Atoms Revisited

Atoms and the Wave Model Explained

We return to the topic of atoms to explore some of their specific characteristics.

Orbitals: Much has been said about atomic orbitals since 1925. The Schrödinger equation remains a powerful tool, offering highly accurate calculations. However, the probabilistic interpretation of orbitals still warrants deeper investigation.

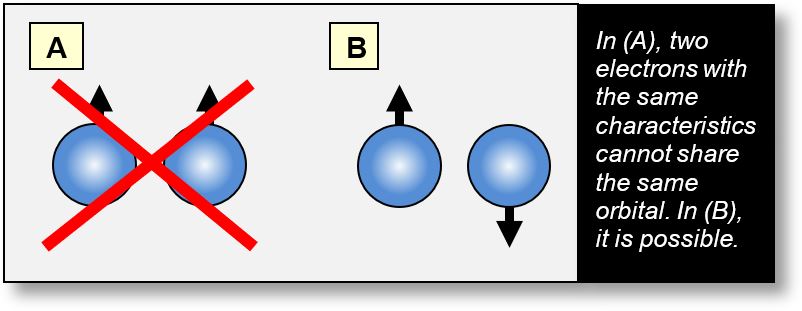

Pauli Exclusion Principle: In current quantum mechanics, the Pauli principle lacks a fully rational explanation. In this section, we propose a plausible and coherent alternative.

Historical Background

Ernest Rutherford (Nobel Prize, 1908) proposed that electrons orbited the nucleus in a continuous, corpuscular motion. However, around 1925, the notion of probability emerged as a foundational concept in atomic theory.

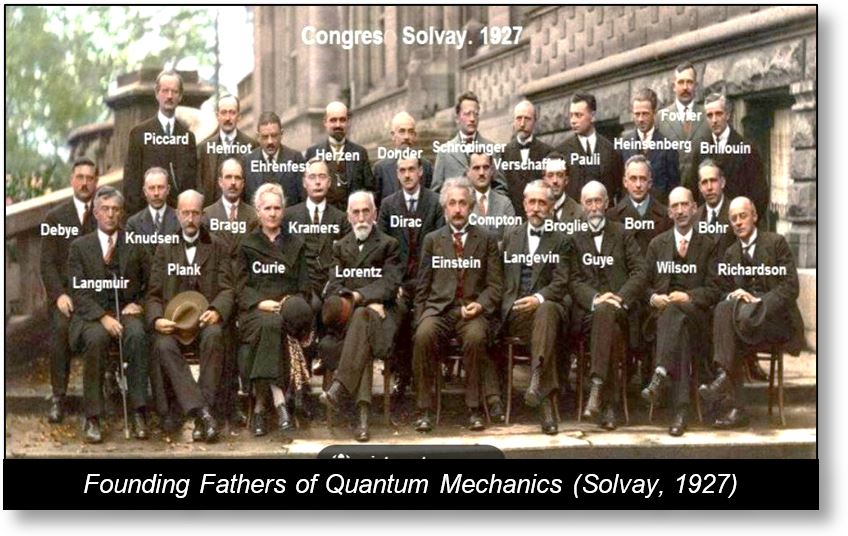

A group of pioneering physicists — including Niels Bohr (Nobel Prize, 1922), Erwin Schrödinger (1933), Werner Heisenberg (1932), Wolfgang Pauli (1945), Max Born (1954), Albert Einstein, and others — formed what became known as the Copenhagen School. These scientists regularly convened at the Solvay Congresses in Belgium, beginning in 1911.

This group maintained that the electron was a particle, or corpuscle. One of the central postulates of the emerging theory of quantum mechanics stated: “The probability of locating a particle is described by its wave function.” As a result, the electron continued to be treated conceptually as a particle. This interpretation became so deeply ingrained that it still appears in many quantum mechanics textbooks today.

Yet this view is flawed. The particle-based definition is misleading, and the probabilistic interpretation itself is open to challenge. An alternative explanation, far more interesting, exists.

As previously discussed, the Spacetime Model treats the electron within the atom not as a moving particle, but as a static, motionless wave. In the following section, we will attempt to clarify what is meant by a “motionless wave.”

