Electromagnetic Waves

Rethinking Electromagnetism

Significant discoveries have been made in recent decades in the field of electromagnetism, particularly regarding coherent light sources such as lasers. Yet, the fundamental nature of a simple light ray — or electromagnetic (EM) wave — remains poorly understood.

One of the most persistent challenges in physics is the wave–particle duality. This paradox was addressed in Part 2. Building on that insight, we now propose a new interpretation of the photon and the underlying mechanisms of electromagnetism.

EM vs. Matter Waves

There are two distinct types of waves: electromagnetic (EM) waves and matter waves.

- EM waves are oscillations of electric and magnetic fields that propagate through space,

- Matter waves, predicted by de Broglie, describe the wave-like behavior of particles such as electrons.

Although both exhibit different wave properties, matter waves are not electromagnetic in nature.

We have previously explored this topic. In this chapter, we introduce sCells as a conceptual tool to deepen our understanding of these wave phenomena.

The following experiment illustrates the emission of EM waves resulting from changes in atomic orbitals. These transitions involve variations in charge over time, expressed as Δq/Δt.

imagine you're in a bathtub. If you suddenly close your hand underwater, a wave propagates across the surface. This wave results from a rapid displacement of water, creating eddies that carry energy. The faster you close your hand, the more energetic the disturbance — just like in physics, where the rate of change influences the energy transmitted.

If your hand closes slowly, the water adjusts gradually, and no significant wave forms. This illustrates a key principle: waves carry energy, and that energy depends on how quickly the change occurs — in other words, on the time factor, such as the period or frequency.

This concept parallels the expression Δq/Δt, which represents the rate of change of charge over time. In atomic systems, rapid transitions between energy levels (such as orbital changes) produce electromagnetic waves, with their energy directly linked to time of transition, i.e. to the frequency.

Strictly speaking, matter waves are not electromagnetic (EM) waves. While both exhibit wave-like behavior, they originate from different physical phenomena. Physicists primarily distinguish them by the nature of the particles involved, particularly their intrinsic spin. EM waves are associated with particles that have integer spin — such as photons with spin 1 — and are classified as bosons. Matter waves, on the other hand, describe particles like electrons or protons, which have half-integer spin and are known as fermions. For more details on spin and its implications, please refer to the webpage concerning the spin.

Explanation of EM Waves

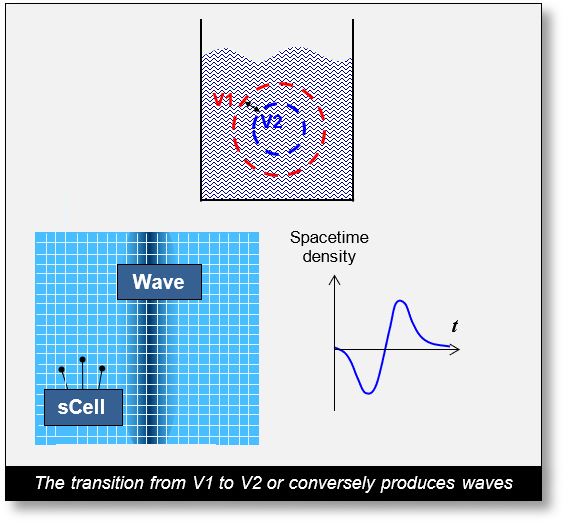

A second example is illustrated in the figure below.

A perforated balloon is immersed in a container filled with water. The holes allow water to flow freely into and out of the balloon. When its volume changes from V1 to V2 — or vice versa — a wave is generated in the surrounding fluid. Despite the perforations, the total amount of water remains unchanged.

This is because the eddies produced in the water are bipolar in nature: regions of increased pressure are followed by regions of decreased pressure, and vice versa.

Similarly, when waves propagate through neutral sCells, they undergo alternating phases of compression and rarefaction — experiencing successive high and low pressure zones.

Basics of Matter Waves

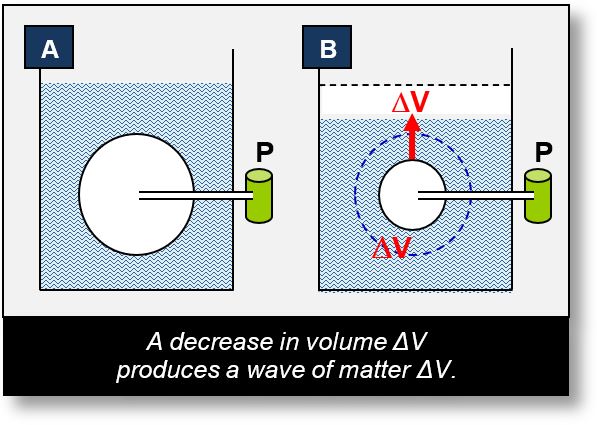

Picture a balloon immersed in a container filled with water (Fig. A below). Using pump P, a vacuum is created inside the balloon (Fig. B):

- The balloon’s volume rapidly decreases by an amount ΔV.

