Quarks and Mesons

Understanding Quarks and Mesons

We have already discussed quarks in Part 3. Here, we delve deeper into the topic.

Mesons are elementary particles that arise from various interactions. They exist in multiple forms, but our focus will be limited to the π mesons.

The contents of this webpage are intended as suggestions only. Since the information has not been formally verified, it should be approached with caution.

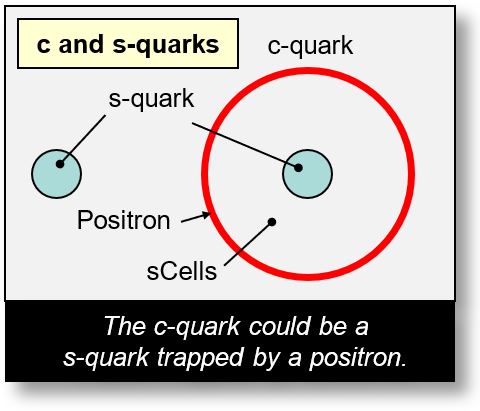

Charm/Strange (c/s) Quarks

In the Wave Model, the charm quark (c-quark) may be conceptualized as a strange quark (s-quark) surrounded by a positron.

Its electric charge increases to +2/3, corresponding to the sum of the s-quark’s charge (−1/3) and the positron’s charge (+1). Simultaneously, the sCells enclosed within the c-quark — positioned between the s-quark and the positron — contribute to its increased mass. This configuration forms a hermetic volume (see Part 1: Mass and Gravitation).

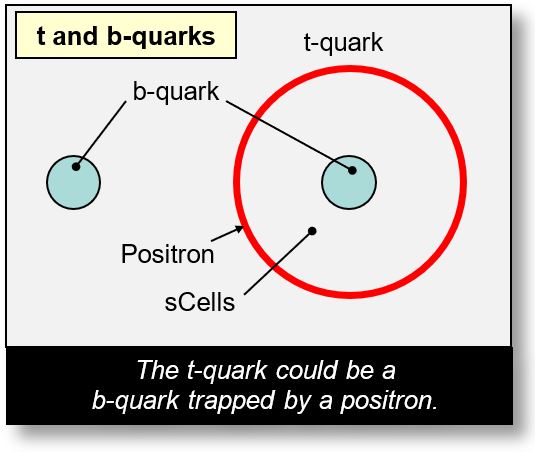

Top/Bottom (t/b) Quarks

The top quark (t-quark), like the charm quark (c-quark), may be conceptualized as a bottom quark (b-quark) surrounded by a positron. Its mass is exceptionally large — approximately 173 GeV. This does not necessarily imply a multitude of components. Rather, such a hermetic volume — and thus such a mass — results from empty sCells that have been confined. Both the t-quark and the c-quark can be considered hermetic volumes.

Given that the b-quark carries a charge of −1/3 and the positron a charge of +1, the resulting charge of the t-quark becomes −1/3 + 1 = +2/3.

The π Mesons

π mesons are among the most well-known composite particles. There are three types of π mesons:

- Neutral π0 Meson: The neutral π0 meson is a subatomic particle belonging to the meson family. It plays a significant role in particle physics and participates in many fundamental interactions. It is composed of two pairs of up and down quarks and antiquarks, which exist in a superposed quantum state. Its mass is approximately 134.97 MeV/c2. The decay modes of the π0 meson are:

- Two gamma photons (98.82% of cases)

- One gamma photon and an electron–positron pair (1.18% of cases)

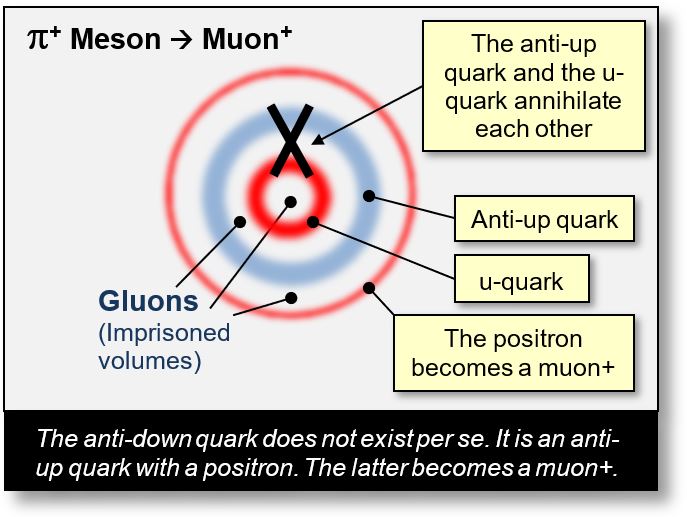

- Charged π+ Meson: The π+ meson consists of an up quark and an anti-down quark. Its mass is approximately 139.57 MeV/c2. Its primary decay mode produces a positive muon (i.e., an anti-muon) in 99.99% of cases.