Electron-Wave

The traditional depiction of electrons orbiting the nucleus — much like planets circling the Sun — is considered obsolete in the context of the "Spacetime Model". Indeed, if electrons were corpuscles, where would the energy come from to keep them spinning endlessly around the nucleus?

As previously discussed, due to the duality, electrons in atoms behave more like stationary waves, meaning waves that do not propagate through space.

While this perspective aligns more closely with observed phenomena, the exact nature of these motionless waves remains imprecise. Broadly speaking, two conceptual variants can be distinguished:

- Dynamic standing waves, which oscillate continuously. These resemble the vibrations of a guitar string, with nodes and antinodes. However, such oscillations require a constant energy source. Just as guitar strings do not vibrate spontaneously, these waves would need an external input to sustain their motion. This raises a fundamental question: Where does the energy come from to maintain perpetual oscillation in the quantum realm? Could this imply a form of perpetual motion within quantum mechanics?

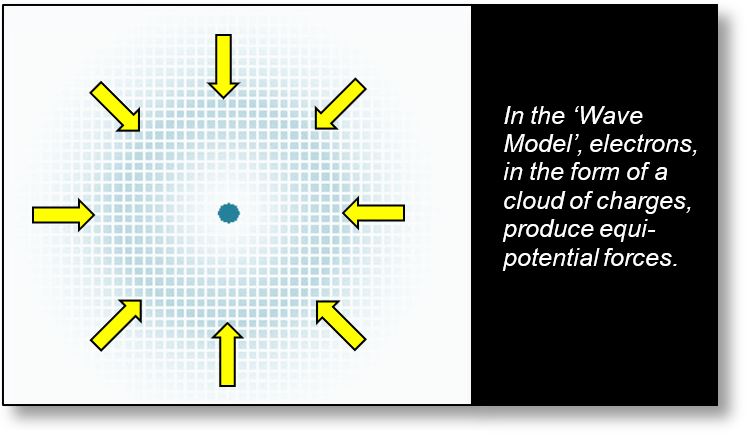

- Static waves, which resemble clouds of stationary charge. In this interpretation, the term “wave” may be somewhat misleading, as the configuration is entirely static — nothing moves. The advantage of this model is that it does not require any energy input to persist.

The Spacetime Model adopts the second interpretation: a static waveform. This approach resolves the issue of perpetual vibration by proposing a configuration that remains stable without external energy, offering a coherent alternative to traditional quantum descriptions.

