Radioactivity

Unveiling the Origins of Radioactivity

Despite the advances of quantum mechanics, some questions about radioactivity remain unresolved. For instance, the origin of the electron in β- decay is still unclear, given that neither the proton (u u d) nor the neutron (u d d) is thought to contain one.

In this chapter, we attempt to address these questions concerning the origin of radioactivity, within the framework of the Spacetime Model.

It should be noted that this chapter focuses solely on the fundamental principle of radioactivity. It does not cover the dynamics of the associated force known as the ‘electroweak force’, nor the ‘W/Z theory’. The neutrino is also excluded from the scope of this discussion.

Origins of Radioactivity

Let us begin by acknowledging the groundbreaking work of Marie Curie on radium and polonium — work that earned her two Nobel Prizes: in Physics (1903) and Chemistry (1911).

Radioactivity arises from spacetime dynamics within the atomic nucleus. When the nucleus becomes unstable, these internal spacetime movements disrupt existing structures such as deuterons, alpha particles, or other composite formations.

This disruption leads to the emission of various particles, including electrons, positrons, alpha particles, and gamma rays. Some gamma rays are emitted simultaneously with other particles.

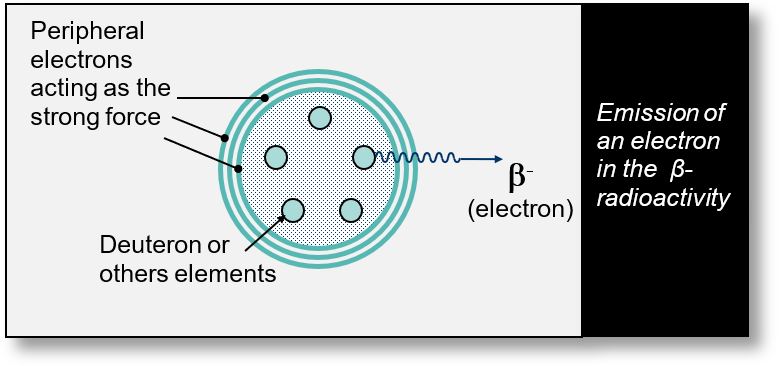

These particles originate from confined volumes — hermetic structures maintained within the nucleus by peripheral electrons or positrons (see Part 1).

These closed volumes, whether fermions or bosons, appear to possess mass. In fact, it is the emptiness within these volumes that contributes to the perceived increase in mass (see Part 1: 'hermetic volumes').

As previously discussed, quarks, leptons, bosons, and waves are all composed of spacetime. It is therefore not surprising to observe an elementary particle such as the W boson (see further) transforming into an electron or another particle (see Part 2) — a phenomenon consistent with the principles of wave–particle duality.

β- Radioactivity (Beta Minus)

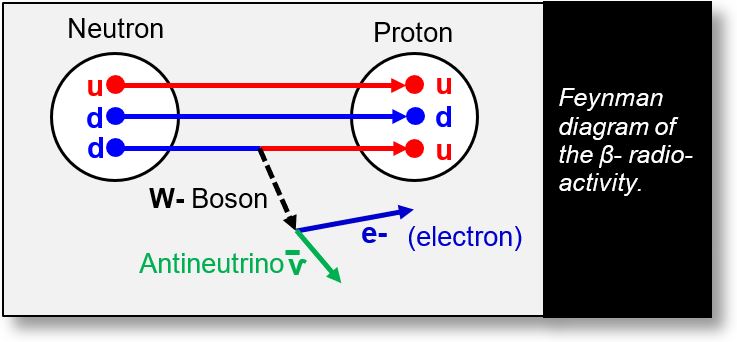

β- radioactivity refers to the emission of an electron from the nucleus. In this process, an excess of neutrons within the nucleus leads to the spontaneous transformation of one neutron into a proton. This transformation is illustrated in the Feynman diagram below.

Question: Where does the emitted electron come from? As previously noted, the d-quark can be viewed as a u-quark with an electron at its periphery. Given that the Feynman diagram accurately represents the process, the electron associated with one of the neutron’s d-quarks gives rise to an intermediate particle known as the W- boson.

Since all particles are composed of spacetime, the W- boson subsequently transforms into the emitted electron.

On the Origin of the Emitted Electron

In physics, spontaneous creation does not occur as it might be imagined in other domains. Electrons emitted outward must originate from somewhere. Whether we name the intermediate particle W⁻ boson, X, Y, or Z, the issue remains unchanged: the electron does not appear out of nowhere.

The emitted electron therefore has a source — and that source is one of the d-quarks within a neutron.

As previously discussed, the mass of the W- boson, approximately 80.434 GeV/c2, corresponds to a closed volume. If this volume undergoes a spatial transformation, its mass is accordingly altered. In this respect, the W- boson shares notable similarities with gluons. Within the framework of the Spacetime Model, the designation may vary (W boson ↔ gluon), but the intrinsic nature remains the same: a particle composed of spacetime, as demonstrated in Part 2 of this website.

The W- boson is conventionally considered the carrier of the electroweak force. However, this force is essentially a modified electromagnetic force. The electrons surrounding the nucleus attenuate the electromagnetic field, giving rise to what is perceived as the electroweak interaction. This concept will be explored further in the next page.

In summary, the electron emitted during β- radioactivity originates from one of the d-quarks of a neutron within the nucleus, via the intermediary of a W- boson.