- This sudden change generates eddies in the surrounding water, each carrying the same volume ΔV.

- When the wave reaches the surface, it reconverts into a volume ΔV — identical to the initial decrease.

This simple experiment illustrates the transformation of a localized volume change into a propagating wave — and vice versa. Nothing is lost, nothing is created. Importantly, we refer to volume, not mass (see Part 1).

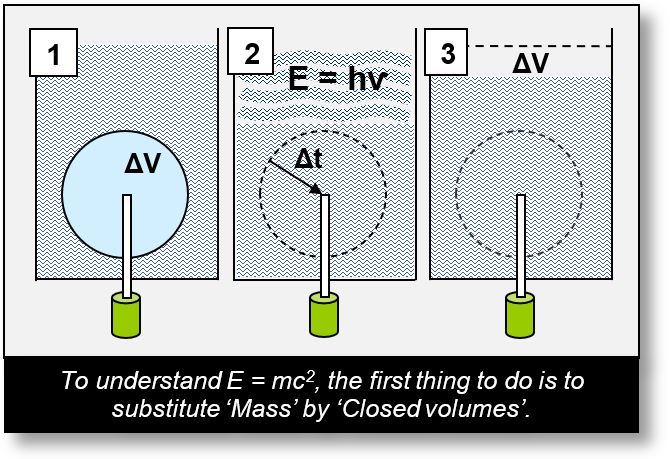

This principle underlies the mechanism of the atomic bomb1. In the famous equation E = mc2, E represents the energy produced, while m is traditionally interpreted as mass. This view is conceptually misleading. In this context, m should be understood as the closed volume (or volume with mass). As shown in the figure, it is the volume that changes — not the mass. The relation m = f(closed volume) is detailed in Appendix A2.

1In the atomic bomb, the volume change ΔV produces high-intensity electromagnetic (EM) waves, primarily in the form of gamma rays.

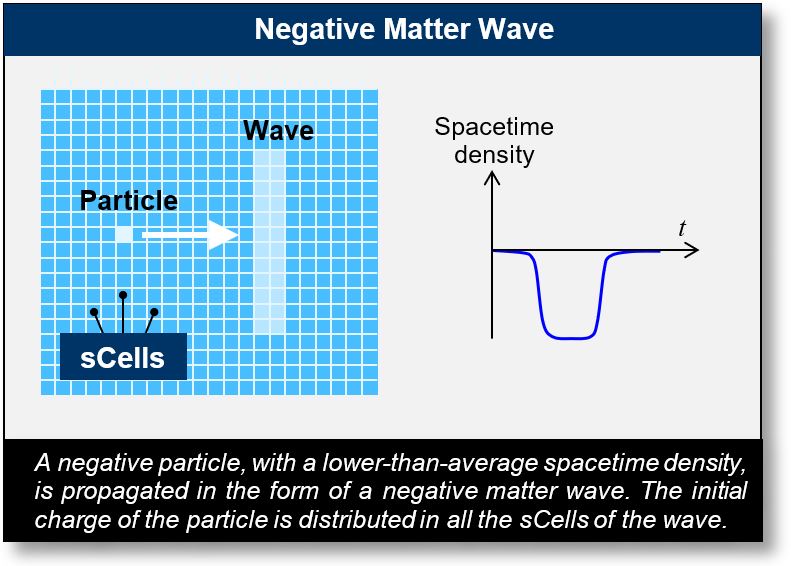

Explanation of Matter Waves

The two figures below show waves of matter, both negative and positive. Like EM waves, these charges are propagating from sCell to sCell. Their spacetime density is higher (positive waves) or lower (negative waves) than the average.

Clarification on Wave Propagation It is evident that waves — whether bipolar or matter waves — do not move in the way we often imagine. What occurs is propagation, not displacement. This process unfolds through the attraction and repulsion of charges, transmitted from one sCell to the next. A common misconception arises from confusing the notion of “movement” with “propagation.”

Example: Place a ruler flat on a table. If you push it from the right end, the left end responds instantly. However, it’s not the right end physically traveling to the left at a speed v. Instead, a mechanical disturbance spreads through the ruler. This is not a displacement of material, but a transmission of force.

Waves behave similarly. The sCells themselves do not travel from point A to point B. Instead, charges propagate through the sCells at a speed of approximately 300,000 km/s, driven by alternating forces of attraction and repulsion.

