Waves, Photons, Duality...

Applications of Electromagnetism

This page addresses four major enigmas in quantum mechanics. The first two have remained unresolved for over a century:

- Young’s double-slit experiment (1801),

- Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle,

- The EPR paradox and quantum entanglement,

- The violation of causality.

Young’s Slits – Description

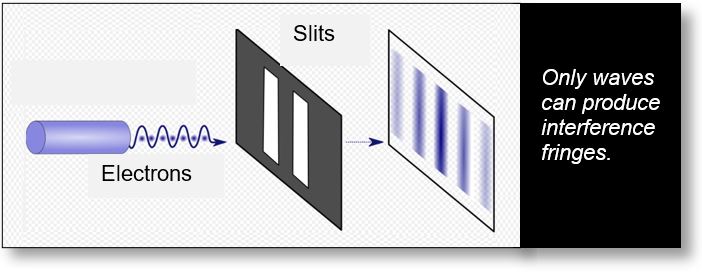

Light or particles are emitted from a source and directed toward a barrier with two slits. On the screen behind the slits, a diffraction pattern appears — an alternating series of light and dark fringes.

This pattern indicates that the light or particles behave as waves, since only waves can produce such interference fringes. Classically, photons are expected to pass through one slit or the other, not both simultaneously. Therefore, if they were purely particles, no interference pattern would emerge.

In this experiment, Young’s slits were used not only with light but also with electrons. The result was surprising: in both cases — whether using light or particles — the same interference pattern appeared. This suggests that particles such as electrons also exhibit wave-like behavior, just as Louis de Broglie proposed and as confirmed by the experiments of Davisson and Germer.

Young’s Slits – Enigma

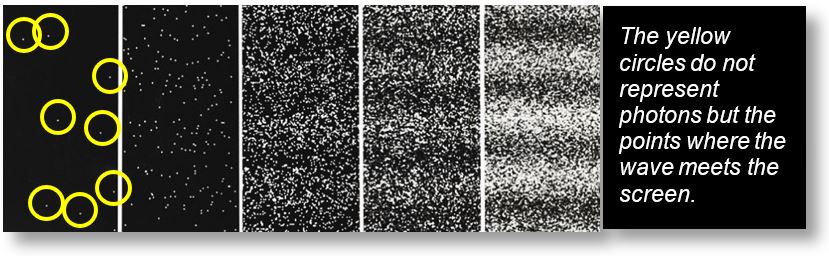

The photo below shows an experiment conducted photon by photon. The interference fringes only appear after the screen has received a large number of photons.

But how can these interference fringes be explained? A single photon cannot pass through both slits at the same time. Logically, this experiment — based solely on individual photons — should not produce any interference pattern.

In academic physics, this phenomenon is "explained" by a theory known as Superposed States. However, the Spacetime Model does not adopt this complex interpretation. Instead, it offers a much simpler, more logical, and more rational explanation, presented below.

Young’s Slits – Explanation

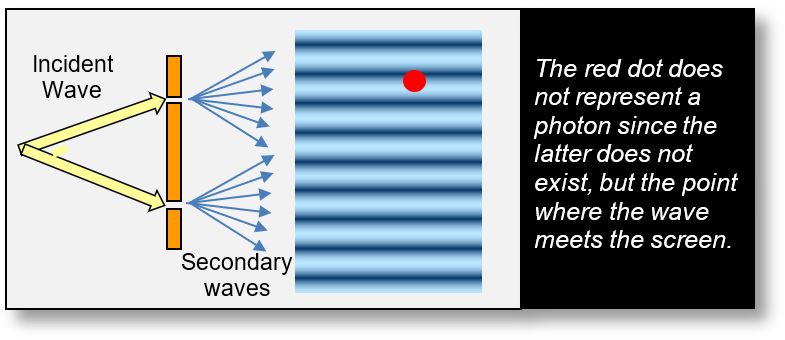

An electromagnetic (EM) wave is emitted toward the two slits, as illustrated in the figure below.

The edges of each slit are composed of atoms, and according to Einstein’s general relativity (Part 1), a gravitational field exists near each edge — even if extremely weak, it is nonetheless present.

This gravitational field bends the surrounding spacetime. As a result, the wave does not travel in a straight line through each slit. Instead, it follows curved paths influenced by the local geometry — similar to Von Laue’s A–A′ geodesic described in Part 1.

Thus, the incident wave is subtly deflected near the slit edges, contributing to the formation of the interference pattern observed on the screen.

The incident wave produces two beams of secondary waves (blue arrows). The trajectory of each secondary wave varies depending on its proximity to the edge of each slit.