Bohr Model – Electronic Shells

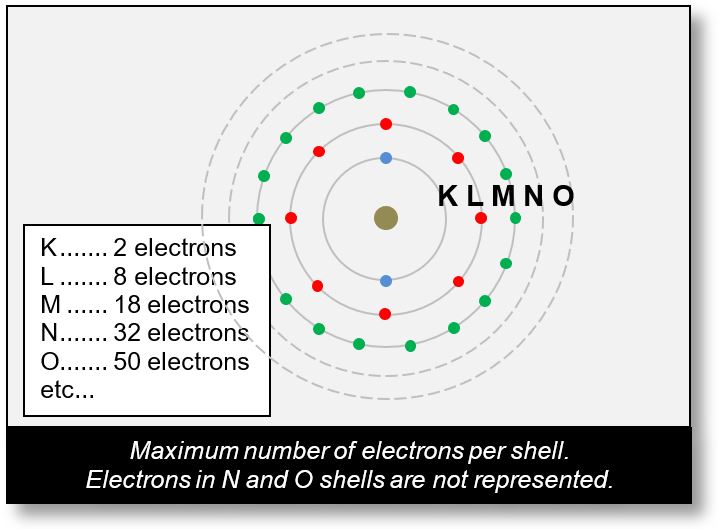

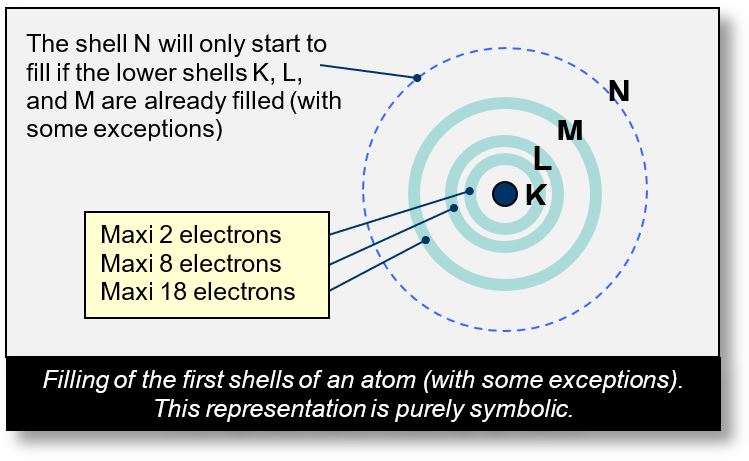

In the Bohr model, orbitals are grouped into concentric shells, labeled as follows:

- K for the first shell,

- L for the second,

- M, N, O, P, etc., for subsequent shells.

Although the use of letters (K, L, M...) to designate electron shells remains widespread, it is now largely outdated. Modern notation favors numerical labels based on the principal quantum number: n = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5...

Each shell has a maximum capacity for electrons.

- The first shell can hold up to 2 electrons,

- The second up to 8,

- The third up to 18, and so on.

Where do these numbers come from? The calculation is simple: The maximum number of electrons in a shell is given by the formula 2 × n2, where n is the shell number. For example:

- The third shell (n = 3) can hold up to 2 × 32 = 18 electrons.

- The fourth shell (n = 4) can hold up to 2 × 42 = 32 electrons.

- The fifth shell (n = 5) can hold up to 2 × 52 = 50 electrons, and so forth.

To fully understand the origin of these limits, one must delve into the details of Schrödinger’s equation.

Let’s consider an electron in the third shell, labeled M. This electron cannot move to the second shell (L) since that shell is already full. However, in practice, some shells may not be filled to their theoretical maximum — there are exceptions.

Example: A carbon atom has 12 electrons, distributed as follows:

- 2 electrons in the first shell (K),

- 8 electrons in the second shell (L),

- 2 electrons in the third shell (M).

Although the third shell can accommodate up to 18 electrons, it contains only 2. This leaves 16 unoccupied positions, often referred to as holes.

Orbitals are not circular paths; rather, they resemble entangled ellipses or complex spatial patterns. Moreover, electrons are not tiny corpuscles as often depicted — they are better described as clouds of charge. An interesting piece of evidence is that Schrödinger’s equation is a wave equation, not a particle equation, which reinforces our wave model theory.

The Schrödinger Model

The Schrödinger equation offers mathematical solutions that define these orbitals. It represents a major breakthrough in atomic theory. However, it does not provide a rational, intuitive explanation — independent of mathematics — for why electrons appear to follow specific paths or "rails" known as orbitals.

If electrons are treated as particles, the existence of these orbital "rails" becomes a genuine mystery. This paradox is explored further below.

The Pauli Exclusion Principle

Quantum mechanics presents many intriguing phenomena — one of which is the Pauli exclusion principle, proposed by Wolfgang Pauli (Nobel Prize, 1945). This principle concerns a property called spin, but we’ll introduce it through a simple analogy.

Imagine satellites orbiting the Earth, each painted either white, blue, or green. According to Pauli’s principle, no two satellites of the same color can occupy the same orbit. This metaphor helps illustrate a key quantum rule: in an atom, no two electrons with identical quantum characteristics can share the same orbital path.

In quantum mechanics, this means that two electrons with the same spin and energy state cannot coexist within the same shell or subshell. But why is this restriction necessary? Interestingly, current quantum theory does not offer a fully rational explanation. It remains one of the foundational postulates — accepted because it works, not because it’s intuitively understood.

Schrödinger’s equation, which calculates orbital levels using subshells (s, p, d, f), does not account for the Pauli principle either. It describes where electrons can be, but not why they must be distinct.

The Pauli exclusion principle is essential for understanding atomic structure, but its application extends beyond atoms. It is also used to describe behavior within atomic nuclei. However, whether this rule still applies at the level of quarks — inside protons and neutrons — remains an open question.