As previously discussed, this propagation speed is governed by the permittivity and permeability of spacetime.

EM–Matter Wave Differences

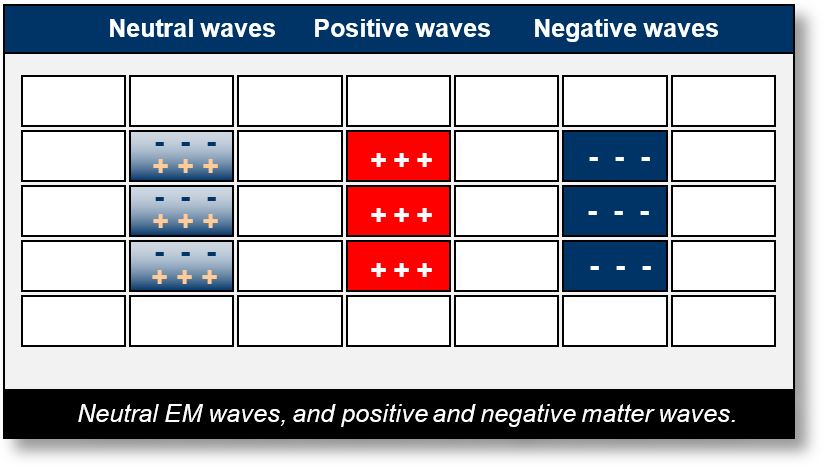

The distinction between electromagnetic (EM) waves and matter waves lies solely in the nature of the charge within the sCells, as illustrated in the figure below.

- sCells: In this figure, sCells are depicted as empty rectangles. These represent regions of spacetime that contain no charge — they are entirely neutral.

- EM (neutral) waves: These sCells are shown as blue gradient rectangles (on the left), each containing a pair of opposite charges: +++ and –––. Although the total charge is zero, the distribution within each sCell is not uniform. Each sCell consists of a positive and a negative region, making it electrically neutral overall. Regardless of how the charges are arranged internally, the wave propagates through attraction and repulsion from one sCell to the next, at a speed of approximately 300,000 km/s. Recall the earlier demonstration with a magnet and five nuts — it illustrates this principle clearly. The net charge remains neutral throughout the propagation.

- Matter waves: In this case, each red or blue sCell temporarily acquires an additional charge (+ or –). This extra charge also propagates from sCell to sCell at the same speed of 300,000 km/s. The figure below shows sCells carrying both positive and negative charges, indicating localized deviations from neutrality.

E = hν

This formula shows that the energy of a wave does not depend on the number of photons received, but rather on the frequency of the incident radiation. Although this may seem counterintuitive, it reflects a fundamental physical reality.

The bathtub experiment described earlier offers a helpful analogy. Reposition your hand in the water as instructed, and close it quickly. The amplitude of the resulting eddy depends on how fast your hand moves. The faster the motion, the greater the energy transferred to the water.

Light behaves similarly. Its energy is given by the simple equation E = hv, where h is Planck’s constant and v (Greek letter nu) is the frequency of the radiation. Just as in the bathtub experiment, a faster change — represented here by a higher frequency — results in greater energy.

Annihilation e+e-

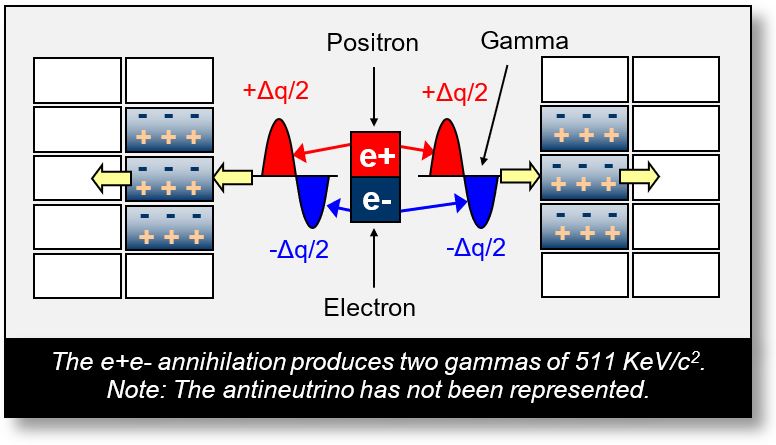

How can mass be transformed into two gamma rays — that is, into two waves? This question was addressed in Part 2 of this book, where we discussed electron–positron annihilation. The figure below offers an additional explanation using the concept of sCells.

In this scenario, both the blue and red squares are stationary.

- When an electron encounters a positron, the excess spacetime associated with the positron compensates for the spacetime deficit of the electron. The resulting sCell becomes neutral, yielding two neutral sCells.

