Nuclear Structure

Unveiling the Secrets

of the Nucleus

This page does not offer a comprehensive study of the atomic nucleus, but instead highlights one of its peculiar features — its binary internal structure — which remains unknown to physicists.

This aspect is crucial, as it supports the WaveModel theory, which posits that the neutron is a composite of a proton and an electron.

Isobars

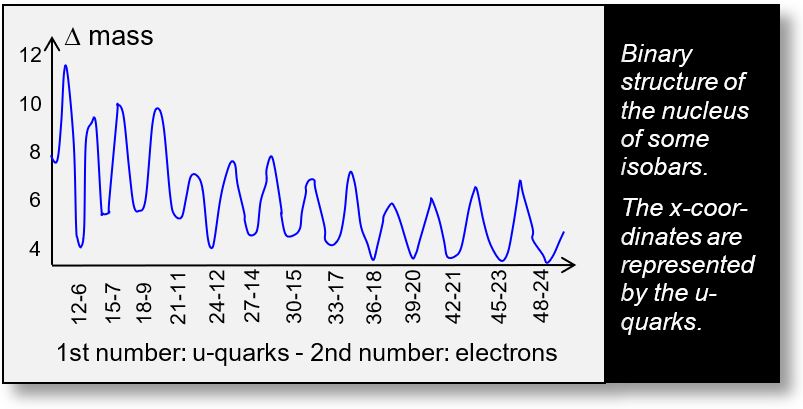

Nuclear graphs are typically plotted using the mass number A, the number of neutrons N, or the atomic number Z. The figure below, however, is based on u-quarks, under the assumption that a d-quark consists of a u-quark surrounded by an electron in its wave form.

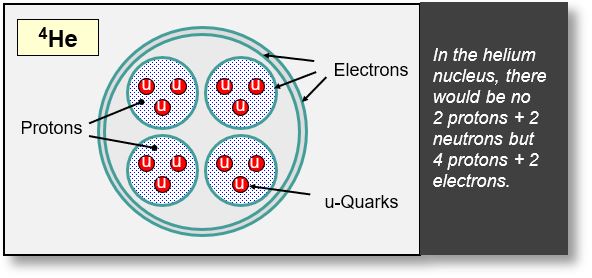

It has been shown that a proton is not composed of two u-quarks and one d-quark, but rather of three u-quarks and one electron. Similarly, each neutron consists of three u-quarks and two electrons.

The figure below illustrates the first nuclei — those with a mass number between 3 and 16. Please refer to the more detailed graphs on the following page for further precision.

The x-axis spans from 12 to 48, reflecting the fact that each nucleon contains three u-quarks. In this model, the neutron transforms into a proton and an electron. The data used are derived from official CODATA values and are considered indisputable.

To enhance readability, the mass of each nucleus has been normalized by its mass number A, and an offset of 930.9 MeV has been subtracted from each value.

The figure has been simplified. A more refined graph identifies the lowest energy point within each isobaric group. This minimum is only achieved when the number of electrons equals half the number of u-quarks, including those associated with the d-quark. This outcome aligns with the result previously found earlier: Ne+ = Ne- = 2A

Nuclei

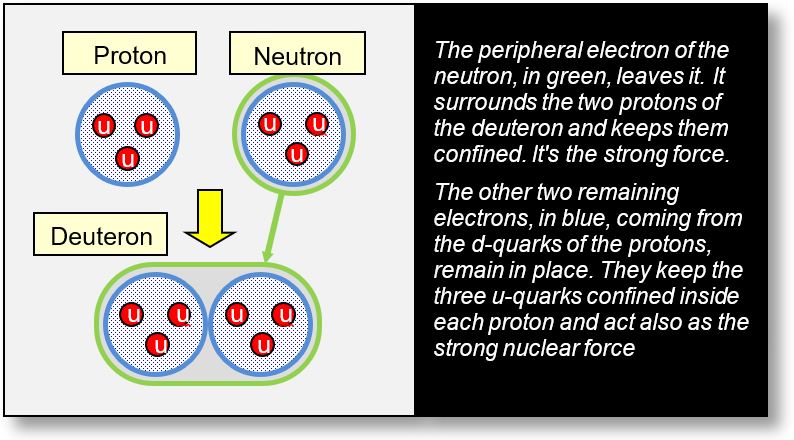

According to our simplified notation, the proton is represented as (u u u)e-, with the electron located at the periphery.

The neutron, by contrast, is written as ((u u u) e-) e-. The difference between the proton and the neutron lies in the additional electron associated with the second d-quark in the neutron. This electron detaches from the d-quark and migrates to the periphery.