Explanation of the Pauli Exclusion Principle

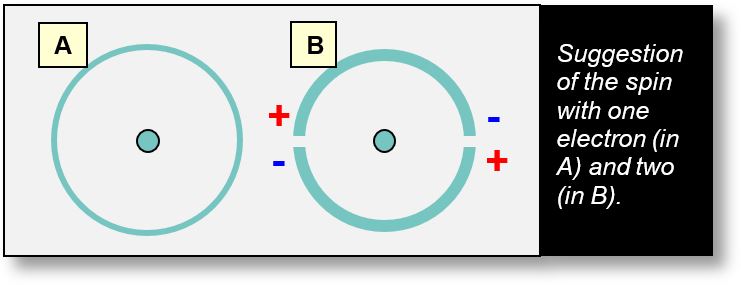

To understand the Pauli exclusion principle, we must move beyond the corpuscular view of the electron and instead reason in terms of static waveforms, as illustrated in the figure below. In this model, electrons are distributed as charge clouds across several discrete zones, consistent with our proposed “wave model.”

When only one electron is present, no conflict arises. However, with two electrons, it becomes possible for them to interact at their extremities, forming the first shell — designated 'K'. Subsequent shells follow the same principle.

This approach may also offer insight into the structure of orbitals — specifically, why the number of electrons per shell increases with distance from the nucleus. As the shell diameter grows, so does its capacity to accommodate electrons. Although this hypothesis aligns with our earlier interpretation of spin, it remains to be experimentally validated.

The figure below illustrates a simple case: an atom where the K shell contains one electron (in configuration A) and two electrons (in configuration B).

Quantized Orbitals

Unlike artificial satellites, which can be placed in any orbit at any altitude, electrons in quantum mechanics are subject to strict constraints. As we've seen, everything is finely calibrated: electrons cannot occupy just any position. Their orbitals are precisely defined by quantum numbers n = 1, n = 2, n = 3, and so on. These orbitals are said to be quantized or discrete1, meaning that only specific energy levels are permitted.

Why are orbitals discrete rather than continuous? We’ll explore a possible explanation using the example below.

Note 1: There is frequent confusion between the terms discrete and quantized. Here's a clarification. The solutions to the Schrödinger equation are derived from Laguerre and Legendre polynomials, themselves solutions of Gauss’s hypergeometric function. These mathematical entities — known as special functions — are widely used in physics. For instance, the propagation of waves on a drum membrane involves Bessel polynomials. Yet, we do not claim that the drum membrane is quantized in the sense of Max Planck’s quantum theory. The situation in quantum mechanics is analogous: the concepts of discrete and quantum should not be conflated. The term quantum refers to systems that operate using quanta — discrete packets of energy. In contrast, discrete often arises from the mathematical structure of solutions, such as the polynomial constraints in the Schrödinger equation. These discrete values emerge from boundary conditions and orthogonality requirements, not necessarily from quantum postulates.

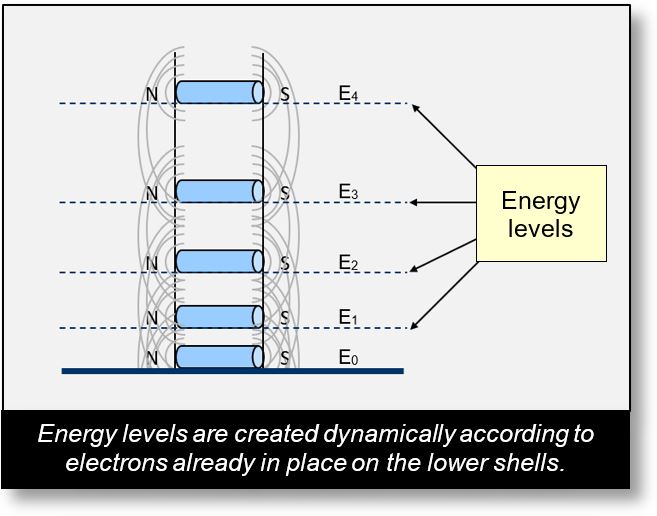

Example: Magnets on Rails

The figure below shows five magnets placed along a vertical rail, all oriented in the same direction. Each magnet is subjected to two forces:

- Gravitational force, which pulls it downward toward the Earth

- Repulsive force from the neighboring magnets, due to their identical orientation

The lower magnets bear the cumulative weight of the magnets above them. As a result, the spacing between magnets is not uniform.