- The positron’s charge transitions from +1 to 0, and the electron’s from –1 to 0. This results in a double Δq/Δt — represented by two half-sinusoids.

- The annihilation of e+e- generates eddies in spacetime.

- These eddies gradually propagate through adjacent sCells (depicted as +++ and – – – in gradient blue).

- Electromagnetic radiation propagates from sCell to sCell in the form of an EM wave, due to its bipolar nature.

- These EM rays are gamma rays, each carrying an energy of 511 keV/c2, assuming the initial particles are at rest.

- If a gamma ray passes near a nucleus and the energy conditions are favorable, it can split into two components — one negative and one positive.

- In this way, the wave becomes a particle once again.

As we can see, the e⁺e⁻ annihilation process, when interpreted through the lens of sCells, is both simple and logically coherent.

Dimensional Quantity

Let us revisit a topic previously discussed.

According to Einstein, the universe is four-dimensional (4D), described by two fundamental types of dimensions: spatial lengths [L] — namely x,y, and z — and time [T]. Another variable, mass [M], is also widely used in physics.

However, the dimensional quantity [M] is not an intrinsic part of the 4D spacetime framework. In the Spacetime Model, mass can be expressed as a function M = f(x,y,z,t), as detailed in Appendix A2. This formulation allows us to remain within the 4D structure.

Although [M] is not a fundamental dimension of the universe, we will continue to use it in the following sections for educational clarity and convenience.

Mass and Energy

It is incorrect to claim that mass is energy. In fact, the dimensional quantity of mass,[M], differs from that of energy, which is [ML2/T2]. The famous equation E=mc2 can be broken down as follows:

Right-hand side: The speed of light, 𝑐, has the dimension [L/T]. Squaring it yields [L2/T2]. When mass [M] is multiplied by c2, the resulting dimensional quantity is [ML2/T2]—which corresponds to energy.

Left-hand side: The dimensional quantity of energy E is also [ML2/T2].

Since both sides of the equation E=mc2 share the same dimensional structure, the equation is said to be homogeneous.

In other words, a mass — or more precisely, a closed volume (see Part 1)—can produce energy. However, it is incorrect to equate mass with energy directly. Saying “Mass = Energy” implies [M]=[ML2/T2], which is dimensionally inconsistent and therefore invalid.

E = mc² (Using Volumes)

This formula may seem obscure at first. However, Part 1 has already introduced a conceptual framework. Here, we delve deeper into the topic.

The process illustrated in the figure below unfolds as follows. Its quantum mechanical equivalent is indicated in green:

Step 1: A balloon is filled with air. It remains motionless and does not produce energy (the particle is at rest).

Step 2: The balloon deflates over a time interval Δt (the closed volume of the particle disappears, similar to e⁺e⁻ annihilation). This reduction in volume generates eddies in the surrounding water (analogous to the emission of gamma rays and EM/matter waves in spacetime).

These waves propagate through the water (through spacetime), carrying the energy released by the deflation of the balloon. In both cases, the energy of the wave is given by the relation E = hν.

Step 3: When the waves reach the surface, they are reconverted into a volume (a gamma ray can produce an e⁺e⁻ pair — two closed volumes. See Part 1).

It is important to note that energy only manifests in phase 2, when the volume is in its wave state. In phases 1 and 3, where the volume behaves as a corpuscle, energy exists solely as potential energy — that is, as latent energy.

To summarize, the formula E = mc2 can be interpreted as follows:

- Wave–particle duality (see Part 2) explains how particles can transform into waves and vice versa. In this model, particles and waves are fundamentally the same: charged sCells.

- In Part 1, we established a relationship between mass and closed volume, which is mathematically defined in Appendix A2 of the book.

- Energy is released when the closed volume of a particle disappears.

- The formula E = mc2 is indeed used — but it applies to closed volumes, not directly to mass (as clarified in Part 1).

Summary - Electromagnetic Waves

This webpage explores the relationship between waves and sCells.

To understand the origin of energy in the equation E = mc2, we must revisit its conceptual foundations. The explanation proceeds as follows:

- A particle is modeled as a closed volume (see Part 1).

- When this closed volume disappears, it generates eddies — i.e., waves — in spacetime.

- These waves carry energy, described by the relation E = hv.

- This energy can be reconverted into mass — or more precisely, into closed volumes — via E = mc2.

- Thus, particles transform into waves and can return to particle form.

This explanation is pedagogical in nature. In reality, the process described by E = mc2 involves the emission of various forms of radiation, which in turn trigger multiple types of activation1.

1Activation is a process by which, under the influence of external radiation or during an interaction, an atom transforms into another atom — typically one that is radioactive.