Isotopes

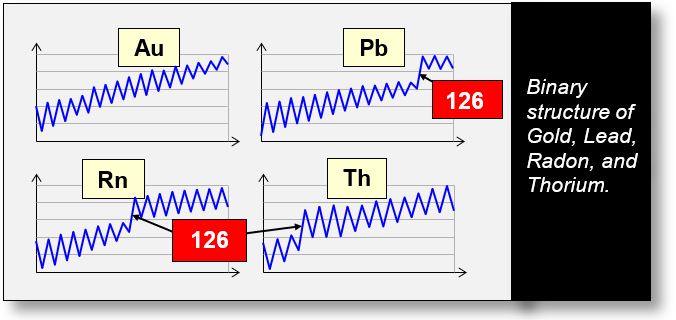

The graphs below, also based on CODATA data, illustrate the composition of a nucleus as the number of neutrons varies. These graphs therefore represent the isotopes of a given chemical element.

On the x-axis, the isotopes are arranged in ascending order, with each point corresponding to the addition of one neutron. The y-axis represents the mass. To better highlight mass variations, the difference between two adjacent isotopes is plotted. This difference, which can be either positive or negative, is equivalent to a derivative: ΔM/ΔN, where M is the mass and N the number of neutrons.

These graphs reveal that the mass of each element oscillates in a binary pattern: a negative derivative is followed by a positive one, and vice versa.

As we can see, a binary phenomenon is occurring within the nucleus. What could be the cause of this binary behavior?

The graphs also show a notable irregularity at N = 126 — the so-called "magic nuclei". These nuclei exhibit zero quadrupole moment, presenting another mystery: their perfectly spherical shape. Why is this the case? Could these nuclei resemble protons structured with concentric u-quarks?

In this webpage, however, we will focus solely on the binary structure of nuclei.

Note: Many studies have explored the atomic nucleus. However, what makes this one particularly compelling is its interpretation, which rests on a novel premise: that the d-quark is composed of a u-quark surrounded by an electron. The figures clearly reveal that the nucleus exhibits a binary internal structure.

These graphs, based on CODATA 2006 data, clearly demonstrate the binary structure of the nucleus.

Structure of the Deuteron

The deuteron is the nucleus of a hydrogen isotope, composed of one proton and one neutron. Before delving into the mystery of its binary structure, it is essential to understand how the deuteron functions (see figure below).

When a neutron encounters a proton, the electron previously associated with the neutron detaches and relocates to the periphery, surrounding both protons. In this model, the deuteron is not composed of a proton and a neutron per se, but rather of two protons and a peripheral electron. This electron plays a critical role: it acts as the agent of the strong nuclear force, confining the two protons within the deuteron structure.

This configuration is more coherent and homogeneous than the conventional proton–neutron model, as it provides a direct mechanism for the strong force. In this framework, the electron itself is responsible for the binding interaction.

Contemporary quantum mechanics, particularly Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD), attempts to explain the strong nuclear force through complex mathematical formulations, yet without definitive conclusions.

In contrast, the reality may be far simpler. Peripheral electrons — originating from d-quarks — could be the true source of the strong nuclear force. We will revisit this hypothesis in a later section.

Binary Structure of the Nucleus

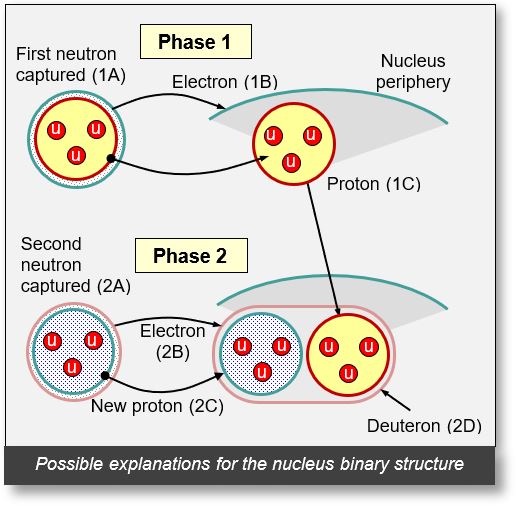

The only plausible explanation for the binary structure of the nucleus is to consider that it is composed of deuterons (see the figure below).

The binary oscillations observed in the previous graphs suggest that two distinct phases are required to form the nuclei of the isotopes in question.

- Phase 1

- Point 1A: The base nucleus captures a neutron, thereby becoming an isotope.

- Point 1B: The electron associated with the neutron detaches and migrates to the periphery of the nucleus. This enhances the strong nuclear force and increases the nucleus's volume.

- Point 1C: With the loss of its peripheral electron, the neutron transforms into a proton.