Within the framework of the Spacetime Model, the anti-down quark is considered to be a composite of an anti-up quark and a positron. The total charge of the π+ meson is therefore:

anti-up quark (−2/3) + positron (+1) + up quark (+2/3) = +1

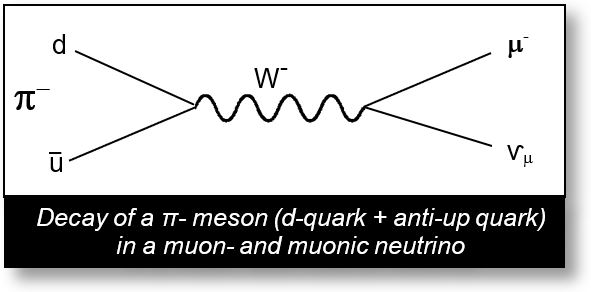

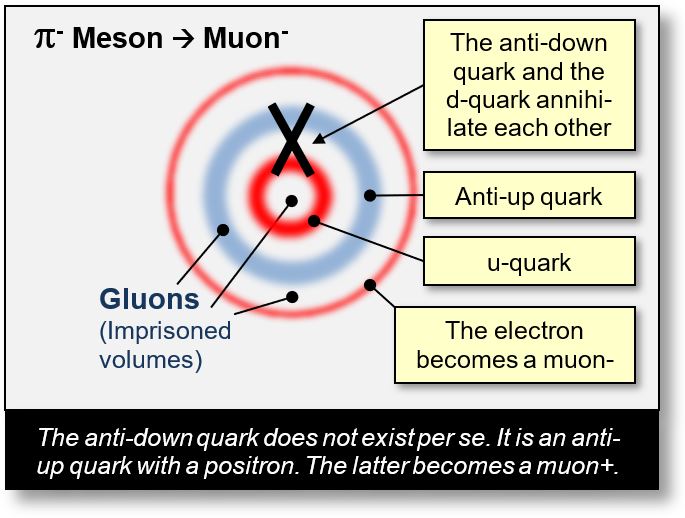

- Charged π- Meson: The π⁻ meson is composed of a down quark (d-quark) and an anti-up quark. Its mass is identical to that of the π+ meson, approximately 139.57 MeV/c². Its primary decay produces a negative muon (μ+) in 99.99% of cases. Within the framework of the Spacetime Model, the d-quark is considered to be a composite of an up quark and an electron. The total charge of the π- meson is therefore:

up quark (+2/3) + electron (−1) + anti-up quark (−2/3) = −1

The Superposition of States: The superposition of states refers to the phenomenon in which a quantum system can exist in multiple states simultaneously. This concept was entirely fabricated to solve certain puzzles in contemporary quantum mechanics.

The Spacetime Model does not adopt this theory. Our interpretations of these phenomena are, in our view, simpler and more rational than the “official” explanations. For instance, consider wave–particle duality (see Part 2), the Young’s slits experiment (see Part 4), or the infamous Schrödinger’s Cat paradox. The idea of a cat being both alive and dead at the same time is, to us, nonsensical.

For this reason, this website does not examine the 'theory of superposition of states' — commonly invoked in the context of mesons — as we consider it to lack a rational foundation.

Muons

The decay of π mesons, as previously discussed, produces either a muon or two gamma photons. Notably, the confined volume (interpreted here as mass) of the mesons is close to that of the muon: approximately 135–139 MeV/c2 for the mesons, and 105 MeV/c2 for the muon. The explanation is straightforward.

During the decay of a π meson, the stability of its constituent quarks is disrupted. Quark–antiquark pairs, along with the electron and positron associated with the π meson, are annihilated (refer to the figures above).

In the case of a neutral π0 meson, its four quarks — even if in a superposed state — mutually annihilate. This process generates an empty volume, which becomes confined by the electron or positron originating from the antiquarks. This confinement leads to the formation of a hermetic volume, which acquires mass (refer to Part 1).

Following the decay, what remains is an electron or positron derived from the down and anti-down quarks. These residual particles correspond to a muon or anti-muon.

Muons possess slightly less mass than the original π mesons, due to the absence of the two or four quark/antiquark components that were present in the mesons.

Note: This conceptual framework is generic and may be adapted to describe other particles.

Sphericity of the Meson

We previously addressed this issue, but return to it here because the π meson contains four quarks. With four quarks, achieving a perfectly spherical configuration is theoretically impossible. The same challenge arises with the three quarks found in protons and neutrons.

The mass of the neutral π meson is remarkably precise: 134.9766 MeV/c2. Such precision suggests that the π meson, like the proton or neutron, exhibits perfect spherical symmetry — an assumption illustrated in the preceding figures.

The internal structure of the π meson resembles that of nucleons, as described earlier. In both mesons and nucleons, quarks are arranged in concentric shells. There is no viable alternative to this configuration.

Mesons must be structured in concentric shells,

as is the case for protons and neutrons, since no

alternative arrangement is possible.

This interpretation may be subject to criticism, yet it remains the only plausible explanation for the observed sphericity of nucleons and mesons.

Overview of Mesons and Muons

This webpage offers further information about quarks and mesons. The Spacetime Model and the Wave Model are fully consistent with the decay of the π meson into a muon.

The charged π meson has a mass of 139.57018 MeV/c², while the muon has a slightly lower mass of approximately 105 MeV/c². This mass difference arises from the number and nature of the constituent quarks.

We have chosen the examples of muons and charged π mesons to illustrate how spacetime, electrons, positrons, and sCells interact and harmonize to form complex particles.

Concentricity of Quarks and Gluons: The study of mesons also reveals intriguing aspects of their internal structure. The precise mass of the π meson suggests that its two or four quarks cannot generate a perfectly spherical particle. As mentioned earlier, the four quarks within the π meson must be arranged concentrically.

This concentric configuration appears to be a structural necessity, just as it is for nucleons, ensuring the stability and symmetry observed in these particles.