β+ Radioactivity (beta+)

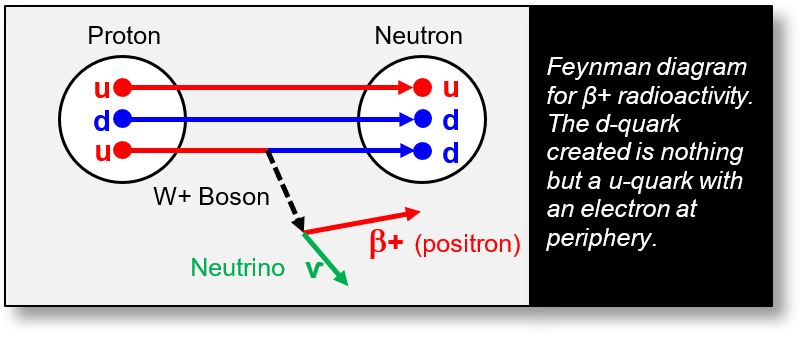

β+ radioactivity involves the emission of a positron. In this process, a proton transforms into a neutron, a positron, and a neutrino. The positron is emitted from the nucleus.

The Feynman diagram below illustrates a u-quark converting into a d-quark via the emission of a W⁺ boson. This W+ boson subsequently decays into a positron and a neutrino. However, as with β- radioactivity, the fundamental question remains: where does this positron originate? The following is one possible explanation.

As previously noted, a gamma ray passing near a nucleus can decay into an electron–positron pair, provided its energy is sufficiently high. The only way for such a gamma ray to interact more intimately with the nucleus is to penetrate it. If an electromagnetic wave possesses enough energy to traverse the nuclear volume, it can generate electron–positron pairs, potentially initiating β⁺ radioactivity. The gamma ray may originate either externally or internally within the nucleus.

In this scenario, the positron is produced inside the nucleus. The accompanying electron contributes to the transformation of a u-quark into a d-quark, thereby facilitating the conversion of a proton into a neutron.

The electron resulting from the gamma interaction is immediately used to bind protons into pairs — forming deuterons or other nuclear configurations. The positron, on the other hand, is expelled either via a W+ boson or possibly through quantum tunneling across the peripheral electron cloud (a hypothesis under investigation).

While alternative mechanisms may exist, this model offers a coherent and experimentally consistent explanation of β+ radioactivity.

α Radioactivity (Alpha Decay)

Alpha radioactivity refers to the emission of a helium nucleus — commonly called an alpha particle — from within an atomic nucleus. This type of decay affects only heavy elements. The helium nucleus consists of two protons and two neutrons, totaling four nucleons. Its mass number is therefore 4.

When a heavy element emits an alpha particle, its mass number decreases by 4. This reduction can be observed in the graph of radioactive filiation presented in our book.

These decay chains are documented on various scientific websites and are also reflected in Mendeleev’s periodic classification of elements, commonly known as the periodic table.

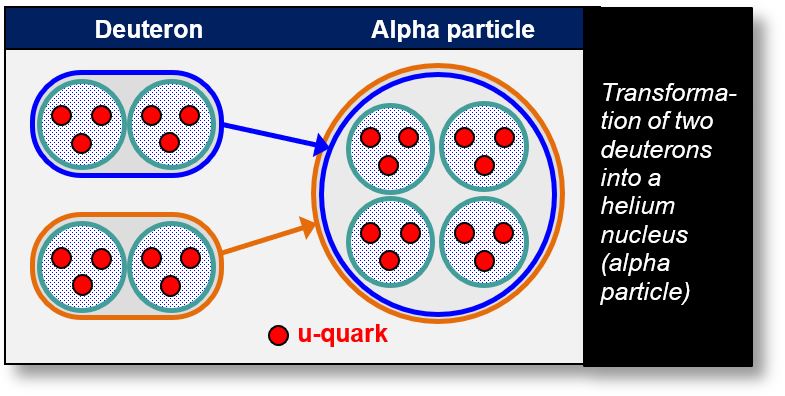

The internal structure of the nucleus suggests two possible origins for alpha particles:

- Preformed alpha particles: They may already exist within the nucleus, composed of u-quarks or electrons. While this is not impossible, it is considered unlikely, as the previous chapter emphasized a binary nuclear structure rather than a quaternary one.

- Formation from deuterons: Alpha particles may result from the association of two deuterons. This binary configuration is illustrated in the figure below.

Finally, it is worth noting that the alpha particle is enveloped by two electrons rather than just one. This dual-electron shell contributes to its enhanced stability and robustness.

γ Radioactivity (Gamma Decay)

A gamma ray is a highly energetic form of electromagnetic radiation. Although gamma rays are more penetrating than α or β particles, they are less ionizing.

Gamma emission can result from a variety of nuclear interactions. While analyzing the energy of emitted gamma rays can yield valuable insights, it is often insufficient to determine their exact origin. Indeed, gamma rays of identical energy may arise from fundamentally different processes.

Gamma rays are frequently emitted in conjunction with other forms of radioactivity, such as α decay. They may also originate from cosmic sources.

It is worth noting that the emission of a gamma ray is often accompanied by the creation of a neutrino or an antineutrino, depending on the specific interaction involved.

Electron Capture

Electron capture is a unique form of radioactivity in which no particles are emitted externally. Instead, an inner-shell electron is absorbed by the nucleus.

Once captured, the electron contributes in one of two ways: it may reinforce the nuclear structure by enhancing the binding forces around the nucleus, or it may facilitate the fusion of two protons into a deuteron or another composite nucleus.

An Overview of Radioactivity

Contemporary quantum mechanics provides an accurate description of all known radioactive phenomena. However, the exact mechanisms occurring within the atomic nucleus remain elusive. In particular, the true origin of the electron or positron emitted during β- or β+ decay is still not fully understood.

Numerous hypotheses have been proposed, yet a comprehensive and fundamental explanation is still lacking.

Building on the concepts introduced in the preceding sections, this chapter seeks to address these unresolved questions about the nucleus, within the framework of the Spacetime Model and the Wave Model.