Result: The increase in the nucleus's closed volume (see Part 1) leads to a corresponding increase in its mass.

- Phase 2

- Point 2A: The nucleus captures a second neutron, forming a new isotope. Recall that this process involves a sequence of neutron captures, i.e., successive isotopes (see previous explanation).

- Point 2B: The peripheral electron (depicted in pink) detaches from the neutron.

- Point 2C: This neutron then becomes a proton (shown in blue).

- Resulting Structure (2D): The electron from point 2B encircles both the newly formed proton (2C) and the proton from phase 1 (1C). The combination — Electron 2B + Proton 1C + Proton 2C — constitutes a deuteron. The mass of the nucleus decreases due to the smaller volume of the deuteron compared to the combined volume of a separate proton and neutron in phase 1.

This cyclical process accounts for the observed binary structure and the sawtooth pattern in the graphs. These two phases repeat in succession, resulting in alternating increases and decreases in nuclear volume within the same isotope group. The earlier figures clearly confirm this behavior.

Validation of the Binary Structure

The graphs above were generated in Excel using official CODATA data, making them easily reproducible on any standard PC. The conclusions are straightforward: the internal structure of the nucleus can only correspond to a configuration based on deuterons. No other arrangement — such as combinations with z=2, z=3, z=4, and so on — produces consistent results.

The binary structure of the deuteron is modeled using our Wave Model. Elements of the Spacetime Model, including aspects of wave–particle duality, are also incorporated. The ‘binary graphs’ early presented were likewise constructed using official data, ensuring their full reliability. This reinforces the credibility of both our Spacetime Model and Wave Model.

The deuteron structure of nuclei, from

CODATA 2006, validates the "Wave Model"

and "Spacetime Model" theories

The Helium Nucleus

We consider the structure of the 4He nucleus to be a fundamental building block of nuclear matter, particularly in heavy nuclei, since alpha particles are themselves helium nuclei.

Several configurations are theoretically possible. However, given the exceptional stability of He-4, the diagram below likely represents the most probable arrangement.

In the figure, a He-4 nucleus is depicted with 6 electrons and 12 u-quarks. These quarks correspond to 8 positrons, based on the principle that 2 positrons are required to generate 3 u-quarks. The resulting electric charge is therefore -6 +8 = +2, which matches the known charge of the He-4 nucleus.

Experimental observations support this configuration, notably through the detection of two electrons in the outer shell of the He-4 nucleus. This aligns with the known properties of alpha particles, which exhibit a particularly strong nuclear force

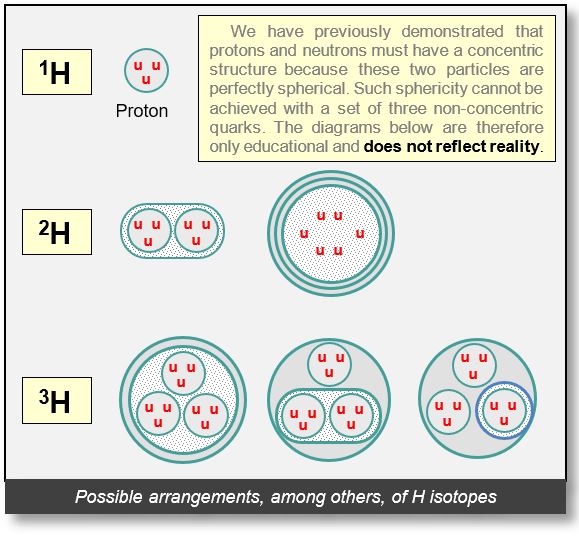

Hydrogen Isotopes

Configurations of hydrogen isotopes are illustrated below. Each particle is consistently surrounded by at least one electron, which is hypothesized to play the role of the strong nuclear force.

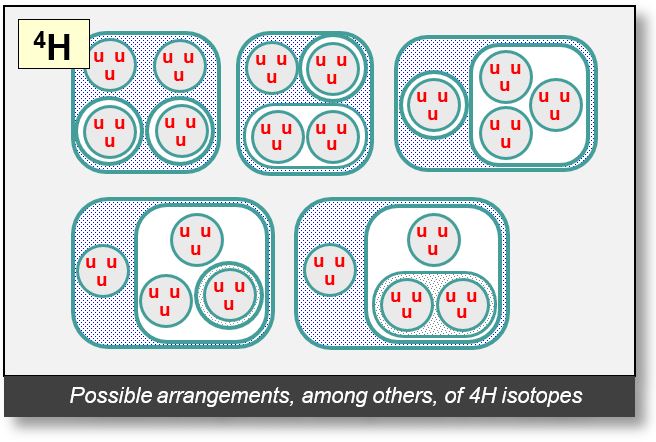

Isotopes of H-4

The figure on the next page presents several possible configurations for the H-4 isotope. In every case, an electron appears in the outer shell, acting as the agent of the strong nuclear force — an essential component of the model.