Energy levels — labeled E1, E2, E3, and so on — are formed dynamically as the rail is filled.

If we repeat the experiment under identical conditions, we consistently observe the same spacing pattern: E1, E2, E3... This might suggest that the magnets occupy quantized positions. However, this is not the case. There is nothing inherently quantum about the arrangement of magnets. Their placement follows classical mechanical logic.

Moreover, if we alter the magnetic strength of just one magnet, the entire distribution of spacings changes. This demonstrates that the energy levels E1, E2, E3... are not fixed or predefined — and certainly not quantized in the quantum mechanical sense.

The E1, E2, E3 levels may appear quantized,

but they are not. These levels are formed

dynamically as the rail becomes filled.

Explanation of Orbitals

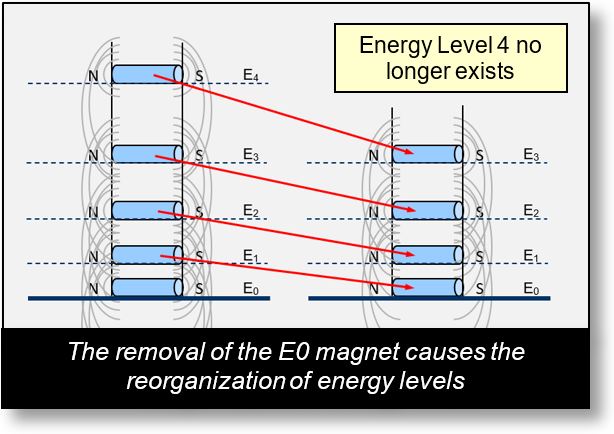

The “rails” mentioned earlier do not actually exist within the atom. Orbitals are formed dynamically, as illustrated in the previous example. The position of the initial electrons determines where the subsequent electrons will be located.

In the figure below, when the E0 magnet is removed, the E1 magnet shifts downward to take its place, becoming the new E0. The other magnets also move down one level accordingly.

Atomic energy levels follow the same principle. When an electron is removed from a shell, the remaining electrons reorganize, and eventually, the other shells adjust as well. An electron from a higher shell may descend to fill the vacancy left behind. However, there are exceptions — such as the aluminum atom.

In summary, the various shells are neither predefined nor inherently quantized, contrary to common belief. The position of new electrons is determined by those already present. There is no mystery here — everything follows a perfectly logical pattern.

Recapitulation

Energy levels are built dynamically, one after another. Electrons naturally settle into orbitals where the electromagnetic force is most favorable. Because these levels form progressively, electrons first occupy the lowest available shells.

In short, if low-level orbitals are absent, higher-level orbitals cannot exist — though there are exceptions1.

The magnetic field associated with these levels can be altered by external disturbances, leading to slight modifications in the orbitals. This phenomenon is known as the Zeeman effect, awarded the Nobel Prize in 1902.

The Zeeman effect shows that orbitals are not permanently quantized; they can be reshaped by local magnetic conditions2.

1/ There are several exceptions — for instance, when orbitals are widely spaced. Sometimes, the “p” and “s” shells overlap, forming hybrid “sp” orbitals. Halo atoms also illustrate such anomalies.

2/ Ultimately, the Zeeman effect, rooted in magnetism, reveals that orbitals are not fixed once and for all. This magnetic influence suggests that spin, like orbitals, may also arise from magnetic interactions — possibly linked to sCells.

Energy Level E0

There remains a fundamental mystery about the atom. As we know, the electron carries a negative charge, while the nucleus is positively charged. The two should attract each other via Coulomb’s force. So why doesn’t the electron simply collapse into the nucleus?