Variations in path length lead to

interference effects, resulting from

phase differences between the waves

The first wave that encounters a molecule on the screen interacts with it (red dot). The sCells of the secondary wave that have interacted with the screen molecule are then instantly discharged. This occurs via capillarity at a speed of 300,000 km/s.

Thus, the red dot does not represent a photon, but rather the initial point of contact between the secondary waves and the screen. It creates the illusion for the experimenter of having detected a photon. In reality, what has been detected is the point at which a secondary wave is absorbed by the screen’s molecules.

The experimenter believes he has detected a

photon, whereas he has actually observed the

point of impact of a secondary wave on the screen

The absorption speed is so high that it is extremely unlikely for a wave to activate two molecules simultaneously. A delay of just a few picoseconds is enough to prevent a double detection. Measuring a wave causes it to vanish, as it is immediately absorbed by the screen’s molecules.

Young's Slits – Validation (for physicists)

The probability that a wave produces two distinct impacts is extremely low. In such cases, it is reasonable to assume that the wave’s energy is divided between the two interactions. For instance, a gamma ray of 511 keV/c2 passing through both slits could be detected as two separate gamma rays of 211 keV/c2 and 300 keV/c2. A high-performance coincidence detection system can readily reveal this phenomenon by analyzing the energy distribution. The use of a crystal detector can further enhance measurement accuracy. These experiments are relatively simple to perform and cost-effective, making them suitable for validating the Young’s Slits interpretation proposed here.

Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle – Description

This principle was formulated by Werner Heisenberg (Nobel Prize, 1932). It states that there is a fundamental limit to the precision with which two physical properties of a particle — such as its position x and momentum p — can be known simultaneously.

The issue is that the origin of this phenomenon remains unexplained. Existing theories, such as the superposition of states, describe its consequences but do not account for the underlying cause of the uncertainty relation.

However, as we will see, this apparent mystery is in fact quite simple to understand.

For physicists: Initially, it was introduced as a simple principle. Later, a formal mathematical derivation was developed. As a result, the original term Heisenberg uncertainty principle has gradually been replaced by the more precise expression Heisenberg "uncertainty relation".

Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle – Explanation

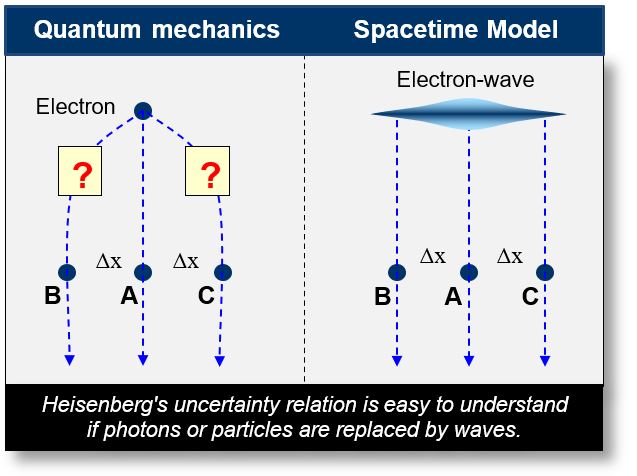

Current Theory in Quantum Mechanics: Consider a highly precise device that directs electrons toward point A (see figure below, left side). According to Heisenberg’s uncertainty relation, the electron may be detected at points A, B, or C. Although this phenomenon is real, it remains conceptually puzzling.

Proposed Theory of the Spacetime Model: The work of Louis de Broglie, Davisson, and Germer, along with the wave–particle duality, clearly shows that particles propagate as waves rather than as discrete corpuscles. Consequently, points A, B, and C are not traversed by photons, but by waves.

When an electron-wave reaches the measuring device, an interaction occurs — as previously described. The Cells are then emptied via capillarity. On the right side of the figure below, most of the wave is absorbed at point A, but occasionally, smaller portions are detected at points B or C. Just as in the Young’s slits experiment, the experimenter believes they have detected photons. In reality, they have observed a wave with varying amplitudes at A, B, and C.

There is no need to invoke probabilities here. The process is straightforward, logical, and grounded in common sense.

EPR Paradox – Description

Entanglement is a phenomenon in which two particles form a correlated system. Any action performed on one particle instantaneously affects the other, even if they are separated by several kilometres. This can be likened to a kind of “thought transmission” between particles.

Below is a simplified summary of the EPR Paradox (Einstein, Podolsky, and Rosen), to which physicist Alain Aspect (Nobel Prize, 2022) made significant contributions.

