannot vanish entirely — according to physical principles, nothing disappears without a trace. The charges within the wave remain grouped.

- Beyond this threshold, a quantum wave forms: a wave that propagates while remaining coherently clustered.

- This clustered wave can persist and travel across billions of years without dispersing.

Reception

When the EM wave encounters a medium capable of absorbing it, the following process unfolds:

- The sCell at the point of interaction discharges its energy into the absorbing element — be it an atom, molecule, or other structure.

- Neighboring sCells are drained of their charge through a capillary-like mechanism.

- Ultimately, the wave is absorbed at the interaction site.

Summary

From emission to reception, the wave remains coherently grouped. Upon encountering an absorbing medium, such as an atom or molecule, it is absorbed via a kind of capillary action.

When the experimenter registers a detection, they instinctively interpret it as the capture of a photon. In reality, what has been measured is simply the point of interaction — the localized absorption of a quantum wave.