These diagrams are conceptual proposals. Intuitively, the binary structure of the He-4 nucleus suggests that its protons may transform into deuterons when the nucleus transitions between isotopic states, as discussed earlier.

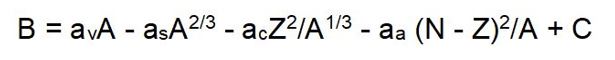

Binding Energy

Binding energy refers to the energy required to hold nucleons together within the atomic nucleus. It can be estimated using the semi-empirical Bethe–Weizsäcker formula, developed by Hans Bethe (Nobel Prize, 1967) and Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker.

The binding energy 𝐸𝑏 of a nucleus with mass 𝑀 is approximately given by the following expression:

Where:

- The first term represents the volume energy (av = 15.56 MeV/c2),

- The second term accounts for the surface energy (as = 17.23 MeV/c2),

- The third term reflects the Coulomb repulsion between protons (ac = 0.7 MeV/c2),

- The fourth term is the asymmetry energy (aa = 23.6 MeV/c2),

- c is an empirical adjustment constant.

Despite its usefulness, this approximation presents certain limitations, which are discussed in the following section.

Surface Energy

The Van der Waals model of a water droplet is often invoked to illustrate surface energy. While this analogy is conceptually interesting, it remains a superficial comparison. In contemporary quantum mechanics, particularly in Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD), which studies quarks and gluons, there is no clear link between binding energy and any so-called "surface force." The inclusion of a surface term in the Bethe–Weizsäcker formula appears arbitrary — perhaps introduced merely to ensure the formula yields correct results.

In contrast, the Spacetime Model offers a coherent explanation: the surface component aligns precisely with our framework. As previously discussed, peripheral electrons act to confine protons and neutrons within the nucleus, functioning like elastic bands that account for the strong nuclear force. Thus, Bethe and Weizsäcker may have unknowingly incorporated a surface term that is difficult to justify within standard quantum mechanics, yet proves essential in the context of the Spacetime Model.

The Coulomb Force

A similar issue arises with the Coulomb term. Given that the Coulomb force is significantly weaker than the strong nuclear force, its role in the Bethe–Weizsäcker formula is questionable and could arguably be omitted.

However, within the Spacetime Model, the strong nuclear force is generated by electrons associated with protons. The nucleus is composed solely of protons — neutrons are excluded. In this context, including a Coulomb term becomes not only logical but necessary. It reflects the electrostatic interactions among protons and complements the electron-mediated confinement mechanism central to the model

Binding Energy and Nuclear Volume

In the Bethe–Weizsäcker formula, both the nuclear volume — specifically the closed volume (see Part 1) — and the binding energy increase with A, the atomic mass number. Physicists traditionally interpret this trend as evidence of nuclear force saturation, based on the assumption that each nucleon interacts only with its immediate neighbors. While this is a plausible hypothesis, the underlying reality may be far simpler.

If we consider the transformation of neutrons into protons within the nucleus, as illustrated by Feynman diagrams, then the atomic number A should be interpreted as the total number of protons, rather than the number of nucleons. The increase in closed volume is likely due to the repulsive Coulomb force acting among these protons. Consequently, it is natural for the volume to grow in proportion to the atomic number.

This is fundamentally a Coulomb problem — not a mysterious saturation effect requiring ad hoc theoretical constructs.

Moreover, the Bethe–Weizsäcker formula does not account for the actual mechanism of the strong nuclear force within the nucleus. According to the Spacetime Model, this force originates from peripheral electrons, which confine protons and neutrons. It is not an intrinsic force within the nucleus itself.

Note: Despite these conceptual limitations, the Bethe–Weizsäcker formula remains a useful approximation for estimating nuclear binding energy.

Summary on the Nucleus

This chapter offers additional insights into the atomic nucleus within the framework of the Wave Model.

As we examine transitions from one isotope to the next, we observe that the progression of neutrons is not linear but occurs in pairs. This alternating pattern — where mass increases and decreases with each step — reveals a binary behavior.

This phenomenon suggests that the nucleus is composed of deuterons.

The discovery of this binary internal structure provides a deeper understanding of nuclear organization. Since the data supporting this observation are derived from CODATA 2006, the binary nature of nuclei is indisputable. It strongly supports the validity of both the Spacetime Model and the Wave Model.