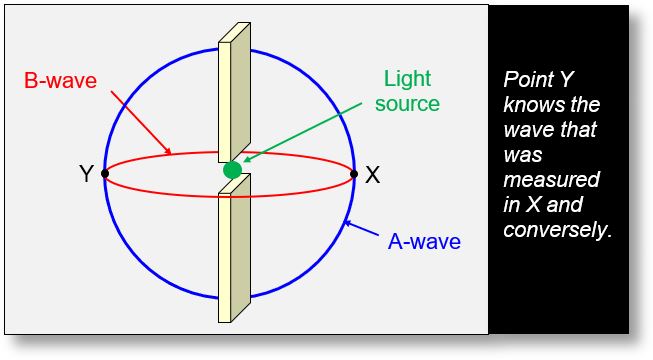

An electromagnetic (EM) wave is emitted (in green). Wave A (in blue) is vertically polarized, while wave B (in red) is horizontally polarized.

Definition: If a horizontal polarization (red) is measured at point X, then a vertical polarization (blue) will be measured at point Y — and vice versa. In short, point Y will always register the complementary polarization to that measured at point X.

But how can point Y “know” the polarization measured at point X? We will attempt to provide a rational explanation for this enigma known as the EPR Paradox, though these interpretations must still be experimentally validated.

EPR Paradox – Explanation

To understand the EPR paradox, one must replace the notion of photons with that of classical and/or quantum waves. Light is emitted by the source in wave form and propagates through electromagnetic (EM) spacetime.

If point X measures a vertical polarization (blue), all wave components carrying this polarization are absorbed by the measuring device and vanish through capillarity. The horizontal polarization (red) remains unaffected.

Similarly, if point X measures the horizontal polarization (red), all corresponding wave components are absorbed and disappear via capillarity, while the vertical polarization (blue) remains intact.

Even if the two measuring instruments, X and Y, are separated by a concrete or metal wall, the wave persists because it propagates through EM spacetime, which permeates all regions. Up to this point, the behavior remains rational.

However, if the two measurement points are located far from the emission source, the EPR anomaly should no longer occur. In such cases, the initially emitted 360° EM waves transform into quantum EM waves — also known as wave packets — with a much narrower angular spread. The system is no longer entangled.

In the context of quantum waves, the EPR anomaly

is expected to vanish when the measurement

points are sufficiently separated in space.

Violation of the Causality Principle

We conclude with a particularly intriguing enigma in quantum mechanics. The Sun emits light radiation toward the Earth. Eight minutes later, we receive it. But what exactly are these radiations composed of?

Photons? If the radiation is captured by solar panels, it behaves as photons — more precisely, as wave packets. This is consistent with Einstein’s photoelectric effect, which shows that only photons can trigger an electric current in photovoltaic cells.

Waves? If the radiation passes through a prism, it behaves as a wave. Only waves can be decomposed into the visible spectrum, producing the colors of the rainbow.

This dual behavior raises a fundamental question: how can the same radiation exhibit both particle-like and wave-like properties depending on the measuring device? It challenges our classical understanding of causality and invites a deeper reflection on the nature of light and measurement.

Causality Principle – Explanation

QUESTION: How can the Sun “know” whether the radiation it emits will encounter a solar panel or a prism? How could it possibly “predict” whether its radiation should behave as waves or as photons (wave packets)?

Now imagine that, during the 8-minute journey from the Sun to Earth, the experimenter changes their mind and replaces the solar panel with a prism. By what mysterious mechanism could the Sun adapt its radiation accordingly — switching from waves to photons or vice versa?

Since photons do not exist in this model, the radiation emitted by the Sun is always composed of waves. These waves travel the 8-minute distance in wave form. It is possible that the traditional 360° wave gradually transforms into a quantum wave (a wave packet) if the Earth–Sun distance justifies such a narrowing.

So we observe:

- Prism: When the radiation reaches the prism, it is dispersed into the colors of the rainbow. No absorption occurs.

- Solar panel: When the radiation reaches the solar panel, it is absorbed and converted into electrical energy.

The point of interaction — analogous to the red dots in previous figures — resembles a photon. It behaves like a photon, carries the characteristics of a photon, and is interpreted as a photon, but it is not a photon. The experimenter believes he has detected a photon, whereas in reality he has observed the point of contact between the wave and the solar panel.

Summary of key

Applications of Electromagnetism

To fully understand electromagnetism, we must set aside the concept of photons and instead consider waves — or more precisely, quantum waves. It is worth noting that physicists already tend to replace photons with wave packets. What remains missing, however, is a comprehensive explanation of the entire process, including the role and functioning of sCells.

At the moment of measurement, the wave is absorbed by capillarity through the molecules located at the point of interaction. The sCells are then discharged, and the wave vanishes. The absorption point may resemble a photon, exhibit the characteristics of a photon, and be interpreted as a photon — but it is not a photon.

The experimenter believes they have detected a photon, when in reality, they have observed the interaction point between the wave and the measuring device — ultimately, a quantum wave.