Moreover, if the electron were orbiting the nucleus like a planet, it would emit electromagnetic radiation due to its rotating acceleration — resulting in a continuous loss of energy.

However, according to our Wave Model, the electron is not a point particle in motion but a distributed wave, spread across several sCells located along the orbitals. This distribution generates balanced forces that prevent the electron, in its wave form, from being pulled into the nucleus.

Additionally, the energy loss associated with electromagnetic radiation does not occur in the Wave Model, since orbitals are not paths of motion but rather clouds of static charge.

Puzzle of the Schrödinger Equation

Schrödinger’s equation presents yet another intriguing paradox. Its solutions suggest that the probability of finding an electron is highest at the center of the nucleus — as if the electron were located inside the nucleus rather than orbiting around it... That's odd.

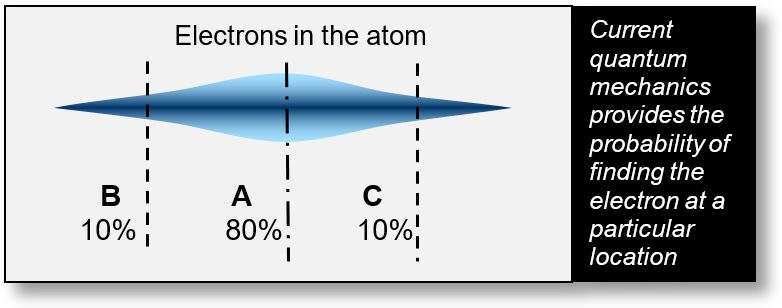

The figure below illustrates this issue. Even today, it is commonly accepted that Schrödinger’s equation describes the probability of locating an electron at a specific place and time.

However, within the Wave Model, this paradox disappears — because the concept of probability itself disappears too. In the figure, the blue cloud represents a probability distribution. For example, it might suggest: “There is an 80% chance of finding the electron at point A, in the center of the atom.” Yet logically, the probability at the nucleus should be zero. This contradiction highlights a limitation of the probabilistic interpretation.

In contrast, the Spacetime Model interprets Schrödinger’s equation not as a probability function, but as a representation of a cloud of electric charges — a static distribution rather than a dynamic likelihood. Since the charge cloud — the electrons — surrounds the nucleus, we have just as much chance of finding electrons along the axis of the nucleus as we do at its periphery.

For Physicists. Einstein opposed the probabilistic interpretation promoted by the Copenhagen School. To his colleague Heisenberg, he famously remarked: “The physicist must study a world that he did not create himself.” Chemists later seized upon this statement, accusing physicists of shaping nature to fit their mathematical models rather than striving to understand its fundamental laws. This criticism is not unfounded.

Indeed, mathematics allows us to express virtually anything — an idea Schrödinger illustrated with his famous thought experiment: a cat that is simultaneously dead and alive. Such paradoxes highlight the limitations of the probabilistic interpretation, which often diverges from the tangible reality of nature. It is, in essence, a construct of mathematics rather than a reflection of physical truth.

Summary Concerning Atoms

The atom is a complex subject that cannot be fully explained in just a few pages. Our aim here is to provide some foundational insights by highlighting certain curiosities in quantum mechanics that merit deeper reflection.

Schrödinger’s equation is precise and highly effective, yet it gives rise to several puzzling questions, such as:

- Why are electrons seemingly forced to follow quantized orbitals, as if confined to rails?

- What determines the maximum number of electrons allowed per shell?

- If the electron is a corpuscle, why doesn’t it collapse into the nucleus, given their opposite charges?

- Why doesn’t the electron fall into the nucleus despite continuously losing energy through electromagnetic radiation?

- If the electron is a particle, what is the source of energy that keeps it rotating indefinitely around the nucleus?

- Is it subject to perpetual motion?

- Why does the highest probability of locating the electron appear to be at the center of the atom?

- What is the underlying rationale for Pauli’s exclusion principle?

- What is the origin of these probability-based interpretations, and how do they relate to the actual behavior of nature?

This webpage has proposed possible answers to these quantum mysteries surrounding the atom. These are hypotheses — thought-provoking ideas that invite further reflection and, ultimately, experimental validation.